This certainly represents my first second-generation interview for LiA. A few years ago, I had the pleasure of sitting down with Oscar-winning director Michaël Dudok de Wit to discuss The Red Turtle, his Oscar-nominated collaboration with Studio Ghibli. In the aftermath of that interview I began an occasional correspondence with Michaël’s son Alex. Deputy Editor at Cartoon Brew magazine and animation correspondent for BFI’s Sight & Sound magazine, Alex Dudok de Wit is one of journalism’s most authoritative voices on animation and a frequent commenter on today’s anime landscape.

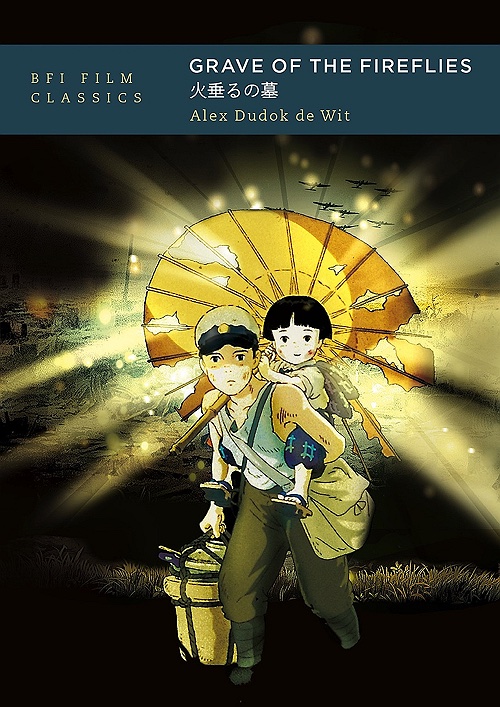

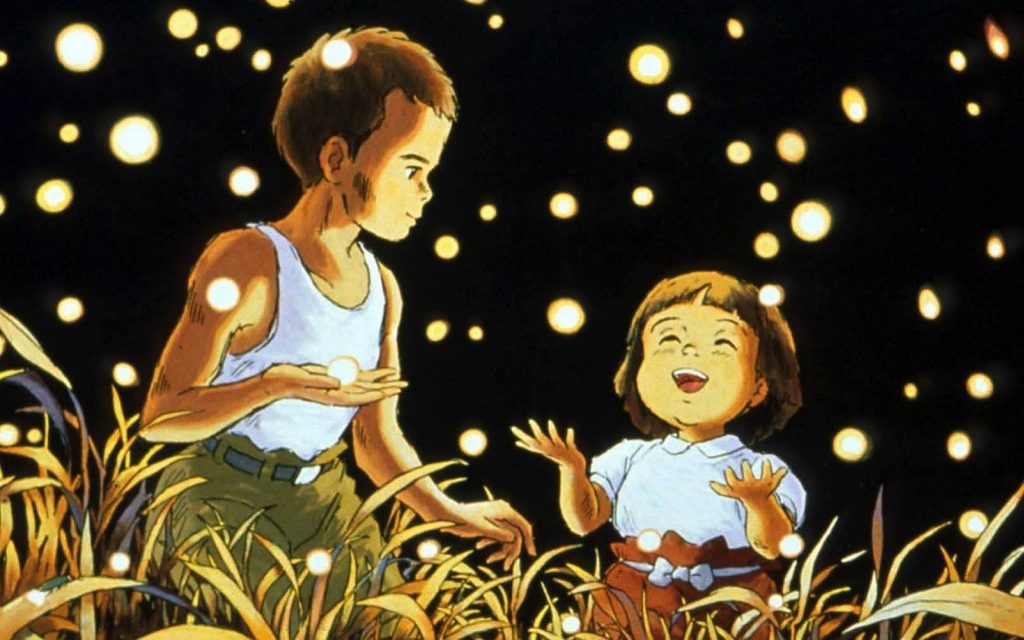

Mr. Dudok de Wit has now written BFI Film Classics: Grave of the Fireflies, the first (somewhat remarkably) full-length English-language exploration of Takahata Isao’s adaptation of Nosaka Akiyuki’s harrowing memoir of the final days of World War II. I had the privilege to discuss the book and its subject with Alex. Grave of the Fireflies has been a massively influential film (Roger Ebert called it the most powerful anti-war film ever made), and it certainly impacted me profoundly. In fact until preparing for this interview I did not watch the film for many years, simply because it’s so emotionally devastating.

