It strikes me that 70 is kind of a milestone for Gegege no Kitarou, at least symbolically. There are obviously quite a few long-running anime on Japanese TV (heck, Sazae-san has been on for 50 years straight!). But there haven’t been a whole lot of shows I’ve covered on this site that have gotten to 70 episodes. This one has pretty much been under the radar for most of that time, rarely among the most discussed or most viewed, but it’s quietly produced some of the best and best-looking anime of the last 17 months.

It strikes me that 70 is kind of a milestone for Gegege no Kitarou, at least symbolically. There are obviously quite a few long-running anime on Japanese TV (heck, Sazae-san has been on for 50 years straight!). But there haven’t been a whole lot of shows I’ve covered on this site that have gotten to 70 episodes. This one has pretty much been under the radar for most of that time, rarely among the most discussed or most viewed, but it’s quietly produced some of the best and best-looking anime of the last 17 months.

As for this episode itself, well- it was a bit of a strange one. Squarely in the series’ dark mode (as more of them than not have been lately), solidly Shinto in mythology. But sometimes GGGnK veers off into places where its thinking seems quite alien to me. We saw it during the “Western Youkai” arc where out of the blue, it got very xenophobic for a while. This seems to be more of an isolated one-off, but the conclusions it came to at the end of the episode felt really off to me. And more to the point, out of character for the series.

As for this episode itself, well- it was a bit of a strange one. Squarely in the series’ dark mode (as more of them than not have been lately), solidly Shinto in mythology. But sometimes GGGnK veers off into places where its thinking seems quite alien to me. We saw it during the “Western Youkai” arc where out of the blue, it got very xenophobic for a while. This seems to be more of an isolated one-off, but the conclusions it came to at the end of the episode felt really off to me. And more to the point, out of character for the series.

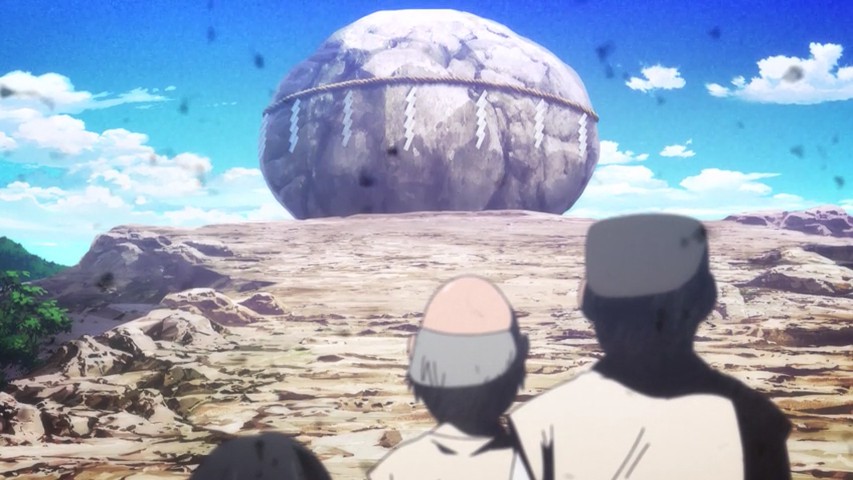

The story is all about curses (and no Hanajima Megumi in sight). A small village rests in the shadow of a mountain atop which likes the spirit stone representing the Kami Taitanbou. A certainly family has been tasked with being the stone’s guardians since time immemorial, father to son – and young Kento is the latest to have the burden thrust upon him. The rules are pretty straightforward – the guardian must offer homage to the Kami every four days without fail, and no one from outside the village must be allowed to set eyes on it. Otherwise Taitanbou’s curse will fall on the village and everyone associated.

The story is all about curses (and no Hanajima Megumi in sight). A small village rests in the shadow of a mountain atop which likes the spirit stone representing the Kami Taitanbou. A certainly family has been tasked with being the stone’s guardians since time immemorial, father to son – and young Kento is the latest to have the burden thrust upon him. The rules are pretty straightforward – the guardian must offer homage to the Kami every four days without fail, and no one from outside the village must be allowed to set eyes on it. Otherwise Taitanbou’s curse will fall on the village and everyone associated.

