And lo, my pronoun nightmare is finally over.

I hope you enjoyed that brief interlude of optimism, because we’re right back in Jigoku this week on Dororo. or, as Dororo’s mom said, it’s possible that Hell would be nowhere as bad as the reality of a battlefield in the Sengoku period. When he chose to write about it, Tezuka spared no thought for the feelings of his more delicate readers when he addressed the topic of war – he hated it with every fibre of his being and he’d have been doing them a disservice by doing so. And Furuhashi-sensei and the teams at MAPPA and Tezuka Productions are following his example.

I hope you enjoyed that brief interlude of optimism, because we’re right back in Jigoku this week on Dororo. or, as Dororo’s mom said, it’s possible that Hell would be nowhere as bad as the reality of a battlefield in the Sengoku period. When he chose to write about it, Tezuka spared no thought for the feelings of his more delicate readers when he addressed the topic of war – he hated it with every fibre of his being and he’d have been doing them a disservice by doing so. And Furuhashi-sensei and the teams at MAPPA and Tezuka Productions are following his example.

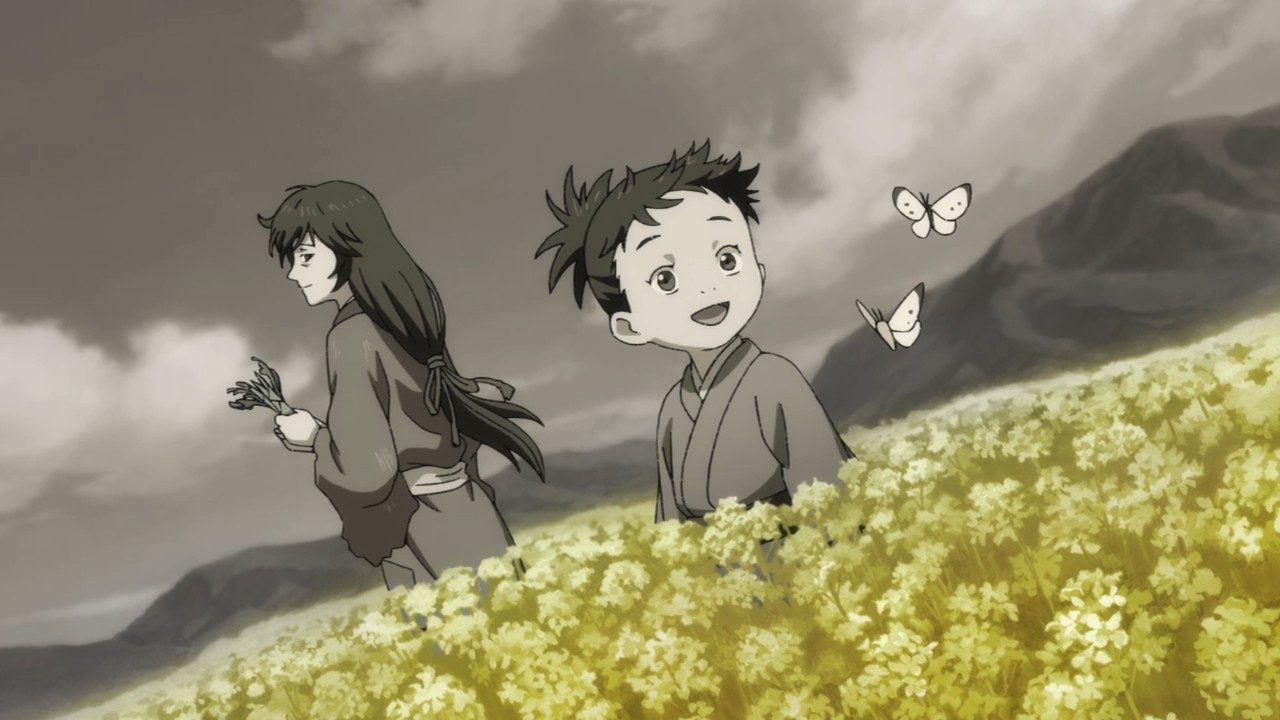

With an episode as great as this was, it’s the usual problem of not really knowing where to even start praising it. The background art, the casting, the soundtrack, the cinematography and direction – it was just a marvel on every level. Furuhashi’s decision to use mostly black-and-white for the flashback sequences is interesting, given that the original Dororo anime was broadcast in black-and-white. It’s also a marvelous way to use rare splotches of color to really create impact, as he does here – both with the lilies that Dororo has come to hate so much and the blood (most arrestingly on the face of Dororo’s father).

With an episode as great as this was, it’s the usual problem of not really knowing where to even start praising it. The background art, the casting, the soundtrack, the cinematography and direction – it was just a marvel on every level. Furuhashi’s decision to use mostly black-and-white for the flashback sequences is interesting, given that the original Dororo anime was broadcast in black-and-white. It’s also a marvelous way to use rare splotches of color to really create impact, as he does here – both with the lilies that Dororo has come to hate so much and the blood (most arrestingly on the face of Dororo’s father).

