Yeah, you know, I could write page upon page about those episodes. But I really don’t want to do that. First of all 1500-word posts are a lot of damn work (spoiler: I managed to cap it at 1255), and it’s already 10:30 at night. And it’s not like material this good needs a sales pitch from a dude like me (though if I can evangelize it a little, that’s not a bad thing). But my usual scribbled notes are about half a page in my notebook – there’s just so damn much I want to say. That’s what really great storytelling does to me, time after time.

Yeah, you know, I could write page upon page about those episodes. But I really don’t want to do that. First of all 1500-word posts are a lot of damn work (spoiler: I managed to cap it at 1255), and it’s already 10:30 at night. And it’s not like material this good needs a sales pitch from a dude like me (though if I can evangelize it a little, that’s not a bad thing). But my usual scribbled notes are about half a page in my notebook – there’s just so damn much I want to say. That’s what really great storytelling does to me, time after time.

Of all the alchemies of narrative fiction, pathos and humor are a strong contender for the most powerful formula. Kotarou wa Hitorigurashi is labeled as a “comedy”, and for the record, it is damn funny. But the feels are so damn real here, and they’re earned rather than paid for with bribes. Yes, the premise is pretty out there even by manga standards. But – while I won’t claim to know for a fact that such a thing could never happen in Japan – what the series does is use that premise to shed light on more “normal” and universal sorts of pain. It’s almost like a fantasy series in that sense, in that the best fantasies often use the freedom that genre gives them to comment on real life in ways more “realistic” stories usually can’t.

Of all the alchemies of narrative fiction, pathos and humor are a strong contender for the most powerful formula. Kotarou wa Hitorigurashi is labeled as a “comedy”, and for the record, it is damn funny. But the feels are so damn real here, and they’re earned rather than paid for with bribes. Yes, the premise is pretty out there even by manga standards. But – while I won’t claim to know for a fact that such a thing could never happen in Japan – what the series does is use that premise to shed light on more “normal” and universal sorts of pain. It’s almost like a fantasy series in that sense, in that the best fantasies often use the freedom that genre gives them to comment on real life in ways more “realistic” stories usually can’t.

Every one of these episodes’ vignettes (three chapters per week seems to be the default formula) does exactly this – it uses humor to gnaw at the emotional wound that is Kotarou’s life. Kotarou uses increasingly elaborate “disguises” to get extra balloons from the man at the store. Why? Because he plans to have Shin draw faces on them and pretend they’re his family. When the balloon dude finds out exactly what the weird kid’s scam was all about, it hits him like a ton of bricks – a total stranger. Kotarou drafts Tamaru-san to help him shop so he can look cool. Outrageousness follows. But why is Kotarou doing this? Because he’s trying to find a way to get people to like him enough so he won’t be discarded.

Every one of these episodes’ vignettes (three chapters per week seems to be the default formula) does exactly this – it uses humor to gnaw at the emotional wound that is Kotarou’s life. Kotarou uses increasingly elaborate “disguises” to get extra balloons from the man at the store. Why? Because he plans to have Shin draw faces on them and pretend they’re his family. When the balloon dude finds out exactly what the weird kid’s scam was all about, it hits him like a ton of bricks – a total stranger. Kotarou drafts Tamaru-san to help him shop so he can look cool. Outrageousness follows. But why is Kotarou doing this? Because he’s trying to find a way to get people to like him enough so he won’t be discarded.

The other side of that story is the way Tamaru is treated – with suspicion, unsurprisingly in a society as rigidly conformist as Japan. All of Kotarou’s neighbors are kind of “undesirable” in their way – a slacker who doesn’t work in an office and dresses in sweats, a guy who looks like a yakuza (maybe he is, we don’t know), a hostess. Maybe that’s why they’re so open to embracing this weird kid who’s all alone – they know what it’s like to be rejected by peers and probably family.

The other side of that story is the way Tamaru is treated – with suspicion, unsurprisingly in a society as rigidly conformist as Japan. All of Kotarou’s neighbors are kind of “undesirable” in their way – a slacker who doesn’t work in an office and dresses in sweats, a guy who looks like a yakuza (maybe he is, we don’t know), a hostess. Maybe that’s why they’re so open to embracing this weird kid who’s all alone – they know what it’s like to be rejected by peers and probably family.

