I knew something was different as soon as I saw toes.

So, I’m going to try and be a moderate on this one, because I know passions run high where Kobayashi Osamu is concerned. A confession: I liked Gurren-Lagann Episode 4 (yes, I was the one). And I loved Beck. I think anime fans since time immemorial have been way too hostile towards stylistic changes in a series, and I like experimentation. But at the same time, I get why Kobayashi is divisive (and at that, it divides probably 80% intense dislike). His style is idiosyncratic to say the least. He favors choppy cuts and lots of static shots, fuzzy background details but lots of close-ups. It’s pretty unique to say the least.

So, I’m going to try and be a moderate on this one, because I know passions run high where Kobayashi Osamu is concerned. A confession: I liked Gurren-Lagann Episode 4 (yes, I was the one). And I loved Beck. I think anime fans since time immemorial have been way too hostile towards stylistic changes in a series, and I like experimentation. But at the same time, I get why Kobayashi is divisive (and at that, it divides probably 80% intense dislike). His style is idiosyncratic to say the least. He favors choppy cuts and lots of static shots, fuzzy background details but lots of close-ups. It’s pretty unique to say the least.

Kobayashi’s signature raises an interesting question – if it makes an unaware viewer think it looks cheap, does it matter whether it actually is cheap or not? That’s the thing, Kobayashi’s aesthetic does lend itself to that misconception, there’s no denying it. And whether you like it or not, there’s the question of whether a guest director should take a series so far off its normal course in the middle of the journey, much less in the second half of a two-part storyline. It’s one thing in a show like Space Dandy, where every week featured a new vision. But Dororo has been pretty consistent up to this point.

Kobayashi’s signature raises an interesting question – if it makes an unaware viewer think it looks cheap, does it matter whether it actually is cheap or not? That’s the thing, Kobayashi’s aesthetic does lend itself to that misconception, there’s no denying it. And whether you like it or not, there’s the question of whether a guest director should take a series so far off its normal course in the middle of the journey, much less in the second half of a two-part storyline. It’s one thing in a show like Space Dandy, where every week featured a new vision. But Dororo has been pretty consistent up to this point.

Well, be that as it may, the visuals where what they were. And the episode was a cracker plot-wise, with a lot of movement on several fronts. And along with that, an ever-deeper dive into the murky moral waters in which Dororo is sailing. It’s one thing for a series to trade in shades of grey, but it’s quite unusual to get to the point (where we are now) where I’m not sure what the narrative itself believes. And we’re seeing enough tweaks from Tezuka’s original (unfinished) storyline that it’s possible the anime may land in an entirely different place in this respect.

Well, be that as it may, the visuals where what they were. And the episode was a cracker plot-wise, with a lot of movement on several fronts. And along with that, an ever-deeper dive into the murky moral waters in which Dororo is sailing. It’s one thing for a series to trade in shades of grey, but it’s quite unusual to get to the point (where we are now) where I’m not sure what the narrative itself believes. And we’re seeing enough tweaks from Tezuka’s original (unfinished) storyline that it’s possible the anime may land in an entirely different place in this respect.

Dororo and Hyakkkimaru obviously know something is very wrong in this village, but what they aren’t sure about is whether Sabame is part of that or not. Dororo investigates the village while Hyakkimaru keeps watch on Sabame, and she almost immediately gets conspiracy vibes from everyone she meets. And when she finds a lavish kura storehouse off in the woods, she becomes even more suspicious – and hopeful that it might contain treasure. But the only treasure inside is rice – and even with her seemingly hollow leg, Dororo can only eat so much rice.

Dororo and Hyakkkimaru obviously know something is very wrong in this village, but what they aren’t sure about is whether Sabame is part of that or not. Dororo investigates the village while Hyakkimaru keeps watch on Sabame, and she almost immediately gets conspiracy vibes from everyone she meets. And when she finds a lavish kura storehouse off in the woods, she becomes even more suspicious – and hopeful that it might contain treasure. But the only treasure inside is rice – and even with her seemingly hollow leg, Dororo can only eat so much rice.

Sabame doesn’t mince words with Hyakkimaru, who follows him into the woods to an overlook of the town. To say there are echoes of Daigo in his situation is an understatement – he too employs the standard consequentialist arguments to justify doing “what he has to do to save his people”. The pattern of this mythology is clear – ayakashi prey on human weakness to get what they want. But they don’t steal from their human partners, they trade with them – and they seem to honor their contracts, as far as I can tell. It’s bad enough that Sabame says what he’s done was right – what’s worse is that he probably believes it (which is why Hyakki perceives his aura the way he does).

