The only hard part with Chikyuugai Shounen Shoujo for me, honestly, is resisting the temptation to finish it too fast. I wanted to blitz through it last weekend, when I started. I sure as hell wanted to do so here. But my natural instinct with stuff like this is always to savor it (and with stuff like the dentist to make the appointment as soon as possible). That problem would have been avoided with a traditional TV/streaming series, of course. And it would have been longer, too. But then, so far it’s pretty close to perfect (no matter what the aggregator scores say), and I’m not sure it would have looked this amazing without Netflix being involved.

The only hard part with Chikyuugai Shounen Shoujo for me, honestly, is resisting the temptation to finish it too fast. I wanted to blitz through it last weekend, when I started. I sure as hell wanted to do so here. But my natural instinct with stuff like this is always to savor it (and with stuff like the dentist to make the appointment as soon as possible). That problem would have been avoided with a traditional TV/streaming series, of course. And it would have been longer, too. But then, so far it’s pretty close to perfect (no matter what the aggregator scores say), and I’m not sure it would have looked this amazing without Netflix being involved.

The Orbital Children has phased through a couple of different identities in these first four episodes. It’s a coming-of-age story, a comedy, a kid’s adventure, a disaster flick. Most elementally it’s a lost in space series – or at least it was at the start. Now we’re seeing its other core identity come into view, a musing on the future of the human race. This is pretty much classic Iso Mitsuo – he has things that fascinate him, and he uses his anime (rare though they are) to explore them. He did it in Dennou Coil and he’s doing it again here, with some themes that carry over and some that are quite different.

The Orbital Children has phased through a couple of different identities in these first four episodes. It’s a coming-of-age story, a comedy, a kid’s adventure, a disaster flick. Most elementally it’s a lost in space series – or at least it was at the start. Now we’re seeing its other core identity come into view, a musing on the future of the human race. This is pretty much classic Iso Mitsuo – he has things that fascinate him, and he uses his anime (rare though they are) to explore them. He did it in Dennou Coil and he’s doing it again here, with some themes that carry over and some that are quite different.

As well, we’re seeing the adults in the cast take on larger roles here (and indeed, larger than they ever did in Dennou Coil). Most prominent of course is Nasa Houston (who last week I neglected to mention is played by Ise Mariya). There’s also Touya’s uncle, the commander, trying desperately to save his nephew and the civilians in his care even as conditions worsen around him. And the elderly ex-engineer, unceremoniously fired by the new owners of Anshin, who’s been the one inside the mascot outfit this whole time. He’s still got his savvy, but is subject to fits of dementia at inopportune moments.

As well, we’re seeing the adults in the cast take on larger roles here (and indeed, larger than they ever did in Dennou Coil). Most prominent of course is Nasa Houston (who last week I neglected to mention is played by Ise Mariya). There’s also Touya’s uncle, the commander, trying desperately to save his nephew and the civilians in his care even as conditions worsen around him. And the elderly ex-engineer, unceremoniously fired by the new owners of Anshin, who’s been the one inside the mascot outfit this whole time. He’s still got his savvy, but is subject to fits of dementia at inopportune moments.

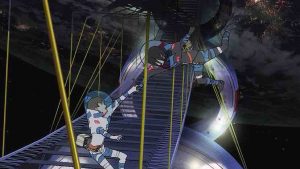

The survival story still packs plenty of urgency, and it’s depicted in tense and visually striking form. With their current location about to run out of air, the first priority is getting to the next module over, which still has power. That means a long EVA on a slender catwalk, without enough real spacesuits to go around. Touya is the natural leader for this moment – even Taiyou thinks so – though Touya is extremely uncomfortable in that role. He and Taiyou have no choice but to make the journey in their “life jacket” ONIQLO suits (and Hiroshi in a “child’s bubble“) because there aren’t enough working spacesuits for everybody. This means risking decompression sickness (the bends) but the only alternative is death (which is much the same reason Mina makes the trip despite declaring it “Muri!” for her).