Fireflies is now regarded as a classic, but its reception upon release was more complicated. So is its legacy and place in the Ghibli oeuvre. Fittingly so, as Takahata himself was a famously complicated and difficult man. I asked Alex about the film and its impact on him, the fascinating history of Studio Ghibli and Takahata’s place in it, and how this groundbreaking film is viewed today.

Lost in Anime: You talk of the “sanitized” relationship between Seita and Setsuko (and Seita’s character generally) as compared to the novella. Does this ultimately for you represent a failure of the film, or a creative choice? Was it an unavoidable compromise by Takahata given the medium and the circumstances of its production?

Alex Dudok de Wit: The novella alludes to Seita’s frustrations with Setsuko and the burden of care he’s shouldering – and also to his sexual frustrations, as a teenager with no outlet for his libido. In the film, these things are barely hinted at, if at all.

The novella is a kind of stream-of-consciousness text, so it’s fairly easy to evoke some of the darker thoughts that cross Seita’s mind. I don’t know how a film would convey these things unless it had a voiceover narrator – which Fireflies doesn’t have for 99% of its runtime – or made Seita act on these thoughts or say them aloud, which would completely change the effect Nosaka creates. So it’s partly a question of the difference between literature and cinema as mediums.

Also, Takahata is clearly aiming for a broader audience. The story was published in an adult literary magazine while the film was released alongside My Neighbour Totoro and seen by families. It was very much a deliberate choice, and not a mistake or a failure, to present Seita in a slightly different light. The result is that the film is more straightforwardly sentimental than the novella, and arguably more moving and effective as a tragedy.

L: What was the ultimate impact of Fireflies being released on the double bill with Totoro? Do you think the film would be perceived differently now if that had not been the case?

A: I don’t think it has made a huge difference. Not many people saw the films as a double bill, and nowadays few outside Ghibli fandom even know they came out together in Japan. I’d recommend watching them side by side, though. They are interested in so many of the same things – death, the beauty of nature, recent Japanese history, the grey area between childhood and maturity – and sometimes feel like mirror images of each other, one light, one dark.

L: What’s interesting to me is that while Totoro has taken on a status as a quintessential Ghibli film – perhaps the quintessential to some – Fireflies is relatively rarely discussed in the Ghibli context. Its legacy is large, but more as a stand-alone idea than as a studio work. Do you think this reflects that to an extent, Ghibli and Miyazaki are synonymous in many minds?

A: Totoro is a special case even among Miyazaki’s works, as the character is the studio’s logo. But yeah, Miyazaki and Ghibli are synonymous to many. Rayna Denison has written about the blurring of the two “brands” in the marketing of their films outside Japan – it’s an interesting subject.

In the case of Fireflies, it doesn’t help that the film’s rights situation is different from the others’, for finicky historical reasons. This means it was never distributed by Disney and is not part of the recent deals with HBO Max and Netflix. This has marginalised it a little in discussions of the Ghibli catalogue.

L: It seems ironic that Fireflies today is viewed primarily in two ways – as a tear-jerker and as an anti-war film – neither of which Takahata says he intended. Does that make the movie a partial failure, or simply imply that Takahata misinterpreted the impact of his own work?

A: Takahata was wary of films that just try to make people cry, and he’d hoped more people would take Fireflies as a prompt to think about how people act in a crisis, how individuals relate to the society around them. On his terms, then, the film partly failed, and I say so in my book.

But I also say that a film doesn’t exist purely to convey the director’s message. If people are very moved by Fireflies, or take it as a powerful statement against war, then it has succeeded in a different way. Clearly, this isn’t a complete accident: Takahata did want to show the horrors of the war’s end, and he did want to tell a tragic story. He may just have underestimated how effective his film would be in these respects!

