I’ve been putting this one off for a bit, to be honest. I was pretty sure this finale was going to lay me out big-time (it did), so I wanted to wait until I had a chunk of time to really absorb it. Golden Week seemed like the right opportunity, so here we are. We’re talking about an ongoing manga of course, so I wasn’t expecting a conclusive ending in the strictest sense. But given the nature of the story any ending was going to have a kick. And in this case, with steel-toed boots.

I’ve been putting this one off for a bit, to be honest. I was pretty sure this finale was going to lay me out big-time (it did), so I wanted to wait until I had a chunk of time to really absorb it. Golden Week seemed like the right opportunity, so here we are. We’re talking about an ongoing manga of course, so I wasn’t expecting a conclusive ending in the strictest sense. But given the nature of the story any ending was going to have a kick. And in this case, with steel-toed boots.

What makes this last episode stand out for me is tone. In a word, it was very restrained. And that restraint added to the emotional impact. That restraint is overall one of Kotarou wa Hitorigurashi’s secret weapons, a vital reason why it doesn’t slide into melodrama territory. But the final ep heeds a key lesson narrative drama teaches – the more emotionally loaded a situation is, the less you should try and sell it. Pathos is self-perpetuating – it doesn’t need embellishment. And in terms of pathos, this premise is pretty much off the charts.

What makes this last episode stand out for me is tone. In a word, it was very restrained. And that restraint added to the emotional impact. That restraint is overall one of Kotarou wa Hitorigurashi’s secret weapons, a vital reason why it doesn’t slide into melodrama territory. But the final ep heeds a key lesson narrative drama teaches – the more emotionally loaded a situation is, the less you should try and sell it. Pathos is self-perpetuating – it doesn’t need embellishment. And in terms of pathos, this premise is pretty much off the charts.

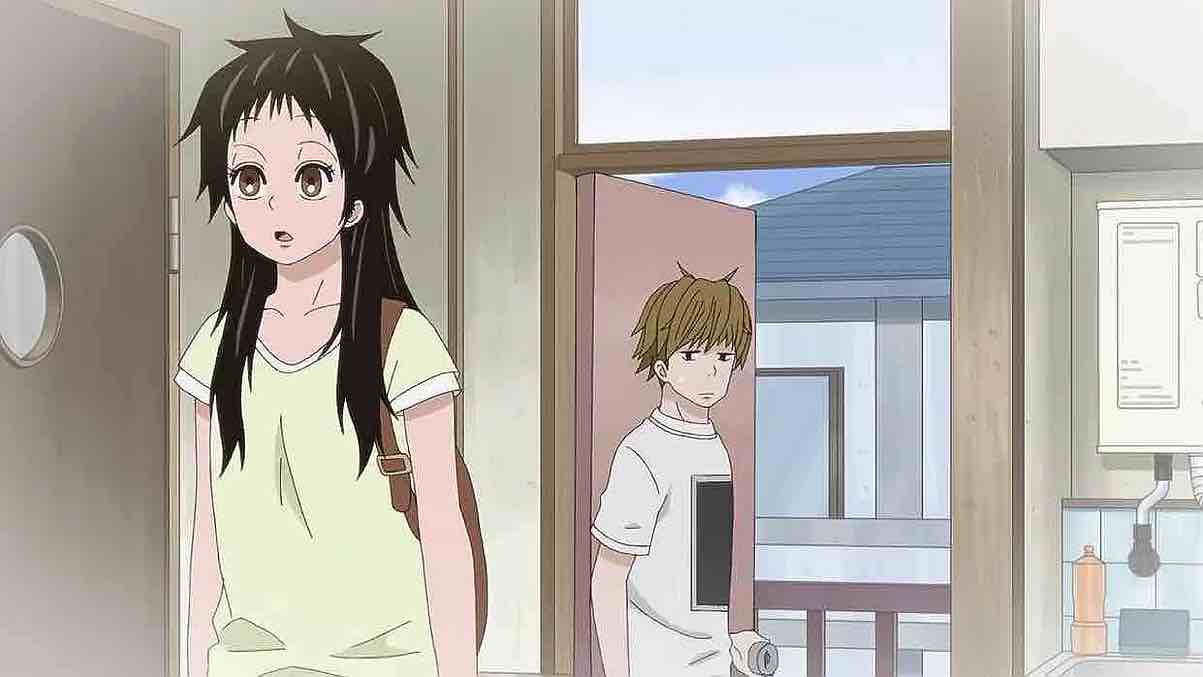

There are milestone events occurring throughout the story, as you’d expect. For Karino-san, his one-shot is being picked up for a short serialization – with the potential for more. Old girlfriend Akane (Lynn) has crashed at his apartment, and when she sees him doing all-nighters she takes it on herself to take Kotarou off his hands. She means well, but this is why you don’t butt in when you don’t understand the dynamics of the situation. Karino is doing this for Kotarou-kun at this point – which I think says an awful lot. Does it make sense for him to rely on some help for a while until the crush slows down? Sure. But he’s not asking to be relieved of duty.

