It’s another custom-tailored post, this time holiday-themed. Once again special thanks to MVP (Most Valuable Patron) Nicc for making this possible – I’m incredibly grateful for your support!

This time around Nicc asked me to write about New Year (Oshougatsu) in Japan. And it’s a topic of considerable weight, because in many ways the two big winter holidays – New Year and Christmas – are flipped from what they represent in the West (especially the U.S.). Japan is not a Christian nation (only 3% of the population) and the holiday holds little spiritual significance (I say this in full acknowledgement of the over-commercialization of Christmas in the West). Christmas is not a day off work (it is a day off school, but only because the New Year’s break has started).

To distill it down to the main point, Christmas is not a family holiday in Japan. The main traditions here are goofy displays in stores (OK, that’s the same), “light-ups”, hooking up, and KFC for dinner. Christmas is mainly a couples holiday here, hugely popular for “first times”. It’s expected that serious couples will have romantic date nights. Teenagers will often have Christmas parties. Gaudy displays of lights at malls and parks are popular night out destinations. And, because of a hugely successful marketing campaign by PepsiCo decades ago, most Japanese are firmly convinced that every (and I do mean every) American eats KFC for Christmas dinner. As such if you want KFC on Christmas here (and I don’t know why you would) you have to reserve weeks in advance.

All the solemnity and family togetherness we associate with Christmas in the West is actually attached to New Year’s in Japan. And most of the partying and drinking we assign to New Year’s actually happens on Christmas. New Year’s isn’t a religious holiday in the strictest sense – it doesn’t even follow the Japanese calendar (it’s been observed on January 1 only since Japan adopted the Gregorian calendar in 1873) – but it’s become a quasi-religious holiday with both Buddhist and Shinto traditions observed. It’s probably second only to the summer’s Obon as a Buddhist holiday, and the country basically shuts down from January 1st-3rd (and for a lot of smaller businesses, even longer).

There are records of Oshougatsu going back for a very long time – as far as the 6th Century in fact. This timing is suggestive of it being a Buddhist festival (this was around the time Buddhism was introduced to Japan from Korea), and it would have been celebrated on whatever date was dictated by the Chinese lunar calendar. But as with almost everything associated with Buddhism in Japan, over the centuries it’s been co-mingled so completely with Shinto that it can be hard to tell where one stops and the other begins.

In fact Japan still celebrates Koshougatsu – effectively “Little New Year” as opposed to “Big New Year” (Oshougatsu) – at the traditional time on the calendar. That would be around mid-February, at the time of the first full moon of the new year (in an agricultural society, a pretty important milestone). As opposed to the “main” holiday, Little New Year is very much as it historically has been – a harvest festival. As such it’s centered around Shinto rituals and shrine visits. In parts of the country where agriculture is basically non-existent (like Tokyo) you’ll often see shrines hold a special Koushougatsu ceremony on January 15.

With New Year’s being such a big deal in Japan, you’d expect anime to be loaded with New Year’s episodes – and you’d be right. Interestingly though, when I sat down and tried to think of some that really stood out in my mind it was harder than I expected (in fact, more manga came to mind than anime). There are plenty of well-known series that have plowed this trough – Lucky Star, Kimi ni Todoke, et al – but for me the ones there are three that stand out. Cross Game (Kou making toshokoshi soba for Aoba and Momiji) is one. Another is Hyouka, where Eru and Houtarou get into an interesting dilemma at her family’s shrine during Hatsumode. And finally Shirokuma Cafe, which had a memorable New Year’s Eve and New Year’s episode back to back.

Here are a few of the more important traditions attached to the celebration of New Year in modern Japan:

- Joya no Kane: The ritual ringing of a temple bell 108 times at (roughly) Midnight on New Year’s Eve. The 108 reflects the number of desires we struggle with in the mortal realm in Buddhist tradition. Historically many temples have allowed visitors to ring the bell on New Year’s Eve (I’ve done so myself), but the pandemic has mostly put that on the shelf.

- Hatsumode: The first shrine or temple visit of the new year, a ritual most Japanese take extremely seriously. Traditionally it’s done during the fist three days of the year, and many do so just after Midnight on New Year’s Eve. As such you’ll find huge lines and crowds at popular shrines (yes, even now). The most popular shrines will effectively turn this event into a matsuri, with food vendors and amazake on offer. Some locations, like Sensou-ji in Tokyo and Fushimi Inari in Kyoto, will receive about 3 million visitors in the first three days of the year.