I describe Takahata’s intentions for Fireflies in detail in the book, but that isn’t in order to say, “Here’s the correct way to understand the film.” I think that by comparing his intentions with the most common interpretations, we can learn a lot about how the film works its power.

L: Once a film is released, it no longer belongs to the writer or director, it belongs to the viewing public – do you share that view? That, more than the creators’ intent, determines on what level a movie “succeeds.”

A: I do, more or less, but that doesn’t mean we shouldn’t try to understand what the creators intended. There’s little use in saying, “Grave of the Fireflies fails because it isn’t funny enough,” to give a caricatured example.

The creators don’t decide the “right” and “wrong” ways of interpreting the film – there’s no such thing – but comparing their intentions for the film with our reactions as viewers can yield insights. That’s why we tend to be interested in what writers and directors have to say about their work.

L: The double suicide metaphor is an interesting one, given its prominence in all forms of Japanese narrative media for centuries. Is this the best way to view Fireflies structurally, in your view?

A: Takahata and Nosaka both acknowledged double suicide tales as a reference point, and the film seems to channel many of its tropes, from the use of nature metaphors to the obvious inevitability of the children’s deaths. But it also breaks with the genre in some ways. Seita and Setsuko aren’t exactly romantic lovers, so the dynamic between them is different from what you’d expect in a double suicide tale.

In combining tragedy with a focus on everyday details, the film also reminds me of neorealist cinema: De Sica, Rossellini, etc. Double suicide tales were traditionally told in kabuki and puppet theater, which like animation is overtly artificial, while neorealism aimed for a naturalistic, documentary-like aesthetic, which reminds me of what Takahata often tried to do within animation. So I like thinking of Fireflies as a kind of cross between the two. Of course, there are other ways to look at the film’s structure, too.

L: More than any other live-action war film Fireflies reminds me of Rossellini’s Rome, Open City, which I first saw in a film class in college. Perhaps it’s the degree to which that movie impacted me but I feel as if I can see its influence in both the writing and direction of Fireflies.

A: I saw Rome, Open City a long time ago. I don’t remember the details! Fireflies also reminds me of Rossellini’s Germany, Year Zero and De Sica’s Shoeshine, as well as Mira Nair’s Salaam Bombay!. Great films, all of them. Takahata’s feature is an example of “neorealist animation,” to my eyes. There’s a term you don’t hear much!

L: Can you briefly elaborate further on Suzuki’s role specifically in getting Fireflies across the finish line, when Takahata himself seemed ready to give up on it? He seems to be very much the “indispensable man” of Ghibli, without whom it would all have fallen apart many times over.

A: Toshio Suzuki is a fascinating guy whose role at Ghibli hasn’t been fully laid out in English-language scholarship yet, although in Japan he’s much better known. He played a key role in getting Fireflies greenlit by orchestrating the double bill with Totoro, and remained involved in the project after that.

But it’s important to stress that he wasn’t officially a producer on the film – in fact, he isn’t credited at all (though he is on Totoro, as part of the production committee). At the time, he was still an editor at Animage magazine, and had yet to formally join the studio. A number of producers helped steer Fireflies past the finish line, not least Toru Hara, the former Topcraft chief who was managing Ghibli by this point. He deserves more credit than he gets.

L: Could you share your thoughts on Ghibli as “anime”? While it literally is, it tends to be thought of differently by non-Japanese, both anime fans (who seem to almost resent Ghibli for its mainstream success) and non-anime fans. On that note, do you feel either Takahata or Miyazaki is more expressly an “anime filmmaker” than the other?

A: Yeah, I think this notion has to do with Ghibli’s popularity, as you say, and also in part with the marketing of its films. In the West, the films have generally received a kind of arthouse branding, with Miyazaki and Takahata pushed as “auteurs,” while also getting distribution from Disney in the past. And there’s the Oscar.All of which encourages people to see Ghibli, somewhat paradoxically, as both highbrow and popular, in contrast to the “lowbrow and niche” image a lot of anime still (sadly) suffers from here.