There are milestone events occurring throughout the story, as you’d expect. For Karino-san, his one-shot is being picked up for a short serialization – with the potential for more. Old girlfriend Akane (Lynn) has crashed at his apartment, and when she sees him doing all-nighters she takes it on herself to take Kotarou off his hands. She means well, but this is why you don’t butt in when you don’t understand the dynamics of the situation. Karino is doing this for Kotarou-kun at this point – which I think says an awful lot. Does it make sense for him to rely on some help for a while until the crush slows down? Sure. But he’s not asking to be relieved of duty.

Make no mistake, the relationship between Shin and Kotarou is the heart of Kotarou Lives Alone. It is restrained – we’ve never seen them hug. Karino never tells Kotarou he loves him, or vice-versa (they’re boys, after all). But that doesn’t mean it isn’t the case. Clearly, this has stopped being a burden for Shin and become a chosen vocation. The most impressive thing for me is that he remembered Kotarou’s “entertainment day” (I’ve been to those at Japanese KG, and they’re pretty damn adorable). But he didn’t make a big deal about it – he even lied to Akane about remembering. He just showed up at the recital, because not doing so would never have been a consideration.

Make no mistake, the relationship between Shin and Kotarou is the heart of Kotarou Lives Alone. It is restrained – we’ve never seen them hug. Karino never tells Kotarou he loves him, or vice-versa (they’re boys, after all). But that doesn’t mean it isn’t the case. Clearly, this has stopped being a burden for Shin and become a chosen vocation. The most impressive thing for me is that he remembered Kotarou’s “entertainment day” (I’ve been to those at Japanese KG, and they’re pretty damn adorable). But he didn’t make a big deal about it – he even lied to Akane about remembering. He just showed up at the recital, because not doing so would never have been a consideration.

