As animanga fans, our minds certainly go straight to Japan when he hear the word “honorific”. But of course they’re a worldwide phenomenon in almost every culture – mister, monsieur, herr, signore, et al. We tend to take such things for granted in our own culture but taking English as an example, communication would feel very strange to most of us if honorifics suddenly disappeared. We take little note of their presence, but would be immediately struck by their absence.

Nevertheless, it’s fair to say that honorifics play an outsized role in the Japanese language. In English we have our everyday honorifics such as “mister, miss” etc.. And professional honorifics, such as referring to judges as “Your Honor” and special forms of address for doctors, professors and the like. In countries with a hereditary nobility you have another layer – “majesty”, highness”, “lord”, “Your Grace”. Japan has those too of course, but the difference for me lies in this fact: as with so much of the Japanese language, groups are critical. You’re a part of one, or you’re not – and honorifics are used to reinforce this fact.

Another area where the peculiarity of Japanese culture asserts itself through honorifics is in that most intimate of groups, the family. In the West we certainly have our share of family honorifics – fathers alone could be “Dad”, “Pops”, “Papa”, “Daddy”, “Da”, “Pap”, and myriad others. But typically, whatever honorific the kids apply to him, to his wife he’s “Bob” (or whatever). Spouses usually call each other by their first names, as do siblings (you do hear “sis” and “bro”, “honey” and “dear”, but first names are the default). The focus is on the identity of the individual.

In Japan – and I think this is very revealing – the focus is on the role, not the individual. Once a husband and wife have a child, they are “Otou-san” and “Okaa-san” – not just to the child, but to each other (and their own parents). Once a second child is born, the eldest becomes Onee-san, Onii-san, etc… Of course in Japan there are many variations on these family honorifics, but the point is that the individual’s given name is virtually never used in the family once the relationships have been established by birth, except for the youngest child (in itself a way of reinforcing their lower status in the family). It even applies to second generations – once the first grandchild arrives the elders become Obaa-san and Oji-san to each other, to their kids, and to their grandchildren.

Japanese honorific speech (keigo – 敬語) is a huge topic – far too huge for a neophyte like me to cover in this space. Broadly speaking it can be broken down into three classes:

- Teineigo (丁寧語), or everyday keigo. This is what we commonly think of as “polite speech” in Japanese, used with people one is not intimately familiar with.

- Sonkeigo (尊敬語), used as a means of expressing respect to those who outrank one socially (such as teachers and bosses).

- Kenjougo (謙譲語), basically humble speech. In using kenjougo one lowers themselves below the position of the listener (it’s used when apologizing, for example).

Now, the reality is much, much more complicated – to call that a simplification is an understatement. But for a non-Japanese person for whom the Byzantine complexities of keigo would take a lifetime to understand, it’s a useful starting point.

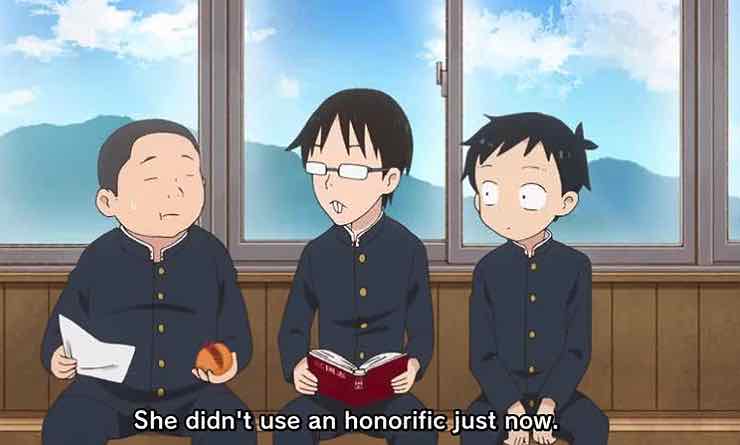

Interestingly, it’s not known exactly when or how honorifics in the modern sense first entered into the Japanese language, though they were certainly in use at least as far back as the Heian Period. They weren’t really codified in writing until the 17th Century. Within the confines of the three categories above, there are seemingly limitless variations, some of which will be known to anime and manga fans. “-san”, is of course the most neutral and widely-used – as close as you’re going to get in Japanese to a Mr/Mrs/Ms kind of thing. If you don’t know which one to use, this is the safest to default to (and not using an honorific at all is as big a faux pas as using the wrong one in many circumstances).

Leveling up, we have “-sama”. This is a term of respect for those older or with higher status. As an example, a member of the royal family. However, when the Emperor’s sister married a commoner, she lost the right to be -sama in the press, and became a -san.

“-kun” is one fans will know well. Most famously it’s used to refer to boys, but it can be used by any older or senior to their junior at work or school (including, adults, and including females). In my experience, however, -kun is rarely used to address schoolboys in classroom settings – all students typically get referred to as -san by their teachers, especially from middle school up.

“-chan” is another broadly famous example. It can be a term of affection for a close friend, it can refer to a child, it can be used (carefully) to refer to women one knows well, and it’s often used in reference to animals or anything cute. It’s also sometimes used for even older relatives – as in “nee-chan” or “otou-chan”.

