I know that these posts are the least read on the website by a comfortable margin – the view counts tell a clear story. And I absolutely don’t blame anybody – this is a nearly decade-old series that was esoteric as hell even when it was new. But it’s worth mentioning over and over – Hyouge Mono is a masterpiece. It truly is great. And it truly is pretty much unique, in anime terms. Both those things are rare as hen’s teeth, but to get them in the same show is a unicorn among unicorns.

I know that these posts are the least read on the website by a comfortable margin – the view counts tell a clear story. And I absolutely don’t blame anybody – this is a nearly decade-old series that was esoteric as hell even when it was new. But it’s worth mentioning over and over – Hyouge Mono is a masterpiece. It truly is great. And it truly is pretty much unique, in anime terms. Both those things are rare as hen’s teeth, but to get them in the same show is a unicorn among unicorns.

We’re getting pretty close to the end now, and the shape of the new world that’s emerging for these fascinating men from this time of tumultuous change is becoming clearer. Sasuke notes himself that the time may finally be arriving where he must decide whether he follows the way of the warrior or the aesthete. And indeed, that’s very much a theme of the episode. Sasuke has an especially interesting moment where he applies his obsession with aesthetics to the Odawara campaign, noting that that dirt is unsuitable for pottery because it’s too powdery and loose. Unfortunately Ishida has constructed a levee from that dirt, and before Sasuke can take action it collapses, killing many of his men.

We’re getting pretty close to the end now, and the shape of the new world that’s emerging for these fascinating men from this time of tumultuous change is becoming clearer. Sasuke notes himself that the time may finally be arriving where he must decide whether he follows the way of the warrior or the aesthete. And indeed, that’s very much a theme of the episode. Sasuke has an especially interesting moment where he applies his obsession with aesthetics to the Odawara campaign, noting that that dirt is unsuitable for pottery because it’s too powdery and loose. Unfortunately Ishida has constructed a levee from that dirt, and before Sasuke can take action it collapses, killing many of his men.

I’ve noted this before, but while Sasuke may play the fool a fair amount of the time, he’s no fool. He calls Ishida on the carpet for his failures in the siege, and Ishida (stinging because he knows Oribe is right) petulantly lashes out by calling him a “tea-obsessed bastard”. Sasuke doesn’t deny the charge, but notes that his obsession means that whenever he undertakes a project he investigates every minute detail. Ishida is arrogant to be sure, but he’s also unwaveringly loyal to Hideyoshi – an increasingly rare quality that the Monkey recognizes as precious – and that gives him considerable leeway another man might not be given.

I’ve noted this before, but while Sasuke may play the fool a fair amount of the time, he’s no fool. He calls Ishida on the carpet for his failures in the siege, and Ishida (stinging because he knows Oribe is right) petulantly lashes out by calling him a “tea-obsessed bastard”. Sasuke doesn’t deny the charge, but notes that his obsession means that whenever he undertakes a project he investigates every minute detail. Ishida is arrogant to be sure, but he’s also unwaveringly loyal to Hideyoshi – an increasingly rare quality that the Monkey recognizes as precious – and that gives him considerable leeway another man might not be given.

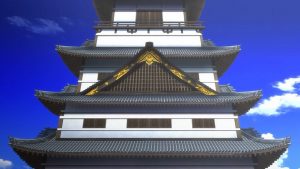

As the Houjou finally fall, Hideyoshi’s one-night castle trick working exactly as it was intended, the minds of the warriors begin to turn towards the future. Rikyu has received the stirrups – and poem – from Sasuke, and gratefully replies with a gift and poem of his own. Sasuke has no idea of how far his master has fallen, but it seems Rikyu is quite aware himself of his deteriorating state of mind. Meanwhile the focus turns to Nobukatsu, the son of Oda Nobunaga. Hideyoshi faces the momentous task of assigning his generals to far-flung regions of the country as he prepares to invade China, and Nobukatsu is the one who seems most likely to refuse.

As the Houjou finally fall, Hideyoshi’s one-night castle trick working exactly as it was intended, the minds of the warriors begin to turn towards the future. Rikyu has received the stirrups – and poem – from Sasuke, and gratefully replies with a gift and poem of his own. Sasuke has no idea of how far his master has fallen, but it seems Rikyu is quite aware himself of his deteriorating state of mind. Meanwhile the focus turns to Nobukatsu, the son of Oda Nobunaga. Hideyoshi faces the momentous task of assigning his generals to far-flung regions of the country as he prepares to invade China, and Nobukatsu is the one who seems most likely to refuse.

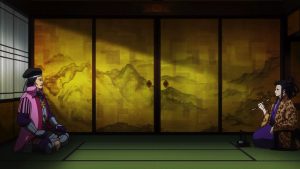

In this mythology of course, Hideyoshi has special reason to feel disquiet when dealing with the Oda clan. He prevails on Chacha – the mother of the son he plans to have succeed him and an Oda cousin – to try and persuade Nobukatsu, through the boy’s uncle Nagamasu (Nobunaga’s brother). But Nagamasu doesn’t have the heart for the task himself, being primarily concerned with staying in his beloved Kyoto. Nagamasu was a fascinating man, a Christian by conversion and a renowned master of tea, and in Hyouge Mono’s version of events he finally renounces fealty to both Hideyoshi and Chacha and decides to throw away his rank and privilege, becoming a monk.