I guess I can finally say “her father” now – and frankly, it’s a relief not to keep having to use so many “they” and “Dororo” because I wasn’t sure if the anime had made it sufficiently clear that Dororo was a girl. The thing is, I really don’t think Dororo’s gender makes much of a difference, although there are obvious reasons why in this environment she’d want to keep it a secret. Dororo is who she is, girl or boy – and she’s the same tough, resilient heart and soul of the story she always was. There’s a reason Tezuka called this series “Dororo” and not “Hyakkimaru”, and that’s it – Dororo is both our lens into this world and our moral center. The 2019 anime revealed her gender long before the manga did – and the first anime never did – but for me that’s a positive, because again, her gender isn’t really the point and the longer it remains a secret, the more importance the reveal takes on.

I guess I can finally say “her father” now – and frankly, it’s a relief not to keep having to use so many “they” and “Dororo” because I wasn’t sure if the anime had made it sufficiently clear that Dororo was a girl. The thing is, I really don’t think Dororo’s gender makes much of a difference, although there are obvious reasons why in this environment she’d want to keep it a secret. Dororo is who she is, girl or boy – and she’s the same tough, resilient heart and soul of the story she always was. There’s a reason Tezuka called this series “Dororo” and not “Hyakkimaru”, and that’s it – Dororo is both our lens into this world and our moral center. The 2019 anime revealed her gender long before the manga did – and the first anime never did – but for me that’s a positive, because again, her gender isn’t really the point and the longer it remains a secret, the more importance the reveal takes on.

Dororo’s present-day story was heartbreaking enough, but when you add her history to the bonfire the pathos rages out of control. She falls ill with a fever (no anime cold, this – in this time and place illness was a matter of life and death at all times) and Hyakkimaru is desperate to try and find some help. After some callous but ultimately understandable rejections, a Buddhist nun spots the pair and lends her aid. Dororo is seeing visions of her dying mother in her delirium, and in her interludes of lucidity she’s terrified that Hyakkimaru will try and leave her behind again. But happily, there’s no danger of that – she needs to give him a little more credit for the amount of growth her influence has sparked in him.

Dororo’s present-day story was heartbreaking enough, but when you add her history to the bonfire the pathos rages out of control. She falls ill with a fever (no anime cold, this – in this time and place illness was a matter of life and death at all times) and Hyakkimaru is desperate to try and find some help. After some callous but ultimately understandable rejections, a Buddhist nun spots the pair and lends her aid. Dororo is seeing visions of her dying mother in her delirium, and in her interludes of lucidity she’s terrified that Hyakkimaru will try and leave her behind again. But happily, there’s no danger of that – she needs to give him a little more credit for the amount of growth her influence has sparked in him.

Dororo’s past comes in the form of a story to the nun (Taira Masumi, a suitably tragic name for this tale) about why she hates the red spider lilies so much (in Japan, they’re known as “death flower” because of their propensity to grow in graveyards – and they’re poisonous for good measure). Her father is Hibukuro (the great Miyake Kenta), a brigand who only targets samurai because of his resentment over their abuse of the common people. Her mother is Ojiya, played by another legend in Fujimura Ayumi – a lovely and caring woman who clearly believes in the cause but wishes her husband would step back from the brink of destruction.

Dororo’s past comes in the form of a story to the nun (Taira Masumi, a suitably tragic name for this tale) about why she hates the red spider lilies so much (in Japan, they’re known as “death flower” because of their propensity to grow in graveyards – and they’re poisonous for good measure). Her father is Hibukuro (the great Miyake Kenta), a brigand who only targets samurai because of his resentment over their abuse of the common people. Her mother is Ojiya, played by another legend in Fujimura Ayumi – a lovely and caring woman who clearly believes in the cause but wishes her husband would step back from the brink of destruction.

Those two are wonderful, but remarkably they’re upstaged by the performance of the less-known Setsuji Satoh, who plays Hibukuro’s second-in-command, Itachi. Itachi is the really interesting one here, a smart and brutally honest man who sees the writing on the wall for Hibukuro’s band. He’s the cause of Hibukuro’s downfall and ultimately, his death and that of Ojiya – but it’s too easy to casually condemn him for what he does. He chooses not to throw his life away, just as Mio did, compromising his ideals in the process – if Hibukuro had made that choice, Dororo wouldn’t be an orphan. Itachi chose to parlay the success of the group into a deal with the local lord. Others made the choice to become what came to be known as the Ikkou-ikki, autonomous bands of peasants, monks and ronin who defied the daimyo and eventually became quite powerful in Japan – but that’s a topic for its own post, at the very least…

Those two are wonderful, but remarkably they’re upstaged by the performance of the less-known Setsuji Satoh, who plays Hibukuro’s second-in-command, Itachi. Itachi is the really interesting one here, a smart and brutally honest man who sees the writing on the wall for Hibukuro’s band. He’s the cause of Hibukuro’s downfall and ultimately, his death and that of Ojiya – but it’s too easy to casually condemn him for what he does. He chooses not to throw his life away, just as Mio did, compromising his ideals in the process – if Hibukuro had made that choice, Dororo wouldn’t be an orphan. Itachi chose to parlay the success of the group into a deal with the local lord. Others made the choice to become what came to be known as the Ikkou-ikki, autonomous bands of peasants, monks and ronin who defied the daimyo and eventually became quite powerful in Japan – but that’s a topic for its own post, at the very least…

One can make too much of symbolism, but Tezuka was fiercely anti-war and it colored much of what he did – he was lucky in barely missing out on fighting in World War II because of his age, but he certainly saw its effects first-hand. I do believe he’s asking a larger question not just through this episode, but throughout Dororo – is it better to die with honor, or to compromise and live? No one could deny that Hibukuro died an honorable death, but he left his wife and child behind, and she died to save their daughter – but not before one of the most gut-wrenching scenes in anime this year, where she shows her devotion by accepting boiling gruel for Dororo in her bare hands.