We also see Kotarou go to Mizuki’s hostess club to “select” her (ouch), because he overhears her puzzling over whether to renew her lease. This is outrageous and funny where it should be too, but again it’s really just another facet of Kotarou’s raging fear of abandonment. And then there’s the photos – Kotarou is deathly afraid of being in them. I kind of pegged this one right away because it just fit so perfectly – there’s someone he doesn’t want to see his face and come after him. I’m assuming this is his father, and he seems like a pretty awful sort. Among the many scars Kotarou bears that seems to be among the ugliest.

We also see Kotarou go to Mizuki’s hostess club to “select” her (ouch), because he overhears her puzzling over whether to renew her lease. This is outrageous and funny where it should be too, but again it’s really just another facet of Kotarou’s raging fear of abandonment. And then there’s the photos – Kotarou is deathly afraid of being in them. I kind of pegged this one right away because it just fit so perfectly – there’s someone he doesn’t want to see his face and come after him. I’m assuming this is his father, and he seems like a pretty awful sort. Among the many scars Kotarou bears that seems to be among the ugliest.

Every chapter in these episodes was a winner for me, but the ones involving Kobayashi-san (Hanamori Yumiri) were the most devastating. She’s a lawyer who’s been handed the duty of delivering Kotarou’s weekly stipend to him. While her sempai tries to prepare her for what to expect, you can’t really prepare someone for that. Indeed, he clearly worries because he follows her to check up on her the first time. Kobayashi-san doesn’t relish this seemingly menial task, thinking it beneath her. But once she’s immersed in it she can’t help but be emotionally invested. Again, I think the point here is that all of these people aren’t exceptional – they’re normal people with a capacity for empathy. And that’s all it takes to want to do the right thing.

Every chapter in these episodes was a winner for me, but the ones involving Kobayashi-san (Hanamori Yumiri) were the most devastating. She’s a lawyer who’s been handed the duty of delivering Kotarou’s weekly stipend to him. While her sempai tries to prepare her for what to expect, you can’t really prepare someone for that. Indeed, he clearly worries because he follows her to check up on her the first time. Kobayashi-san doesn’t relish this seemingly menial task, thinking it beneath her. But once she’s immersed in it she can’t help but be emotionally invested. Again, I think the point here is that all of these people aren’t exceptional – they’re normal people with a capacity for empathy. And that’s all it takes to want to do the right thing.

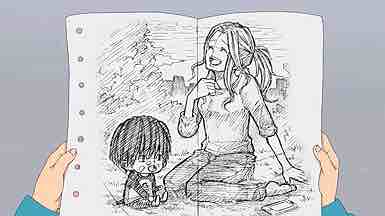

The money is Kotarou’s mother’s life insurance policy, which is a big development for obvious reasons. We don’t know much about her – we know she pretty much ignored her son and now, now we know she’s dead. We don’t know why – if it were suicide I assume the insurance would have been voided – but Kobayashi-san is warned that she must only tell Kotarou “a kind person” donates the money. These people are trying to be kind to Kotarou, and maybe this is a kindness given how young he is. But the worst part for him is he clearly suspects the truth and wants closure – he even gets Kobayashi-san drunk on Karino’s beer (he knows how to pour a perfect glass, hmm) to loosen her tongue, but she manages to get through it (and for what it’s worth, I was reflexively rooting for her to keep the secret).

The money is Kotarou’s mother’s life insurance policy, which is a big development for obvious reasons. We don’t know much about her – we know she pretty much ignored her son and now, now we know she’s dead. We don’t know why – if it were suicide I assume the insurance would have been voided – but Kobayashi-san is warned that she must only tell Kotarou “a kind person” donates the money. These people are trying to be kind to Kotarou, and maybe this is a kindness given how young he is. But the worst part for him is he clearly suspects the truth and wants closure – he even gets Kobayashi-san drunk on Karino’s beer (he knows how to pour a perfect glass, hmm) to loosen her tongue, but she manages to get through it (and for what it’s worth, I was reflexively rooting for her to keep the secret).