Sabame doesn’t mince words with Hyakkimaru, who follows him into the woods to an overlook of the town. To say there are echoes of Daigo in his situation is an understatement – he too employs the standard consequentialist arguments to justify doing “what he has to do to save his people”. The pattern of this mythology is clear – ayakashi prey on human weakness to get what they want. But they don’t steal from their human partners, they trade with them – and they seem to honor their contracts, as far as I can tell. It’s bad enough that Sabame says what he’s done was right – what’s worse is that he probably believes it (which is why Hyakki perceives his aura the way he does).

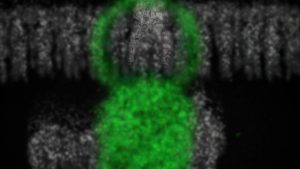

In this case the demon in question is the Maimai-onba, a giant moth who lives in the lake when she’s not being Sabame’s wife. And she does seem to have delivered peace and prosperity to the village – in exchange for the lives of the orphans at the temple, who the villagers served up to her offspring after murdering the nun in charge of them and burning the temple. Hyakkimaru eventually defeats her with fire – which seems like the right way to defeat a moth – and in the process, gets his spine back (Jukai was one hell of a doctor). This of course means that Maimai-onba wasn’t content with one deal with a corrupt human – she established a second with Sabame.

In this case the demon in question is the Maimai-onba, a giant moth who lives in the lake when she’s not being Sabame’s wife. And she does seem to have delivered peace and prosperity to the village – in exchange for the lives of the orphans at the temple, who the villagers served up to her offspring after murdering the nun in charge of them and burning the temple. Hyakkimaru eventually defeats her with fire – which seems like the right way to defeat a moth – and in the process, gets his spine back (Jukai was one hell of a doctor). This of course means that Maimai-onba wasn’t content with one deal with a corrupt human – she established a second with Sabame.

For me this isn’t all that complicated – feeding orphans to demons is not an acceptable means to save your own skin. Nor is selling your child’s body parts. But I do get why Dororo is horrified to see what becomes of the village after Maimai-onba is destroyed, and I understand why she’s angry and scared of Hyakkimaru’s single-mindedness. “Not my concern” indeed – if you were in his shoes (if he wore them) would you feel any different? Both Hyakkimaru and Dororo have been victimized – and indeed she’s at risk of it happening again, as Itashi has learned the truth of her father’s treasure map – for their entire lives.

For me this isn’t all that complicated – feeding orphans to demons is not an acceptable means to save your own skin. Nor is selling your child’s body parts. But I do get why Dororo is horrified to see what becomes of the village after Maimai-onba is destroyed, and I understand why she’s angry and scared of Hyakkimaru’s single-mindedness. “Not my concern” indeed – if you were in his shoes (if he wore them) would you feel any different? Both Hyakkimaru and Dororo have been victimized – and indeed she’s at risk of it happening again, as Itashi has learned the truth of her father’s treasure map – for their entire lives.

But now, Dororo is growing up, and forced to confront the fact that righting wrongs may in fact cause great suffering to those who bear no guilt in the matter. It’s not fair that she should be forced by her conscience to hold herself to a higher standard than those who have and continue to wrong her and Hyakkimaru. But if there’s a less fair setting than the Sengoku Period as depicted by Tezuka and Furuhashi in Dororo, you’d have a hard time convincing me of it.

But now, Dororo is growing up, and forced to confront the fact that righting wrongs may in fact cause great suffering to those who bear no guilt in the matter. It’s not fair that she should be forced by her conscience to hold herself to a higher standard than those who have and continue to wrong her and Hyakkimaru. But if there’s a less fair setting than the Sengoku Period as depicted by Tezuka and Furuhashi in Dororo, you’d have a hard time convincing me of it.

Nadavu

April 23, 2019 at 9:33 pmI don’t get why one of the moths crushed into the guard tower nor how did that cause every house in the village to suddenly errupt in flames.

Guardian Enzo

April 23, 2019 at 9:58 pmI got the idea it was kind of the same thing as Daigo’s land going to hell when parts of his contract were broken, except here the contract was just one demon so when she died, all that bad karma erupted at once.

Nadav Ornoy

April 26, 2019 at 8:34 pmCorrect me I’m wrong, though, everything started to go ablaze even before Hyakkimaru took out the queen moth at the lake. I got the impression that while Karma was definitely the reason for the village to burn down, what actually caused it was a physical chain reaction from the moth/tower collision. And It just looks lazily displayed, to me, with houses that aren’t touching each other erupting into in succession, but without the fire actually spreading from one to the other.

That point aside, I’ve been thinking a lot about the dubious morality of both sides here, and I’ve reached the conclusion that I cannot fault the villagers for doing terrible things in order to survive, but nor do I think that Hyakkimaru and Dororo should feel bad about bringing the village down. What does bother me is that neither seems to think that they should stay and help the children, at least, and basically leaving the to die of starvation and exposure. If you destroy the existing system, no matter how terrible and corrupt, you need to stay and deal with the aftermath, is what I think.