In Japan, too, Ghibli has tried to distinguish its work from other anime. In The Anime Machine, Thomas Lamarre shows how the studio has characterised its features as “manga eiga” – manga films – and not “anime,” emphasising its use of relatively full animation and focus on theatrical releases, not series. Takahata stressed his debt to animation from Europe, Canada; he was not always very complimentary of contemporary anime (this interview is a good example).

Behind all this branding is an idea of what anime should be: what stories it should tell, what techniques it should use. I’m not interested in limiting the term in that way. As far as I’m concerned, Takahata and Miyazaki worked within the anime industry and can’t be separated from it. I say that while knowing full well that they did some quite radical things within the industry, and eventually worked with budgets that other anime filmmakers could only dream of.

L: In point of fact not just Takahata but Miyazaki too have expressed discomfort with anime and being associated with it. In a sense there’s a kind of tacit collaboration between Ghibli’s icons (though notably not Suzuki) and anime “purists” to distinguish the one from the other. I feel as if this is a largely false distinction, and more pervasive outside Japan than within it. Ghibli has taken to producing series anime on occasion (like Ronja), making the distinction even more tenuous.

On another note: Do you feel America having never lost a war until Vietnam impacts their view of a WWII film?

A: It’s a good question. I don’t know. But I think America’s experience of WWII is important here. Not only was the country emphatically on the winning side, it has found it relatively easy to construe its rationale for fighting – a stand against fascism – as morally good. In my country, the UK, it’s the same: we stood strong against the evil Nazis.

That doesn’t mean all Americans think everything their country did in WWII was good, of course. After watching Fireflies, the critic Roger Ebert was moved to reflect on the horrors of his country’s firebombing campaign. Yet American society at least has a dominant narrative of the war that it can rally around. Japan does not: it lost and has had to reckon with the legacy of its empire, which did awful things, and the ideology that underlay it, which was discredited after the war.

In that sense, America’s memory of Vietnam, or Iraq, has things in common with Japan’s memory of WWII. There’s a general sense of failure, of moral doubt; the meaning of the conflict is fiercely contested. Maybe these experiences have led some Americans, like Ebert, to re-examine some of what their side did in WWII, too. After all, the firebombing of Japan looks a lot like the napalm strikes on Vietnam.

L: You touch on The Wind Rises in your final chapter, and it strikes me as very much a companion piece to Fireflies in the Ghibli oeuvre. I agree with you that Miyazaki seems to have abdicated on judging Horikoshi for the impact of his work on the war. Do you think Takahata would have handled the denouement differently? I’m linking my review of the film, as I think you might find it relevant – I believe our interpretations are more or less in agreement (bear in mind at the time I wrote it, Miyazaki had – not for the first time – announced he was finished as a theatrical director).

A: Suzuki wanted Miyazaki to make The Wind Rises as a way to confront the contradiction inside him, and supposedly inside Horikoshi: they are pacifists who love military machines. But the film doesn’t really explore what effect this contradiction has on Horikoshi’s psychology, even though it takes us inside his mind in the form of dream sequences. So when the film occasionally reminds us of the awfulness of war – usually through the words of another character – it feels almost irrelevant to the story.

That’s the problem with the ending, which shows us all the wrecked Zeros. Takahata directly told Miyazaki that he would have wanted the film to show more of the deaths caused by the Japanese army, to give context to the ending. He added that, this way, young viewers would have learned more about their country’s part in the war. In his hands, I think The Wind Rises would have been more psychological and more explicit in the way it examined morality. And he wouldn’t have dedicated the film to Horikoshi, as Miyazaki did.

L: To follow up, it almost strikes me that one could view Rises as more of a stereotypical Takahata project thematically, and Princess Kaguya more a Miyazaki one. In a way, that Miyazaki directed the Takahata film, and vice-versa, with fascinating results. Do you get that sense at all?