The hits just keep on coming. Kotarou’s new friend Kazuya lives in a house with a nanny (who he orders around shamelessly), and Kotarou takes it on himself to teach Kazuya how to be self-sufficient. The whole crayfish thing is pretty funny but again, when you step back and think about a four year-old’s motivation for doing this being what Kotarou’s is, it’s pretty gut-wrenching. We also see Kitarou struggling with dodgeball – he can’t catch, he doesn’t want to throw, and he refuses to dodge because that would be like ignoring the person who threw the ball. The pathos is so thick here you could cut it with a knife – Kotarou bonding with his father figure Shin over sports, and the way his circumstances have forced him to overthink even something as simple as a dodgeball game.

The hits just keep on coming. Kotarou’s new friend Kazuya lives in a house with a nanny (who he orders around shamelessly), and Kotarou takes it on himself to teach Kazuya how to be self-sufficient. The whole crayfish thing is pretty funny but again, when you step back and think about a four year-old’s motivation for doing this being what Kotarou’s is, it’s pretty gut-wrenching. We also see Kitarou struggling with dodgeball – he can’t catch, he doesn’t want to throw, and he refuses to dodge because that would be like ignoring the person who threw the ball. The pathos is so thick here you could cut it with a knife – Kotarou bonding with his father figure Shin over sports, and the way his circumstances have forced him to overthink even something as simple as a dodgeball game.

The last couple of chapters don’t spare the knife. Kotarou’s other friend Takuya runs away from home to make his parents jealous. and drafts Kotarou to join him. Takuya constantly tells Kotarou how jealous he is (“I’m not jealous of myself” is the perfect reply). But when he comes home at night to Kotarou’s place and the truth becomes clear even to his toddler brain, Takuya immediately flees home to give his parents a hug. And then the whole bit with the birthday cake – this close-dances with being maudlin, but somehow avoids it, even with the stray cats. The essence of this chapter is Kotarou not realizing that birthday parties were celebrations, because it never occurs to him that someone would want to celebrate his being born.

The last couple of chapters don’t spare the knife. Kotarou’s other friend Takuya runs away from home to make his parents jealous. and drafts Kotarou to join him. Takuya constantly tells Kotarou how jealous he is (“I’m not jealous of myself” is the perfect reply). But when he comes home at night to Kotarou’s place and the truth becomes clear even to his toddler brain, Takuya immediately flees home to give his parents a hug. And then the whole bit with the birthday cake – this close-dances with being maudlin, but somehow avoids it, even with the stray cats. The essence of this chapter is Kotarou not realizing that birthday parties were celebrations, because it never occurs to him that someone would want to celebrate his being born.

There are still six episodes to go of course (for me). But I think a central theme of Kotaro Lives alone is the question of what responsibility these strangers have for Kotarou. They have lives, they’re not rich – and whatever bad things have happened to Kotarou aren’t their fault. It’s society that’s failed him – and his family too, in some way or another as yet unspecified. They don’t have to do any of this – especially Shin, who’s effectively stepped in as Kotarou’s guardian, especially as far as the school is concerned. They do – but what if they didn’t? What would happen to Kotarou then – and would that make them bad people? I don’t know the answer and I don’t know if Kotarou wa Hitorigurashi will try and offer one, but it’s certainly interesting to consider – perfectly expected of this smart, rather ruthless, and thoroughly superb series.

There are still six episodes to go of course (for me). But I think a central theme of Kotaro Lives alone is the question of what responsibility these strangers have for Kotarou. They have lives, they’re not rich – and whatever bad things have happened to Kotarou aren’t their fault. It’s society that’s failed him – and his family too, in some way or another as yet unspecified. They don’t have to do any of this – especially Shin, who’s effectively stepped in as Kotarou’s guardian, especially as far as the school is concerned. They do – but what if they didn’t? What would happen to Kotarou then – and would that make them bad people? I don’t know the answer and I don’t know if Kotarou wa Hitorigurashi will try and offer one, but it’s certainly interesting to consider – perfectly expected of this smart, rather ruthless, and thoroughly superb series.

DP

March 20, 2022 at 1:13 pmI have no objection to people who like this show, but I feel the need to weigh in with a contrarian opinion.

