At the risk of initiating a Newman “what took you so long?” moment, I’m going to directly compare Chihayafuru and Kono Oto Tomare! now. And it only took a week of them airing side-by-side, too. That was enough to frame this for me in a way that seems deceptively simple but never before struck me quite so unmistakably. The difference between these two series is movement. Chihayafuru is the more lavishly-produced series, and Suetsugu-sensei the more elegant and technically accomplished writer. But Kono Oto Tomare has a flow which Chihayafuru has totally lost. People change, things move forward. The great sense of frustration I feel with Chihayafuru’s “Groundhog Day” syndrome never happens with KoT, because while the cast are always facing challenges, those challenges are always changing because the characters actually grow.

At the risk of initiating a Newman “what took you so long?” moment, I’m going to directly compare Chihayafuru and Kono Oto Tomare! now. And it only took a week of them airing side-by-side, too. That was enough to frame this for me in a way that seems deceptively simple but never before struck me quite so unmistakably. The difference between these two series is movement. Chihayafuru is the more lavishly-produced series, and Suetsugu-sensei the more elegant and technically accomplished writer. But Kono Oto Tomare has a flow which Chihayafuru has totally lost. People change, things move forward. The great sense of frustration I feel with Chihayafuru’s “Groundhog Day” syndrome never happens with KoT, because while the cast are always facing challenges, those challenges are always changing because the characters actually grow.

Growth is, needless to say, both desirable and important in a series of this nature. My respect for Komo Oto Tomare has grown over time because what it lacks in flash it makes up for in substance. While it’s certainly not for me to say, my impression is that a good percentage of the anime’s audience (small though it seems to be) don’t really get this show. It’s not about the performances – though its greatest moment was a performance. It’s not about romance, though romantic feelings color so much of the narrative. If I were to point to an episode that exemplifies KoT it wouldn’t be Episode 5, or last week’s – it would be this one. And maybe that’s part of the anime’s problem in drawing a larger audience.

Growth is, needless to say, both desirable and important in a series of this nature. My respect for Komo Oto Tomare has grown over time because what it lacks in flash it makes up for in substance. While it’s certainly not for me to say, my impression is that a good percentage of the anime’s audience (small though it seems to be) don’t really get this show. It’s not about the performances – though its greatest moment was a performance. It’s not about romance, though romantic feelings color so much of the narrative. If I were to point to an episode that exemplifies KoT it wouldn’t be Episode 5, or last week’s – it would be this one. And maybe that’s part of the anime’s problem in drawing a larger audience.

It’s always seemed to me that if there were one overarching theme to Koto Oto Tomare, it’s interdependence. We’re all alone in the larger sense – we’re born alone, and we die alone. But if we’re alone, we can’t truly live. It’s by putting the needs of others before ourselves that we grow and mature as human beings, and that process is the narrative impetus of everything that happens in this series. If one looks at Takezou, Hoozuki and Chika as the three main pillars of the story this certainly applies to them – but it’s not limited to them. Each of them was stuck in a kind of isolated personal Hell before they found each other, and by being vulnerable they’re in the (often painfully slow) process of escaping it.

It’s always seemed to me that if there were one overarching theme to Koto Oto Tomare, it’s interdependence. We’re all alone in the larger sense – we’re born alone, and we die alone. But if we’re alone, we can’t truly live. It’s by putting the needs of others before ourselves that we grow and mature as human beings, and that process is the narrative impetus of everything that happens in this series. If one looks at Takezou, Hoozuki and Chika as the three main pillars of the story this certainly applies to them – but it’s not limited to them. Each of them was stuck in a kind of isolated personal Hell before they found each other, and by being vulnerable they’re in the (often painfully slow) process of escaping it.

When one looks at the performance side of the tale, the same themes can be applied. The players here – including the most accomplished, Hoozuki, grow both by integrating their performance with the ensemble and by learning about how a performance impacts an audience. Takinami-sensei (who’s as much an exemplar of all this as any of the protags) choosing “Yaegoromo” as the club’s piece for the national qualifiers keeps the train powering ahead. Could anyone have been more alone than she was when she played it – a lost child trying to use music to reach the one person she felt connected to, her mother – and failing utterly?