“-dono” is, like -sama, a term of respect. But it has a more archaic air to it. It literally means something like “My Lord/Lady” and it often used as such. In samurai anime and manga this is the one you’ll typically hear being used as a term of respect.

Then we have the miscellaneous bucket – stuff like -tan (even cuter than -chan) and -bo (exclusively for boys, especially of the “little scamp” variety).

The truth is, I could go on about this subject for pages and barely scratch the surface – it’s complicated. But as Nicc specifically asked me to address the various forms of address we hear so often in anime – for brothers, sisters, parents – I’m going to jump straight to that. Let’s take for example “older brother/sister”, which alone has a dizzying array of options (though almost never using the actual given name).

- Onii-san (Onee-san) seems to be as close to a generic, polite address as there is. It can also be used when referring to or addressing someone else’s older sibling, or even an older person (especially older kid) irrespective of sibling status. I think it would be fair to say that “Nii-san”, “Onii-chan”, ‘Niichan” et al are variations on this address rather than distinct honorifics. Perhaps more childish, certainly more familiar, but riffs on the same melody.

- Ani (Ane) – This is roughly the same politeness level, but more formal (and please note that politeness and formality are distinct measures). Seems to be most commonly used when talking about your older sibling to someone outside your family.

- Aniue (Aneue) is an honorific that will be very familiar to animanga fans, especially those of period pieces. The “ue” part literally means “above”, so the entire phrase carries a meaning of great respect. One might imagine from anime that it’s still used by rich ojousans and bocchans (interesting honorifics in themselves), but I gather that it’s almost entirely a historical relic at this point.

- Aniki (“aneki” exists too, but seems pretty rarely used) is another animanga standard, and among my favorites. You hear yakuza types use it, bozu like Jim Hawking use it, and it was originally – like aniue – a samurai term. But over time aniki has become more casual, and is frequently used as a friendly way or showing respect to older mentors or colleagues who aren’t your actual brother (though it can be used there too). In fact you sometimes hear “aniki” used with older female figures as well as male in those sorts of situations.

Let’s take a look at parents, with no less dizzying an array of options:

- Okaasan (Otousan) is the default address in this relationship. It likewise is considered the proper honorific to use when referring to someone else’s parent. The same form of address is used for mothers/fathers in-law, but the Kanji is different (because Japanese).

- Haha (Chichi) is a humble way of referring to your parent when talking to someone outside your family. Don’t use it when talking about someone else’s parent though – stick with the above.

- Kaachan/Okaachan (Touchan/Otouchan) are the Japanese equivalent of “Mama/Papa”. They’re somewhat childish in nature, but older children and adults might still use them when addressing their parents as a show of affection.

- Hahaue (Chichiue) – see “Aniue” above. Old-fashioned, ceremonial, carries a whiff of samurai or nobility. Likewise unlikely to be heard much these days even among rich kids, no matter what anime would have you believe.

- Okan (Oton) are Kansai-ben all the way.

- Oyaji is an interesting one – there doesn’t seem to be a maternal variant of this as far as I can tell. It’s another one you hear in anime a lot. In English “(my) old man” probably comes the closest. You can use it to refer to your own dad, but it seems to be quite commonly used to refer generally to older men.

- And of course, let’s not to forget that “Mama” and “Papa” are quite commonly used in Japan as is, especially by children.

Finally, we have a couple of interesting and very important oddballs – ojisan/obasan and ojiisan/obaasan. This is a general term for “uncles/aunts” and “grandpas/grandmas” that aren’t literally those things to the speaker. One “i/a” is broadly for middle-aged people, two for senior citizens – so you have to be extremely careful in choosing which one to use for fear of giving offense (or indeed using one at all, as a person in their 30’s might not appreciate being called an “Ojisan”).

Now, I’ve just barely touched on the whole regional dialect thing with “Okan/Oton”. There are literally dozens if not hundreds of dialectic honorifics in regional Japanese, Kansai-ben being the most famous. We really would be here all day if I tried to cover that topic…

My sincere thanks again to Nicc for stepping up with this commission request – it’s been a blast putting it together!

geha714

May 15, 2023 at 7:55 pmExcellent article, Enzo!

Guardian Enzo

May 15, 2023 at 8:24 pmThank you!

Rob Barrett

May 16, 2023 at 3:52 amThank you, Enzo-san

Nicc

May 18, 2023 at 5:36 amI’ve been looking forward to reading this as it’s a topic that has always interested me. How it started was when I started watching anime in its original language instead of dubbed. At least for the dubs that I watched back in the day, the honorifcs were always omitted. I will say that it makes sense for the intended audience.

That was the start. I dipped my toes in the water and realized there was an ocean beneath. A deep dive and you would have to write a book. This is exactly what I was looking for when I first brought up this topic and it was illuminating to read. I hope that it was helpful to the other readers of the site too and give more understanding to our anime watching or manga/LN reading. Thanks again for taking up this commission.

Guardian Enzo

May 18, 2023 at 6:29 amThank you for sponsoring it! As you said, it was dipping a toe in the ocean, really.