The survival story still packs plenty of urgency, and it’s depicted in tense and visually striking form. With their current location about to run out of air, the first priority is getting to the next module over, which still has power. That means a long EVA on a slender catwalk, without enough real spacesuits to go around. Touya is the natural leader for this moment – even Taiyou thinks so – though Touya is extremely uncomfortable in that role. He and Taiyou have no choice but to make the journey in their “life jacket” ONIQLO suits (and Hiroshi in a “child’s bubble“) because there aren’t enough working spacesuits for everybody. This means risking decompression sickness (the bends) but the only alternative is death (which is much the same reason Mina makes the trip despite declaring it “Muri!” for her).

The essence of the survival side of things is watching these (mostly) kids try and make-do with whatever they can use on this seemingly ill-maintained, under-equipped station. That means stuff meant for tourists, mostly, but it’s any port in a storm. In the midst of this we see a fascinating bond begin to form between Taiyou and Touya, the two oldest boys in the group. This bond is the bridge to the other main face of Chikyuugai, because these two represent the philosophical poles in opposition in this story. And nowhere is this clash of incompatible worldviews more in evidence than with Seven, the euthanized AI that designed Toiuya and Konoha’s implants.

The essence of the survival side of things is watching these (mostly) kids try and make-do with whatever they can use on this seemingly ill-maintained, under-equipped station. That means stuff meant for tourists, mostly, but it’s any port in a storm. In the midst of this we see a fascinating bond begin to form between Taiyou and Touya, the two oldest boys in the group. This bond is the bridge to the other main face of Chikyuugai, because these two represent the philosophical poles in opposition in this story. And nowhere is this clash of incompatible worldviews more in evidence than with Seven, the euthanized AI that designed Toiuya and Konoha’s implants.

Seven is at the center of both the plot and intellectual undercurrent of The Orbital Children. Taiyou is (as he self-identifies) a black-and-white person. For him Seven was a rogue entity that had to be put down to save humanity, and responsible for Touya’s current suffering. To Touya Seven was the being that gave he and Konoha a chance at life – its solution wasn’t perfect, but for them the alternative was death by age three. Earthers are the ones who took his hope for a future away from him, because they took Seven away from him. Since he’s presumably never spent time with Earthers before this, it’s not surprising that his view of them is pretty black-and-white in its own right. He has no individuals to contrast against his view of the collective (or hadn’t until now).

Seven is at the center of both the plot and intellectual undercurrent of The Orbital Children. Taiyou is (as he self-identifies) a black-and-white person. For him Seven was a rogue entity that had to be put down to save humanity, and responsible for Touya’s current suffering. To Touya Seven was the being that gave he and Konoha a chance at life – its solution wasn’t perfect, but for them the alternative was death by age three. Earthers are the ones who took his hope for a future away from him, because they took Seven away from him. Since he’s presumably never spent time with Earthers before this, it’s not surprising that his view of them is pretty black-and-white in its own right. He has no individuals to contrast against his view of the collective (or hadn’t until now).

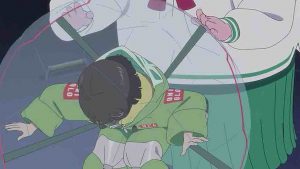

Again, it must be stated that Iso’s depiction of the closed society of children is remarkably convincing. Hiroshi slides into a natural fit as Touya’s disciple, and Touya begins to act uncharacteristically like a big brother. Mina is frankly pretty annoying, but in a rather realistic fashion. She has a role to play here, and as unflattering as it may be it’s basically that of the majority of people and how they go through their lives (superficially). Konoha is mostly a background figure, but her journey towards acceptance of her own seemingly imminent death is quite heartbreaking in an understated sort of way.

