When you have a show that’s great to begin with deliver an episode that exemplifies everything that’s great about it, you know it’s going to be, well, great. Golden Kamuy hasn’t skipped a beat transitioning from its third (and best) season to this one – and to a new studio and director besides. But it always had another gear you know it would shift into sooner or later, and this was the week it happened. As sure as clockwork, whenever Mob Psycho 100 is airing you know there’s going to be a masterpiece-tier series competing with it. Hasn’t failed yet.

Like I said, everything that makes GK so great was in this episode. Absurdist comedy, dick (and ball) jokes, a history lesson, appreciation of the Ainu culture, and some serious personal drama. As it begins we find the Sugimoto party ordered to stay in Toyohara (now Yuzhno-Sakhalinsk, then the capital of Karafuto) and await the arrival of Lt. Tsurumi. That means some downtime, which means time for stuff like comic relief and character exploration. And for characters like Cikapasi – who hadn’t uttered a line of dialogue all season – to finally be a part of the story.

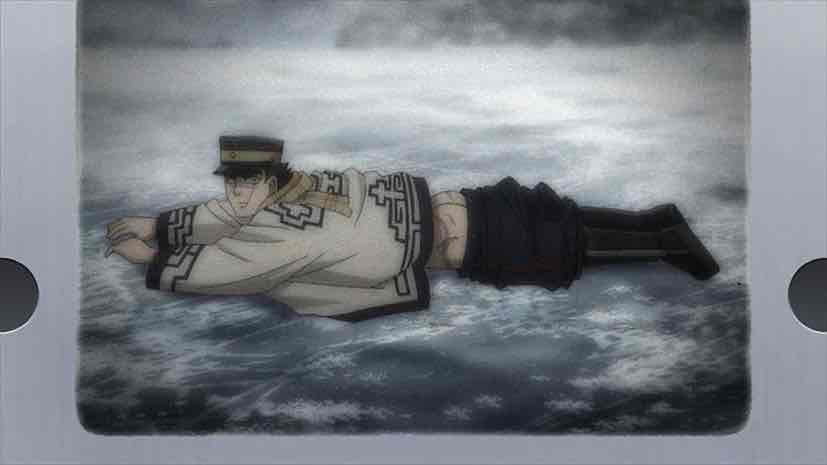

Cikapasi, in fact, is proving useful as a means to allay the suspicions of the local Karafuto Ainu, which he does in part by telling everyone they meet that Tanigaki has giant testicles. Without question a father and son bond has emerged with these two, and Cikapasi clearly still thinks of Inkarmat as a surrogate mother (Tanigaki seems not to be telling the boy the whole truth where she’s concerned). Meanwhile Sugimoto and Asirpa take the opportunity for a hunting trip into the mountains, where they run into two men with an early film camera – the earliest viable one in fact, the cinématographe developed by the Lumière brothers in France.

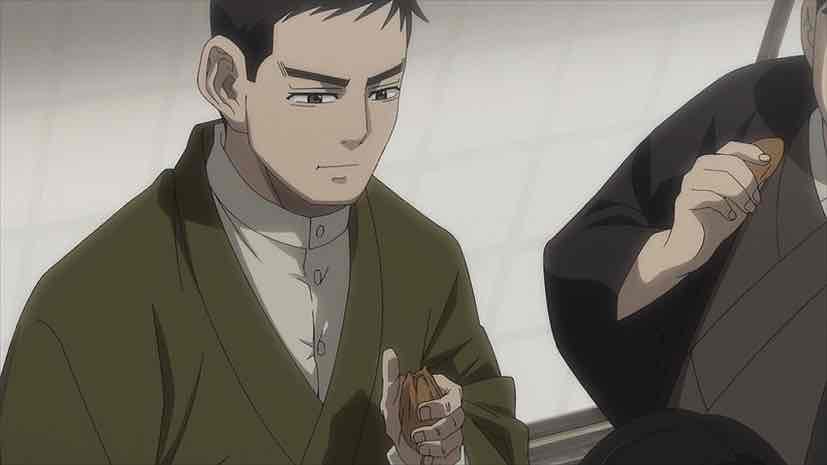

Noda-sensei never makes shit up when he can pull from actual history, and he does so here in the person of Inaba Katsutaro (Imaruoka Atsushi). He’s based on Inabata Katsutaro, who attended school in Lyon with one of the Lumière brothers and was the first man to bring film to Japan. He also brought a Lumière technician named François-Constant Girel and many reels of film to help him drum up interest in his new venture. They’re in the process of filming the local Ainu population, which immediately sparks Asirpa’s interest – though first she and Sugimoto have to save their asses from a pair of psychotic wolverines (though that phrase is redundant I guess).