A: I guess you mean that Kaguya is more overtly fantastical? I kind of know what you mean, but Kaguya also seems so Takahata to me. I see it as a film about how to navigate society in all its complexities, and how we derive meaning from strong connections with people (as well as the natural world). Takahata really builds that up from the original folk tale. I’d have loved to see what Miyazaki would do with the story, though.

As for The Wind Rises, I’m not sure Takahata would have made a film like this at all. After Fireflies, he wanted to direct a feature set in Asia as the Japanese Empire was encroaching on the continent (I wrote about it here). The project didn’t work out, but it suggests that, if he had made a film about that period of build-up to the war, he would have preferred to tell the story from the other side’s perspective.

L: From my perspective it’s more that if you imagine a Ghibli director updating an ancient folk tale, it’s Miyazaki who comes to mind before Takahata. I wouldn’t change a moment of Kaguya because it’s a masterpiece, but like you I would have loved to have seen what Miyazaki would do with it too.

I agree that Takahata wouldn’t have made The Wind Rises (I don’t see him as someone who would have admired Horikoshi the way Miyazaki does). But in our mind’s eye it still strikes me as thematically more a Takahata film than Miyazaki – the flipside of that “which Ghibli director would first spring to mind” question about Kaguya, I suppose it’s an object lesson that both films – and both directors – are quite different than superficial impressions would suggest.

You’re probably aware that Barefoot Gen has been banned by numerous libraries in Japan since Abe’s (re)election. Did Takahata ever comment on this to your knowledge, and how do you think it fits with his concerns about how modern Japanese view the war?

A: As far as I know, Takahata never spoke about this publicly. I’m sure he saw it as part of a dangerous revisionist agenda, which is what it seemed to be. I think the ban was later reversed, wasn’t it?

L: The most famous ban, in Matsue, was eventually reversed – but on “procedural grounds.” But there have been other cases (in an Osaka suburb for one) that as far as I know were not reversed.

While Abe is no longer in power his ideological faction remains dominant, and as you note there are things happening in Japanese politics today which would have been unthinkable when Fireflies was made. The pandemic has deferred the push to amend Article 9, but not ended it. Where do you see this ending up?

A: Like many, I’m concerned that opportunistic politicians will seize on the geopolitical upheaval – the rising belligerence of China, the growing tensions with both Koreas, etc – to push their case for revision. I’m also aware that the Japanese public still seems unlikely to approve an outright amendment. Even Abe didn’t have the political capital to call a referendum.

On a more general level, I think Takahata was right to worry that the passing of the WWII generation is weakening our sense of the horror of war — not just in Japan, but everywhere.

L: I have one more question if I may. For decades we’ve heard talk of the “next Miyazaki.” Hosoda Mamoru, Shinkai Makoto, Hayao’s own son Goro – all had the mantle thrust upon them at one time or another, despite it being rather ill-fitting in each case. Yet we never hear talk of a “next Takahata.” Is this simply a matter of Miyazaki being the more commercially successful director, or is there something more innately singular about Takahata that discourages anyone from thinking in those terms?

Miyazaki has a unique place in the industry: he’s a global icon, a kind of Disney of anime, and it seems many people need a talismanic figure like that. The idea of a brilliant, charismatic filmmaker becoming a box-office phenomenon while keeping his creative integrity, and boosting the international profile of anime in the process, is a seductive one. Talk of the “next Miyazaki” seems to be more about this – about the hope that it can happen again – than anything specific to his art.

Takahata’s legacy is massive, but less obvious from outside the industry. I think that’s why there isn’t so much talk of the “next Takahata”: what would that mean, exactly?

Kim

June 27, 2021 at 8:38 pmFantastic interview. Grave of Fireflies has always been one of my favorite films and I always wished Takahata got the same level of recognition Miyazaki received. But Takahata was definitely more of an art house director. Critically well regarded just couldn’t produce the same box office.

And I loved the comparison of Grave to Italian Neorealism films. I love those movies. It’s especially great to see Shoeshine mention. I really want Criterion to license that one. And thinking about it while I do think Takahata’s works fit well under the Gkids umbrella they probably would be a perfect fit for the Criterion collection as well.