One can make too much of symbolism, but Tezuka was fiercely anti-war and it colored much of what he did – he was lucky in barely missing out on fighting in World War II because of his age, but he certainly saw its effects first-hand. I do believe he’s asking a larger question not just through this episode, but throughout Dororo – is it better to die with honor, or to compromise and live? No one could deny that Hibukuro died an honorable death, but he left his wife and child behind, and she died to save their daughter – but not before one of the most gut-wrenching scenes in anime this year, where she shows her devotion by accepting boiling gruel for Dororo in her bare hands.

This is what evil does – it forces good people to make impossible decisions with no right answers, and that’s the tragedy at the heart of Dororo. Because she refused to give up (as her mother begged) Dororo lived – and she survives her fever too, to continue on with Hyakkimaru with the truth revealed. Meanwhile Daigo (and Tahoumaru) are inching closer to the truth of Hyakkimaru’s existence, Dororo’s act of restraining Hyakkimaru before he could finish off the commander of the troops who killed Mio and her orphans providing a big push. Like splashes of red in a monochrome palette, there are islands of kindness and grace in this hell Tezuka has depicted – but are they enough to give real hope?

This is what evil does – it forces good people to make impossible decisions with no right answers, and that’s the tragedy at the heart of Dororo. Because she refused to give up (as her mother begged) Dororo lived – and she survives her fever too, to continue on with Hyakkimaru with the truth revealed. Meanwhile Daigo (and Tahoumaru) are inching closer to the truth of Hyakkimaru’s existence, Dororo’s act of restraining Hyakkimaru before he could finish off the commander of the troops who killed Mio and her orphans providing a big push. Like splashes of red in a monochrome palette, there are islands of kindness and grace in this hell Tezuka has depicted – but are they enough to give real hope?

Miyu Fan

March 5, 2019 at 8:59 pmMaybe it’s the lack of my knowledge of Japanese history, but I’m a bit confused on the purpose of Dororo’s father bands of farmers attacking the samurai. Do they continue to just attack every samurai they encountered during the way? That’s why to me Itachi isn’t that completely evil, in the end you have to think about your future. And killing the samurai really doesn’t make Dororo’s father right either. Really love the complexity of the characters in this show.

Guardian Enzo

March 5, 2019 at 9:25 pmGoogle the Ikkou-ikki – that gives you a sense of what groups like this were trying to accomplish (and for a while, did).

Kawaki

March 5, 2019 at 11:35 pmThe main reason why they attacked the samurai was that they were part of the reason why their land was damaged, and many people had lost their families and homes. Before the scene where Dororo’s father gets brutally killed, the samurai burn down the village, and because of situations like that do the brigands have a strong will to fight back against them.

A.Sade

March 5, 2019 at 11:47 pmYou’ve read the manga and watched the old anime, Enzo? I was under the impression that you were fresh to the series.

I was spoiled about Dororo’s gender by a random YouTube comment but I just had to get my fill of Dororo content and an anime episode a week just wasn’t enough. I actually started reading the manga a while back but I held off once I reached Dororo’s backstory because I wanted to see how the anime does it first. As expected, it was amazing. The red amidst the monochrome was really reminiscent of my film classes about Schlinder’s List haha

Guardian Enzo

March 6, 2019 at 8:37 amI have not, but have absorbed some info by osmosis over the years (and I too was spoiled about Dororo’s gender, I don’t even remember where).

leongsh

March 6, 2019 at 12:48 amYour last line may need to be reconsidered – this part, “this hell Tezuka has created”. That period of time was that kind of hell, i.e. he “recreated” how the Sengoku was like.

Other than that, the write-up is one I substantially have and agree with.

Snowball

March 6, 2019 at 2:23 amI suspected that Dororo was a girl since episode 2 when Hyakkimaru clasped her face in his hands and she blushed. However, I also agree that the gender doesn’t really change the essence of the character.

On another note, I remember my time living in Japan, not fluent in Japanese, and speaking using only key words like Hyakkimaru.

Guardian Enzo

March 6, 2019 at 8:38 amIt’s hard to say how obvious the gender has or hasn’t been, since I knew. It feels like it’s been pretty obvious but that could be confirmation bias.

Snowball

March 6, 2019 at 3:57 pmI think reading from a lot of comments on streaming sites, it wasn’t obvious. I came into this anime quite fresh and thought Dororo was a boy, only episode 2 gave me a hint that it was otherwise.