This is where the comedy part kicks in, and it’s pretty out there – but tinged with bitter reality. Asirpa is smart and perceptive – she understands the danger of her culture disappearing, with both the Russian and Japanese governments openly hostile to its existence. Inaba is reluctant to waste his time (as he sees it) making silent films about a culture with an oral storytelling tradition, but Sugimoto forcefully reminds him of what his and Girel’s fate would have been without Asirpra’s intervention. He reluctantly agrees, and Asirpa instantly morphs into every bad-boy director caricature in pure Golden Kamuy fashion.

Asirpa’s “Panampe and Penampe” stories (all actual Ainu folk tales) are extremely dick-intensive and utterly preposterous, and I couldn’t stop laughing for a moment of them. She then turns to Cikapasi to star in “Kesorap“, a story about three brothers. This one is quite a bit more serious, and it seems to be very pointedly foreshadowing a parting (and even possibly the details of it) for Cikapasi and Tanigaki – who plays his older brother and guardian, who turns out to be a bird Kamuy. I think the story has been hinting in that direction all along but I’d still be quite sad to see it, since Tanigaki and Cikapasi have clearly grown to love each other.

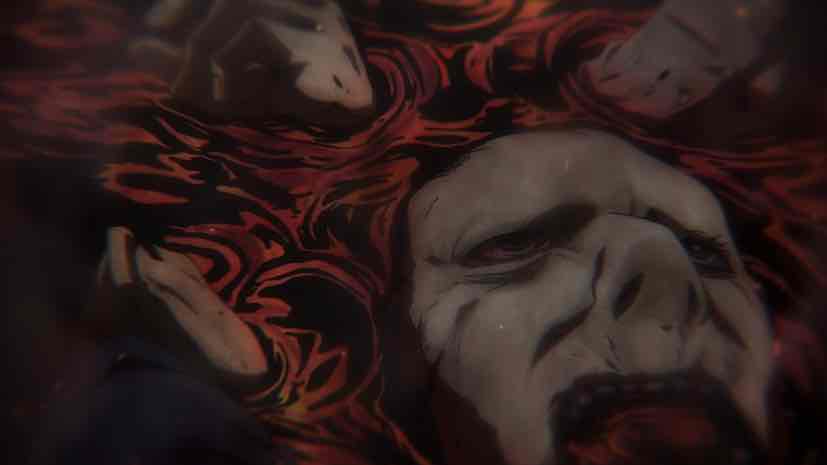

When the gang settles into the local theater to watch the film, though, the kicker is not the films Asirpa shot but one Girel and Inaba took years earlier in Otaru. Girel recognized something in Asirpa’s blue eyes, and indeed that film shows Wilk. And not only Wilk (and Kiroranke, too) but someone we’ve never seen before – Asirpa’s mother, who indeed is the spitting image of her. It’s a miracle in this day and age for Asirpa to actually be able to see her mother – but a short-lived one, as the chemicals in the projector start a fire (ridiculously common with early film technology) and the film is burned to a crisp.

This is painful for Asirpa for obvious and subtle reasons. It’s a further reminder of how fragile knowledge of the customs and traditions of her people is. It hardens her resolve to do whatever she has to in order to protect it. But just as much, it hardens Sugimoto’s resolve to protect her from the dark path Wilk and Kiroranke’s machinations have placed her on. Asirpa is right, Sugimoto is doing this for himself in a sense. But in the same sense that all love is selfish – we’re drawn to love others because we like the way it makes us feel. Sugimoto’s wish for Asirpa – that she leave the race for the gold behind and live her own life for herself – and in direct opposition to what she’s come to believe is her destiny. And this is the conflict that’s sure to drive much of Golden Kamuy’s final act.

Marty

November 2, 2022 at 11:47 pmU know, I’m convinced that the setting of Golden Kamuy was no accident. The turn of the century us certainly a time filled with the natural conflict between the Old world and the new. The Russo-Japanese War also gave plenty of the characters the PTSD that comes with modern warfare without the masa destruction of WWI.

I never would have thought film would be addressed in Golden Kamuy, but I should’ve known better.

Early film is one of my personal fascinations. People like to think Silent film only ranges a brief period between 1915-1927, but they forget there are entire DECADES of technical and artistic Innovation before Chaplin and Valentino became household names.

Film, specially documentary film or home movies, is as close to a time machine as we are going to get. Asirpa’s brief moment of closure with her parents on the screen is not only beautiful, but could ONLY have happened this way on this era, film is a much more íntimate experience than pictures or just stories.