When one looks at the performance side of the tale, the same themes can be applied. The players here – including the most accomplished, Hoozuki, grow both by integrating their performance with the ensemble and by learning about how a performance impacts an audience. Takinami-sensei (who’s as much an exemplar of all this as any of the protags) choosing “Yaegoromo” as the club’s piece for the national qualifiers keeps the train powering ahead. Could anyone have been more alone than she was when she played it – a lost child trying to use music to reach the one person she felt connected to, her mother – and failing utterly?

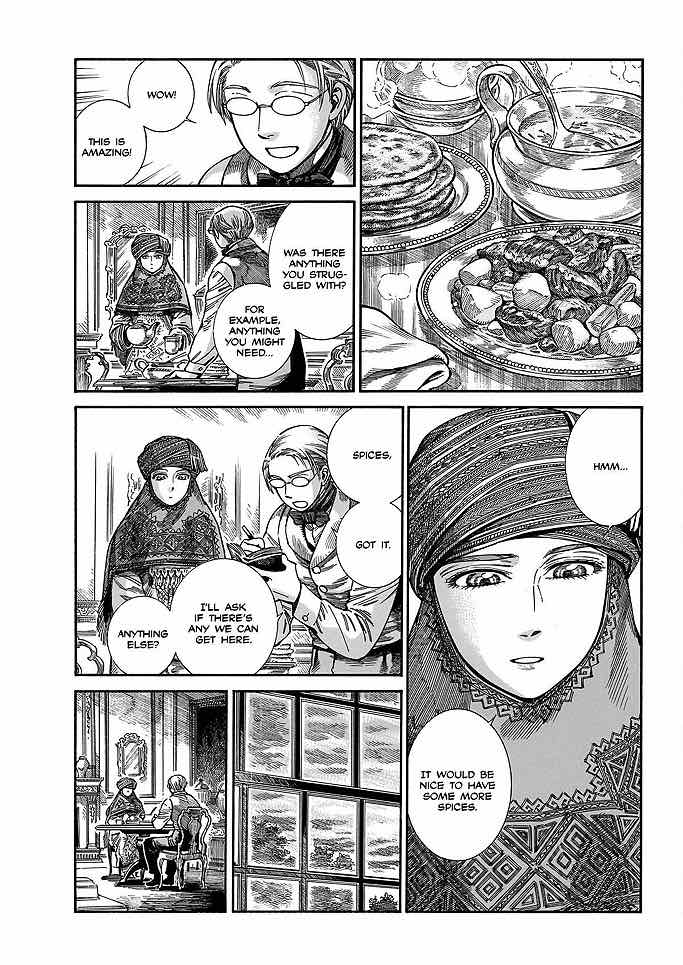

Suzuka-chan (especially with his own backstory) taking this solo piece and rewriting it (in one sleepless night) as an ensemble, well… The symbolism could hardly be more perfect. Suzuka plays the club the Hakuto performance and notes that they won because their performance was “the right answer” – a piece written specifically for them and especially, for their star performer. Tokise can never win by playing the right way – but their strength is in conveying the emotions of their members (most directly, their feelings for each other – romantic and fraternal). Satowa playing “Yaegoromo” alone failed utterly, succeeding only in “screaming” when she meant to convey her love for her mother. Suzuka will rewrite for everyone so that it represents no one individual’s feelings, but those of the ensemble.

Suzuka-chan (especially with his own backstory) taking this solo piece and rewriting it (in one sleepless night) as an ensemble, well… The symbolism could hardly be more perfect. Suzuka plays the club the Hakuto performance and notes that they won because their performance was “the right answer” – a piece written specifically for them and especially, for their star performer. Tokise can never win by playing the right way – but their strength is in conveying the emotions of their members (most directly, their feelings for each other – romantic and fraternal). Satowa playing “Yaegoromo” alone failed utterly, succeeding only in “screaming” when she meant to convey her love for her mother. Suzuka will rewrite for everyone so that it represents no one individual’s feelings, but those of the ensemble.