In this mythology of course, Hideyoshi has special reason to feel disquiet when dealing with the Oda clan. He prevails on Chacha – the mother of the son he plans to have succeed him and an Oda cousin – to try and persuade Nobukatsu, through the boy’s uncle Nagamasu (Nobunaga’s brother). But Nagamasu doesn’t have the heart for the task himself, being primarily concerned with staying in his beloved Kyoto. Nagamasu was a fascinating man, a Christian by conversion and a renowned master of tea, and in Hyouge Mono’s version of events he finally renounces fealty to both Hideyoshi and Chacha and decides to throw away his rank and privilege, becoming a monk.

There are multiple layers to the pun involving Nagamasu’s new name that I’m afraid are beyond my Japanese ken, but the gist of it seems to be that he chooses a name (Murakusai) meaning “deprivation”, and Hideyoshi assigns him one (Yurakusai) meaning “luxury”. The chief advisor, in fact, refuses to let Nagamasu go into seclusion – ordering him instead to remain at his side and become his “bantering partner for life”. This is a fanciful exchange, surely, but nevertheless rather moving. Hideyoshi’s sense of isolation is quite remarkable and probably not far from the truth.

There are multiple layers to the pun involving Nagamasu’s new name that I’m afraid are beyond my Japanese ken, but the gist of it seems to be that he chooses a name (Murakusai) meaning “deprivation”, and Hideyoshi assigns him one (Yurakusai) meaning “luxury”. The chief advisor, in fact, refuses to let Nagamasu go into seclusion – ordering him instead to remain at his side and become his “bantering partner for life”. This is a fanciful exchange, surely, but nevertheless rather moving. Hideyoshi’s sense of isolation is quite remarkable and probably not far from the truth.

Finally, we have Tokugawa Ieyasu, the man who would emerge from all this as the most dominant figure in the past half-millennium of Japanese history. He’s the odd man out among Hideyoshi’s elites, no aesthete and possessed of no aspiration to become one. The world he would shape would look very different from the cloistered shell of Kyoto. And Hideyoshi has given him license to do just that in Edo, a task which fills the prosaic but relentless Ieyasu with joy. For the Monkey this may have seemed the safest course, Edo a far-away wasteland of little consequence. But he failed to reckon with Tokugawa’s tremendous sense of vision, albeit one very different from his own, and it’s the servant who would have the last laugh.

Finally, we have Tokugawa Ieyasu, the man who would emerge from all this as the most dominant figure in the past half-millennium of Japanese history. He’s the odd man out among Hideyoshi’s elites, no aesthete and possessed of no aspiration to become one. The world he would shape would look very different from the cloistered shell of Kyoto. And Hideyoshi has given him license to do just that in Edo, a task which fills the prosaic but relentless Ieyasu with joy. For the Monkey this may have seemed the safest course, Edo a far-away wasteland of little consequence. But he failed to reckon with Tokugawa’s tremendous sense of vision, albeit one very different from his own, and it’s the servant who would have the last laugh.

Derrick

December 14, 2020 at 12:12 amWith domestic matters still in tumult, one will wonder why would a small nation island would take the challenge of fighting the Ming. Can’t imagine the logistical nightmare.

Guardian Enzo

December 14, 2020 at 7:40 amThat was not an unpopular opinion at the time (and since).

Skidda

December 14, 2020 at 6:41 pmWell after all the conflicts from that period, the samurais had become pretty good at (land) war and going regularly on campaign was pretty much their way of life at this point. But yes we’re talking about napoleonic scale in the 16th century so it was very much a logistical nightmare.

As for the why, focusing on an external enemy and land was a good solution for Hideyoshi (and Nobunaga) to unite the daimyos, sending some of them away while consolidating his power in Japan with the more loyal ones (if I remember correctly).

Also, as the anime showed, a big part of building up loyalty for Nobunaga/Hideyoshi (and any feudal lords for that matter) was to share the spoils of war between his vassals. Since they were running out of juicy targets in Japan, invading foreign lands was a way to sustain that system.

And as for why the Ming dynasty, its tributary system meant that unless Japan accepted to become ‘vassalized’ (on paper at least), they couldn’t trade with them freely. One theory is that Hideyoshi never expected to conquer China but wanted to display enough power/threat to appear their equal and stop being the considered the leader of a ‘remote uncivilized island’. Personally, I think it was more about powerful people wanting more power.

Anyway, very good episode (always liked Nagamasu in this show). It was noted during last episode how lonely Hideyoshi had become and this episode very much hammered that point. Any series that can make me feel sympathy for terrible people is a good one (Vinland Saga was also good at that).

Guardian Enzo

December 15, 2020 at 6:36 pmI’m not so sure I’d go along with Hideyoshi as a terrible person, at least as measured against his peers as wannabe-uniters of Japan and Shoguns. Though of course in this version he did cut Nobunaga in half…