- Kouhaku Uta Gassen: The “NHK Red and White Song Battle” has been a New Year’s Eve tradition since 1951, and even the young generation still seems hooked. It’s the most-watched TV program in Japan every year. The “Red” team consists of female vocalists, the “White” team of male vocalists, all drawn from the ranks of Japanese popular culture trendy and traditional. Enka singers, J-Pop bands, idol groups – all are staples, few would ever say no to an invite, and for an up and coming performer a booking on Kouhaku can make their career. At the end of the night the winner is determined by a vote by the audience and a panel of judges (the White team has won 39 of the 72 contests to date).

- Decorations: You’ll see them on homes and storefronts all over Japan during the New Year’s period. Kadomatsu, Shimenawa, Kagami – each has a symbolic meaning (as usual), generally tied to Shinto or Buddhism (as usual).

- Osechi: In simplest terms, this is the traditional food for Japanese New Year. But of course, nothing is ever really simple where “traditional” and “Japanese” are involved. So, naturally, there are symbolic attachments to everything that goes into the juubako (the special bento for Osechi), most of which date back to the Heian Period. These can get very specific depending on what the eater is wishing for in the new year – for example, kazunoko (herring roe) for those wanting children, since kazu means “number” and ko means “child”. In practical terms osechi is convenient, since most supermarkets are closed for 2-3 days around the holiday.

- A subset of this category is toshikoshi soba, traditionally eaten on New Year’s Eve. This ritual is a Johnny come lately (Edo Period), the idea being that you let go of the hardships of the prior year because soba noodles are easy to bite through while eating.

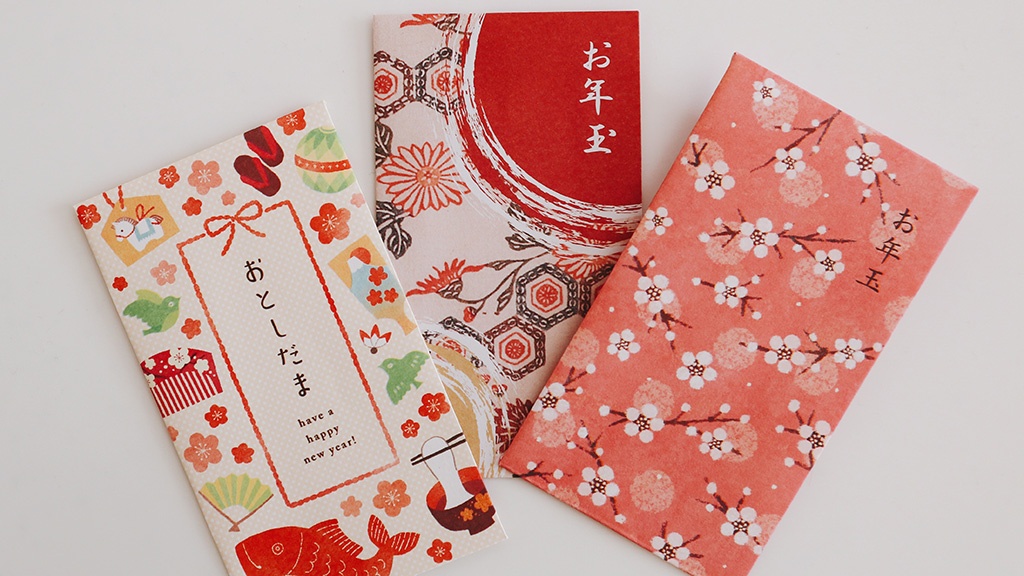

- Otoshidama: The most important tradition to most under 18, this is the gifting of “New Year’s Money” to children. This one seems to have originated from the very old tradition of gifting toshidama (small rice cakes) to the visiting New Year’s deity. Eventually this transferred to parents giving them to children, then over time rice cakes were replaced by cash (in a very particular otoshidama envelope). Generally kids will get them from very close older relatives and possibly close family friends, they average around ¥5000, and often continue into the college years. Also, you’re not supposed to open the envelope in front of other people (for reasons which seem pretty logical to me).

- Nengajo: Americans generally send Christmas cards (unsurprisingly). For the Japanese, it’s all about New Year’s cards. And like so much with social relationships here, getting it wrong carries the risk of grave offense. Who should get them (a lot of people is the short answer) is the first question. What does one say? Nengajo are so important that Japan Post guarantees delivery on New Year’s Day (they deliver 365 days a year) if they’re postmarked between December 15-25. The overwhelming majority of Nengajo these days are pre-stamped postcards with the postage included. And that’s something like two billion of them (about 15 for every person in Japan). This is yet another ritual that originally hails from the Heian (greetings for those you’re unable to meet face to face). Their use has been declining in the internet age (though it’s ticked back up with the pandemic) but New Year’s cards remain extremely popular and important.