Guardian Enzo

June 27, 2021 at 9:11 pmI would love to see Criterion releases for Takahata’s films. But they’re all Ghibli and all under the same distribution model (though this one is an exception, as Alex notes in the interview).

Raikou

June 28, 2021 at 8:35 amI guess I’m late to know this, but I just heard that Grave of the Fireflies has a novel.

Thanks for this interview, Enzo. Come to think of it, this is the first time I saw your takes about Ghibli Movies (or maybe you posted before but I never saw it). What are your favorites?

Guardian Enzo

June 28, 2021 at 1:09 pmWell, it’s based on a memoir – fictionalized (obviously) but very much based on true events and emotions. The author was quite involved in the making of the movie.

I have written on many Ghibli films – and Ronja too, a bit. The posts are there to search or just look in the Movie/OVA tag. My favorite is Mononoke Hime to be sure, but after that it’s a very close call. Fireflies and Kaguyahime would be there, and my pick for the most underrated Ghibli film would probably be Castle in the Sky.

Raikou

June 28, 2021 at 6:41 pmRight, I just found it. I’ll be reading those.

I love Mononoke Hime too, it’s really one of the best Ghibli. Maybe I’m going to watch Kaguyahime soon.

Castle in the Sky is underrated? I thought many liked that.

Derrick

June 28, 2021 at 10:03 amInteresting note about Takahata intentions.

That was pretty japanese , “how to cope with crisis and to relate with others”

leongsh

June 28, 2021 at 4:34 pmIt’s been a while since I last watched “Grave of The Fireflies”. I am not surprised by how Takahata wanted the movie to be viewed as. Incidentally, that’s generally how I viewed it as. Not so much as an anti-war film but a film that shows the many mistakes made by all around, too much pride, the selfishness that arises in order to survive during times of crisis, etc. Preventable deaths but the spiral downwards saddened me a lot but also made me angry.

Skidda

June 29, 2021 at 4:01 amThanks for this interview.

I watched ‘Grave of the Fireflies’ at school and like many people I haven’t got the courage to watch it again yet (though it’s been in my mind more and more these past years).

And now I’m bummed out because I didn’t know about 1939 Border and I would’ve loved to see Takahata make it.

Guardian Enzo

June 29, 2021 at 6:38 amWow, where was this? I’m impressed they showed that in school.

Skidda

June 29, 2021 at 7:11 pmBelgium. Is that surprising ? It’s (well I guess it’s still the case) usual to show some anti-war stuff at school around here, at least in France/Belgium/Germany. In high school most students had to watch ‘Nuit et Brouillard’, a short documentary about concentration camp (it’s pretty traumatizing) for example.

But in the case of Grave of Fireflies, it was just a lazy teacher (a lay teacher, like an ethic/civic teacher I guess) showing us some random movies. We even got the first Matrix movie at one point.

Kinai

July 16, 2021 at 10:07 pmOh! I know that type of teacher. But in our case, it was Monty Python’s Life of Brian. 😀

Kinai

July 16, 2021 at 7:43 pmI think that THIS is the only film from Studio Ghibli that I am not going to see.

I have already too many issues with depression already in my life.

Guardian Enzo

July 16, 2021 at 7:59 pmThat’s a shame. I wish I could tell you it’s not a depressing film, but it’s a downer without a question. It’s bloody brilliant too, though, for what that’s worth.

Kinai

July 16, 2021 at 10:04 pmI know. I know that it’s brilliant, perhaps the best film of animation on the whole history. But I am too sensitive to that type of films. 🙁

DonkeyWan

July 20, 2021 at 11:19 pmA film I frequently reference as both the best and hardest watch. A film so moving and so devestating that to watch it a second time would almost feel like self-harm.

Guardian Enzo

July 21, 2021 at 9:07 pmI had already seen it more than once but it been at least 10 years since the last time when I watched it to prepare for the interview. It is a tough thing to experience.