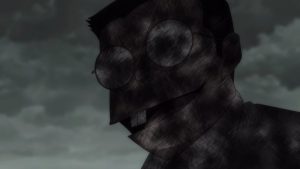

This story is about as archetypically Shinto as it gets, and Taitanbou has even popped up in earlier Kitarou incarnations several times. But damn, this particular guardian spirit is a real bastard. As a 7 year-old Kento became gravely ill merely because his father thought about trying to free him from the burden of inheriting his role as guardian, and his grandfather had to sacrifice himself to save his son and grandson. The outsider thrill-seekers who paid 10 million Yen to see (and defile – would they still have been cursed merely for looking?) paid the ultimate price (and are still paying it).

This story is about as archetypically Shinto as it gets, and Taitanbou has even popped up in earlier Kitarou incarnations several times. But damn, this particular guardian spirit is a real bastard. As a 7 year-old Kento became gravely ill merely because his father thought about trying to free him from the burden of inheriting his role as guardian, and his grandfather had to sacrifice himself to save his son and grandson. The outsider thrill-seekers who paid 10 million Yen to see (and defile – would they still have been cursed merely for looking?) paid the ultimate price (and are still paying it).

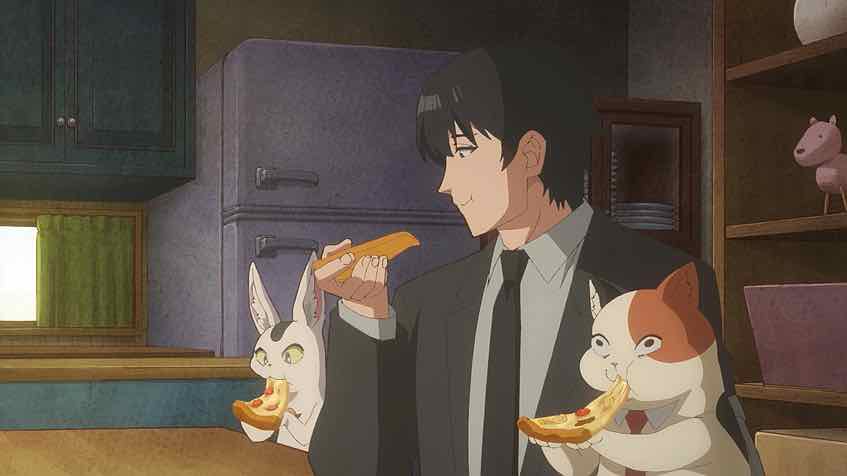

I get that Kento’s father (Tani Atsuki) brought in Team Kitarou to try and manage things. And I get that the almost-20 year-old Kento (Ono Masumi) desperately wants to be free. But the message of the ending is… odd. Basically, Taitanbou is holding Kento’s family and the entire village hostage, and Kitarou is seemingly OK with that. Certainly showing Kento (with Sunakake-Baba’s help) what would have befallen him is better than letting him be cursed, but in a way his life – and the village’s – is cursed anyway. They’re prisoners. It’s not unrealistic in terms of Shinto belief, but seems wholly out of character for the title character and the show that bears his name to accept this state of affairs.

I get that Kento’s father (Tani Atsuki) brought in Team Kitarou to try and manage things. And I get that the almost-20 year-old Kento (Ono Masumi) desperately wants to be free. But the message of the ending is… odd. Basically, Taitanbou is holding Kento’s family and the entire village hostage, and Kitarou is seemingly OK with that. Certainly showing Kento (with Sunakake-Baba’s help) what would have befallen him is better than letting him be cursed, but in a way his life – and the village’s – is cursed anyway. They’re prisoners. It’s not unrealistic in terms of Shinto belief, but seems wholly out of character for the title character and the show that bears his name to accept this state of affairs.

Robert Black

August 25, 2019 at 3:47 pmKitarou understands how the world works, and how the various cosmic balances of power operate. He stands up for the weak, but he knows his limits and he understands the concept of fate. Isn’t he “trapped” himself, in between yokai and the selfish, greedy, ungrateful humans he has to keep rescuing?

Guardian Enzo

August 25, 2019 at 4:17 pmHe still has a choice – he could choose to stop doing what he does. He’s “trapped” by his conscience, in the same way any non-sociopath is. Kento has no choice – he and his family must do what they do under threat of eternal torment. And there’s no altruistic benefit to it – only the placation of a cruel deity.