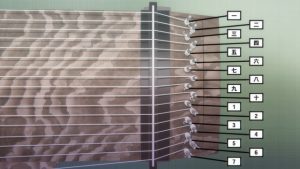

Make no mistake, it took incredible courage and humility for Satowa to do what she did in returning home to literally beg her mother to borrow a 17-string koto (which the club desperately needs to practice Takinami’s score). It was the embodiment of putting their needs above her own feelings – and of how much she’s grown as a person since the story began. It’s fucking beautiful, really – and I don’t believe I’m exaggerating in the slightest when I say that. This is honest, pure and straightforward storytelling – too much so for its own commercial good probably, but no less laudable for that.

Make no mistake, it took incredible courage and humility for Satowa to do what she did in returning home to literally beg her mother to borrow a 17-string koto (which the club desperately needs to practice Takinami’s score). It was the embodiment of putting their needs above her own feelings – and of how much she’s grown as a person since the story began. It’s fucking beautiful, really – and I don’t believe I’m exaggerating in the slightest when I say that. This is honest, pure and straightforward storytelling – too much so for its own commercial good probably, but no less laudable for that.

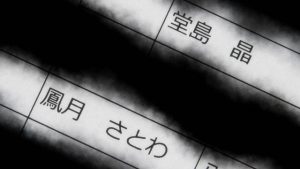

Of course all of our best intentions in life are never enough on their own. There will always be those who challenge us, who hurt us and cause us to question ourselves, and give is the option of growing enough to overcome them or to give up. In that vein we meet Doujima Akira (Touyama Nao) and her grandmother during Hoozuki’s visit home – the new live-in disciple at the Satowa School, and potentially the new heir to the style. It’s not immediately clear what Hoozuki represents to Akira, or (unlike her grandmother) why Akira feels the way she does about her. But one of the benefits of a series in which all the characters have their own story is that it’s only a matter of waiting to find out, and knowing the answers will be an important part of the narrative’s progress. It’s a rare luxury which Kono Oto Tomare provides, and it really should be appreciated more than it is.

Of course all of our best intentions in life are never enough on their own. There will always be those who challenge us, who hurt us and cause us to question ourselves, and give is the option of growing enough to overcome them or to give up. In that vein we meet Doujima Akira (Touyama Nao) and her grandmother during Hoozuki’s visit home – the new live-in disciple at the Satowa School, and potentially the new heir to the style. It’s not immediately clear what Hoozuki represents to Akira, or (unlike her grandmother) why Akira feels the way she does about her. But one of the benefits of a series in which all the characters have their own story is that it’s only a matter of waiting to find out, and knowing the answers will be an important part of the narrative’s progress. It’s a rare luxury which Kono Oto Tomare provides, and it really should be appreciated more than it is.

Earthlingzing

October 27, 2019 at 6:51 pmHmm. That’s another set of female characters who are horrible people. I really liked Hoozuki’s reaction to Akira’s taunts, it shows how she’s grown as a person.

Guardian Enzo

October 27, 2019 at 7:12 pmWould love to engage you on that comment, but as a manga reader I think I’d better not.

For the record,, though:

Hoozuki – not horrible

Hiro – not horrible

Grandma – not horrible

Chika no Onee-san – not horrible

Earthlingzing

October 27, 2019 at 9:55 pmAh, my bad, I meant start out as horrible people. Hiro and Hoozuki kind of fit into that bill for me too.

Guardian Enzo

October 27, 2019 at 10:07 pmHiro I’ll give you. Hoozuki, well – I guess it’s open to interpretation, but I didn’t see her that way.

leongsh

October 27, 2019 at 9:16 pmYou’ve sussed out the appeal of Kono Oto Tomare! Narrative flow with actual progressive development of the characters. It doesn’t run into cul-de-sacs nor spins it wheels. It doesn’t waste time and opportunity to move forward. The side characters – the trio (Sane, Kota, Michi) – are not neglected. Each have their turn within the story to have some highlight and their growth.

Guardian Enzo

October 27, 2019 at 9:35 pmIt’s not like I didn’t already know and haven’t alluded to this before, but having it run side by side with Chihayafuru really hammers home the point in an immediate fashion.

Rita

November 2, 2019 at 4:03 amThis run of the story was, for me, the strongest. And it’s definitely the one where you can clearly feel progress being made, the characters grow and struggle and come together and it’s to this day one of my favorite arcs in any sort of coming of age story (or heck, just character driven drama in general).