Again, it must be stated that Iso’s depiction of the closed society of children is remarkably convincing. Hiroshi slides into a natural fit as Touya’s disciple, and Touya begins to act uncharacteristically like a big brother. Mina is frankly pretty annoying, but in a rather realistic fashion. She has a role to play here, and as unflattering as it may be it’s basically that of the majority of people and how they go through their lives (superficially). Konoha is mostly a background figure, but her journey towards acceptance of her own seemingly imminent death is quite heartbreaking in an understated sort of way.

One will obviously know a lot more after the final two episodes, but it’s interesting to ponder just what sort of future Iso is depicting here. Humanity seems split between those who want to literally throttle advancement, and those who want to embrace it. Not only that, but there’s a prominent role for religious extremism here, as a cult of Seven has emerged in response to the poem it composed before it was put to death. The shock reveal is that Nasa is a member of this cult – the John Doe referenced in the first two eps – and is in fact responsible for what’s happened at Anshin. Seven had proposed that 36.9% of humanity must be euthanized for the species to survive, and John Doe is determined to make that happen (using the corporate comet).

One will obviously know a lot more after the final two episodes, but it’s interesting to ponder just what sort of future Iso is depicting here. Humanity seems split between those who want to literally throttle advancement, and those who want to embrace it. Not only that, but there’s a prominent role for religious extremism here, as a cult of Seven has emerged in response to the poem it composed before it was put to death. The shock reveal is that Nasa is a member of this cult – the John Doe referenced in the first two eps – and is in fact responsible for what’s happened at Anshin. Seven had proposed that 36.9% of humanity must be euthanized for the species to survive, and John Doe is determined to make that happen (using the corporate comet).

It must be noted that Touya, too, spoke out in favor of that – as Mina revealed to the world in her peevish act of uploading videos of him saying so. But he was a child with no concept of the individuals that made up that 36.9% – and that’s really the most interesting element of this thread. The “Second Seven” that takes over the comet has, as Light-Dark (fused, as that was the only way Taiyou would agree to remove Dakky – “Darkness Killer’s” – cognitive limiters) notes, a view of “humanity” and “humans” as separate entities. Its priority is humanity, and sees no conflict in eliminating the “other” that make of 36.9% of the species. Neither did Touya – but expanding his experiences is expanding his horizons (which is where the coming-of-age element comes in).

It must be noted that Touya, too, spoke out in favor of that – as Mina revealed to the world in her peevish act of uploading videos of him saying so. But he was a child with no concept of the individuals that made up that 36.9% – and that’s really the most interesting element of this thread. The “Second Seven” that takes over the comet has, as Light-Dark (fused, as that was the only way Taiyou would agree to remove Dakky – “Darkness Killer’s” – cognitive limiters) notes, a view of “humanity” and “humans” as separate entities. Its priority is humanity, and sees no conflict in eliminating the “other” that make of 36.9% of the species. Neither did Touya – but expanding his experiences is expanding his horizons (which is where the coming-of-age element comes in).

This is all quite a mess. Nasa stops the UN2 nuke that was about to destroy the comet along with all hope of saving everyone on the station including her, but she’s still determined to wipe out that 36.9%. A heartless, anti-science global authority going up against a doomsday cult – it doesn’t seem like a very hopeful future at all, really. But Iso’s sensibilities don’t generally run so far in that direction (unless the last 15 years have fundamentally changed him). I expect the final two episodes to focus mainly on the views of the titular children, because it’s in children that Iso has always managed to see a reason for optimism.

This is all quite a mess. Nasa stops the UN2 nuke that was about to destroy the comet along with all hope of saving everyone on the station including her, but she’s still determined to wipe out that 36.9%. A heartless, anti-science global authority going up against a doomsday cult – it doesn’t seem like a very hopeful future at all, really. But Iso’s sensibilities don’t generally run so far in that direction (unless the last 15 years have fundamentally changed him). I expect the final two episodes to focus mainly on the views of the titular children, because it’s in children that Iso has always managed to see a reason for optimism.