Personally, almost every vignette in this series (with maybe just a couple of exceptions) seems like little more than bald manipulation. The author thinks of some sort of tear-jerking revelation (e.g., tissue-eating!) and then writes a heavy-handed, schematic sketch to draw out the pathos.

Literally every single named character has some sort of sad backstory that just so happens to dovetail with the protagonist’s own baleful past. If there’s a more simplistic way to construct a story than this, I’m glad I’ve never experienced it!

To me, Kotaro has simply the laziest sort of writing/plotting possible, and I have to say that by the end of these ten episodes I felt like canceling my Netflix subscription.

I know this is a minority opinion, but in case there are other people out there who feel the same way I do, I just want them to know it’s OK to despise this show, as in my opinion, it surely doesn’t think too highly of its audience.

There aren’t many series that make me angry, but this is absolutely one of them.

Guardian Enzo

March 20, 2022 at 3:39 pmIt sure sounds like you have an objection to people liking it…

I don’t think anyone needs your approval to dislike anything, but if it makes you feel any better I think hardly anyone is watching it.

Marty

March 21, 2022 at 9:38 amI hate the fact that a series as good as this one had turned out to be are overlooked. Do u think it’s more the source material or Netflix?

Also, I don’t want to stir up anything, but I find it particularly funny that people will call this “emotionally-manipulative,” but eat up shows like Vivy or Your Lie in April like hotcakes.

Guardian Enzo

March 21, 2022 at 12:19 pmNetflix is the biggest problem IMO – it just doesn’t distribute within the normal anime universe. But I mean, this is hardly a series thematically conducive to being a commercial hit with Western fans anyway.

Rasu

March 22, 2022 at 4:24 amThey even call Violet Evergarden a masterpiece, to me that was indeed shamelessly manipulative and nauseous, same goes for KnY and SnK. Despite me not having the right to categorize people by their likes and dislikes, but unlike this show, I think I can be wary of SnK fans for example, I prefer manipulation for being kinda empathical than manipulation to think massive genocide is ok and a good solution yo complex problema (along with nationalism and fascism), the later are nuts and I rather not be around people that agressive who likes better violence over using their brains; yet, they can like it and damage their own hearts and lungs while blindly imitating it, I don’t care.

Netflix will be ok without a single unsuscription due to one single show (they’ve other guaranteed blucbusters why should they carne?), It’d kinda childish and egoccentric to think that argument serves of sthg.

Yann

March 21, 2022 at 12:28 pmI’m somewhere in between with this series… I do enjoy it and find it overall pretty touching, but it does feel a bit manipulative because of the needed initial suspension of disbelief required to accept the premise. Assuming Kotaro’s predicament is eventually explained, I’ll probably feel differently, but right now the main situation feels contrived. It makes it hard for me to immersed myself in the story and some of the feelings it’s attempting to evoke fall flat because of that.

I still like the show, but I get why some people would not.

Guardian Enzo

March 21, 2022 at 2:08 pmLike I said, for me it plays as a fantasy using fantastical elements to comment on real situations.

Litho

March 21, 2022 at 4:32 pmI kind of agree about the writing being lazy, but saying you’re considering cancelling your subscription over this show and not all the other crap on Netflix that’s orders of magnitudes more lowbrow? Yeah, no. You’ll be subscribed till you’re in a geriatric ward.

Princess Usagi

March 21, 2022 at 10:44 amI love how this show sensitively addresses very real traumas that other series either sidestep or sensationalize. I feel like every episode rips me to pieces and I have to try to gather them up before bingeing the next episode. I find the adults interesting too and I think they’re drawn to Koutaro, partly from sympathy for him, and also partly because he makes them face themselves and their own issues. As to whether not helping him would make them bad, that is challenging-it’s not like they would ignore him out of bad intent. If they ignored him, it wouldn’t make them villainous on the level of Koutaro’s dad, but (at least for me), they would be guilty of indifference. But fortunately, they are kind characters!

Rob Barrett

March 22, 2022 at 6:27 amWell, I did binge the entire season, and it was very dusty in my house that night. Very dusty. I think the dryness of the humor is a good antidote to the more maudlin aspects of the show–the upcoming story about the dentist’s office was, for me, the one “Very Special Episode” of the season.