- Fukubukuro: “Lucky bags” are a relatively modern New Year’s tradition (maybe early 20th Century) but have nevertheless become quite popular. The idea is simple – you’re buying blind, with the guarantee that the contents will be worth more than what you pay. Everybody from the neighborhood bakery to huge chain stores and online retailers offer them around the holiday, and they can range from a hundred Yen to tens of millions. The key is to research who you’re buying from, and thus improve the odds you’ll get something you actually want.

- Bounenkai/Shinnenkai: Anyone with even a passing knowledge of Japan has probably heard of the nomikai, the legendary (infamous) Japanese drinking party. Those are generally work-related and like every other social ritual in Japan involve a Byzantine set of unspoken rules about how to behave (such as if you don’t act drunk you’re considered to be rude, for not enjoying yourself). Bounenkai and Shinnenkai are the year-end versions – the first being the end of year version in December, the second the welcoming of the new year in January. Again office parties are the most common take but they can be held by students too (under-20’s generally – though not always – abstain from alcohol), or even circles of friends. And yes, they usually involve a prodigious amount of drinking (or pretending to drink and acting drunk).

All in all, the New Year’s period is a fascinating part of the Japanese calendar, and along with Obon the most important of the year in many respects. It’s Japan at its most singular, a chance for many of its unique traditions to assert their influence over a weary populace. It’s certainly fun to observe as an outsider, but even more so if you throw yourself into the ritual as best you can and try and embrace the strange.

geha714

December 16, 2022 at 7:58 pmExcellent article, Enzo!

Guardian Enzo

December 16, 2022 at 9:18 pmThank you!

Aera

December 17, 2022 at 12:39 pmI’ve been really enjoying your articles that bring up about the Chrysantemum taboo and this too! It’s a lot of fun to read more about the Japanese culture and history. Thank you very much for writing this up!

Guardian Enzo

December 17, 2022 at 4:22 pmYou’re very welcome. Thank Nicc too – he sponsored both posts!

Riv

December 18, 2022 at 4:53 amVery interesting! The thing about the KFC is so fascinating.

Guardian Enzo

December 18, 2022 at 10:36 amA brilliant marketing campaign exploiting a country’s rather shocking ignorance about other cultures to make the entire populace believe an abject lie for financial gain.

Nicc

December 18, 2022 at 9:52 pmI really enjoyed reading this and I learned a lot of new things about New Year’s in Japan. I was thinking about bringing up KFC in a different topic, but this was added in nicely. Indeed, behold the power of marketing. Japanese cuisine has no shortage of fried foods (A show I watch on a regular basis is “Dining with the Chef” on NHK World. There are a lot of recipes involving frying), but somehow Christmas means eating the Colonel’s fried chicken. He even looks similar to Santa. I’d rather have the karaage, though.

I also always found it interesting that it followed the Gregorian Calendar, while adopting the Chinese zodiac. The only difference between the two pig vs wild boar. The Year of the Rabbit will be coming soon, and later on in the lunar calendar. At January 22nd, it’s a tad earlier than usual. I’ll have to dig my red-colored articles again.

The New Year’s episode is a staple in anime along with the beach episode and the summer festival episode. As I pointed out before, it’s also a great excuse for the artists to dress up their characters in kimonos. As for especially memorable episodes, it’s difficult for me to think of one. One that I can think which was an important one at least is from “Fruits Basket” when Yuki and Ryo stay with Tohru over New Years.

Kouhaku sounds like it’s a hoot to watch and maybe I’ll get a feed to watch somehow. Oh yeah, osechi. The Japanese grocery stores around here sell those. I ought to try one someday, even if they seem a tad expensive. The New Year cards, right! I’ve seen them in the Japanese grocery stores too and in the Daiso stores in the area. I always liked the designs on those cards. The red packets have long been a familiar sight for me. I’ve seen the lucky bags brought up several times in anime and manga.

Thank you again for this very informative write-up and I have a greater understanding of the holiday and its traditions now.

Guardian Enzo

December 19, 2022 at 6:28 amNicc, I should be the one doing the thanking here. You are indeed a MVP!

Nicc

December 20, 2022 at 2:02 pmYou are very welcome and I’ve got some more topics in mind for 2023.