GC

April 24, 2019 at 1:18 amOther web sites are having a shark feeding frenzy over how bad this episode was quality wise. It was just awful and a step down from the usual. Some claim they are saving the budget for the next 3 part arc.

slazer

April 24, 2019 at 2:25 amEnzo – it was my understanding that Hyakkimaru saw Sabame much like he sees Daigo – a human aura with tinges of flame. The green aura that he sees seems to be him flashing back to the headless Buddha that his mother keeps in her shrine.

Mike

April 24, 2019 at 5:05 amThe art style reminded me of Masaaki Yuasa, except his stuff is wonderfully animated and this… wasn’t. It was especially jarring because it’s such a departure from the show’s immaculate ‘house’ style, so it really hurts the immersion. Weird choice to totally change the art and animation halfway through a two-parter.

I did laugh at Dororo burning down the village then blaming poor Hyakkimaru. I know the idea is that karmically the land loses its protection when the demons die, but come on Dororo, you just poured oil all over a grain store!

Guardian Enzo

April 24, 2019 at 6:42 amHeh, that is a fair point.

Ko

April 24, 2019 at 8:40 amBeyond animation, I gotta say I was a bit disappointed with the moth demon this episode. I guess I expected a bigger speaking role because of her appearance in the opening, but that really was basically nothing and kind of an anticlimactic showdown. I know it’s mostly just that I set myself up thinking it was going to be more than that, but I can’t help but feel worried that the shark guy in the opening won’t be much more than that either.

Scampi

April 24, 2019 at 1:22 pmI don’t agree with you on there being a dilemma in this situation, because the line has been crossed. With a deal once made, there is no guarantee the lord and the people wouldn’t be more greedy and sacrifice more children for their own well being. You can’t ever underestimate how prone humans are to evil, Standford prison experiment proved that. And being an Asian, I will always have a bias against Japanese consequentialism, so fuck that.

Sidenote: Rice isn’t suitable crop if you don’t have water sources, I always find it weird that Japan is so focused on rice, even to the present age. Ramen is such a modern thing in comparison.

Scampi

April 24, 2019 at 1:47 pmWith the exception of Tahomaru and mom, none have expressed any reproach of conscience. The villagers are siding with the ayakashi and not humans, the lord is regularly feeding travelers to the moths and the villagers are complicit in that. When found out they just create more victims instead of feeling guilt and fear because they did something wrong. Just reminds me of how things are still in the real world, WWII atrocities never happened for some people.

Guardian Enzo

April 24, 2019 at 1:58 pmWas that directed at me? Because I don’t think I disagreed with that in my post. Like I said, this is pretty clear-cut as far as I’m concerned. The only point I was making is that Dororo has empathy so she can’t blind herself to the fact that there are unintended consequences to actions she or Hyakkimaru might take.

Also, Japan may be short on some things (like young people) but water isn’t one of them.

Scampi

April 25, 2019 at 5:27 amIt’s more of “Dororo being confronted with moral dilemma,” because even if she’s growing up, she is still a kid, so I would rather things are more defined than the narrative makes it appears. And in this case it has been quite clear that the the village will continue to prey on innocents and such an arrangement can’t last forever. The unintended consequence side of things though, based on what happened in the very first episode I feel like she has experienced through enough worldly travails to know life is fucked in Sengoku era and not feel guilty about it, but maybe adventures with aniki has lifted her outlooks from that. To be honest Dororo is too kind and resilient for her own good, after being thrown in a dark cellar with monsters she can still empathize with the villagers, but it’s very ironic that her unintentional spilling of the oil jars contributes as much to the disaster as the intentional killing of the moth.

Japan is not an arid region but droughts can still happen. Compared to the continents where water from ice reservoirs in the mountains melt into rivers, they’re more dependent on monsoon rain, which can be finicky with natural climate oscillations. It’s also because of those rainfalls that rice is so very deeply ingrained into their culture, and I respect that, but in Dororo the contrast of water filled paddy fields next to a domain of parched land makes me wish they had better crop diversity, like grow some of those drought resistant sweet potatoes instead of going all-in with rice. At least for story purposes, the rice paddies were effective in accentuating the unnatural luxury Daigo and Sabame had obtained from the demons.

Guardian Enzo

April 25, 2019 at 11:04 amThey have actually improved in terms of crop diversity since the Meiji began (Westernization having a lot to do with that, as bread has grown steadily more popular at the expense of rice). There’s a fair amount of other grains (buckwheat, satsumaimo, jagaimo et al) grown here now. But in the Sengoku yeah, rice was indisputably king.