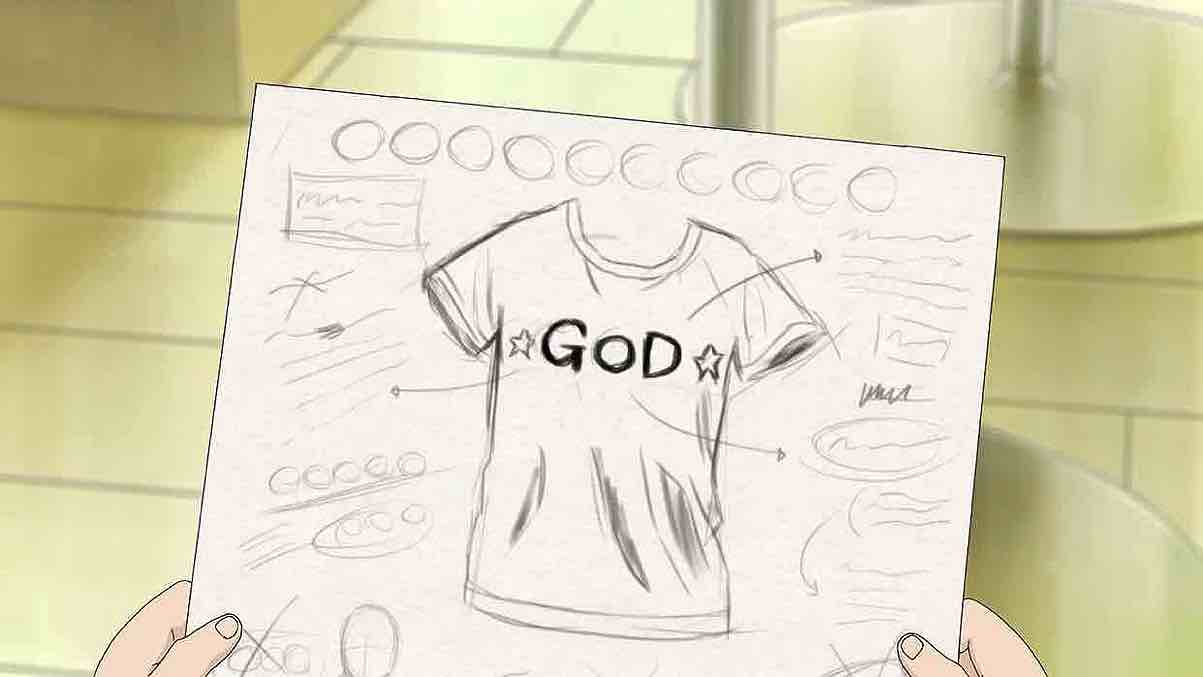

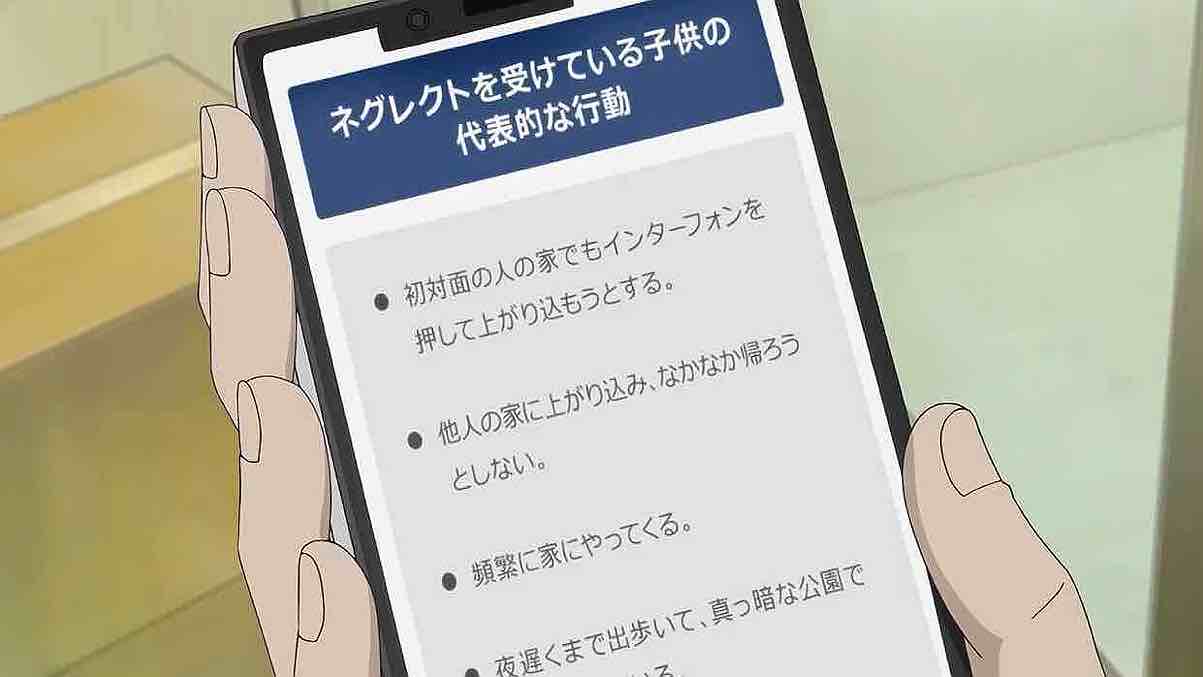

I’d been wondering what the deal with the “God” shirts was, so I was happy the show decided to explain that. Kotarou’s former neighbor was Tamamori-san (he’s played by Nishiyama Koutarou, who in addition to the name coincidence played Ryuuichi in Gakuen Babysitters, probably the closest series to this one in tone), a clothing designer. In those days Kotarou was reduced to ringing random doorbells for someone to talk to – which the clueless Tamamori’s friend explains to him is basically a cry for help from latchkey kids. But they don’t even know the half of it.

I’d been wondering what the deal with the “God” shirts was, so I was happy the show decided to explain that. Kotarou’s former neighbor was Tamamori-san (he’s played by Nishiyama Koutarou, who in addition to the name coincidence played Ryuuichi in Gakuen Babysitters, probably the closest series to this one in tone), a clothing designer. In those days Kotarou was reduced to ringing random doorbells for someone to talk to – which the clueless Tamamori’s friend explains to him is basically a cry for help from latchkey kids. But they don’t even know the half of it.

I’m guessing the newspaper chapter also takes place before Kotarou meets up with Karino-san, though it’s not made crystal clear. That one hit hard on so many levels. We have Kotarou subscribing to no less than five morning newspapers, for multiple reasons. First of all he scans them for news of his parents. It’s also, clearly, another excuse to steal some human interaction. But finally, he asks the kind-hearted delivery guy to watch his door in case the papers start piling up, because that would be a sign something had happened to him. I’m not sure any four-year old would ever think about that, but I sure as hell know none should ever have to.

I’m guessing the newspaper chapter also takes place before Kotarou meets up with Karino-san, though it’s not made crystal clear. That one hit hard on so many levels. We have Kotarou subscribing to no less than five morning newspapers, for multiple reasons. First of all he scans them for news of his parents. It’s also, clearly, another excuse to steal some human interaction. But finally, he asks the kind-hearted delivery guy to watch his door in case the papers start piling up, because that would be a sign something had happened to him. I’m not sure any four-year old would ever think about that, but I sure as hell know none should ever have to.

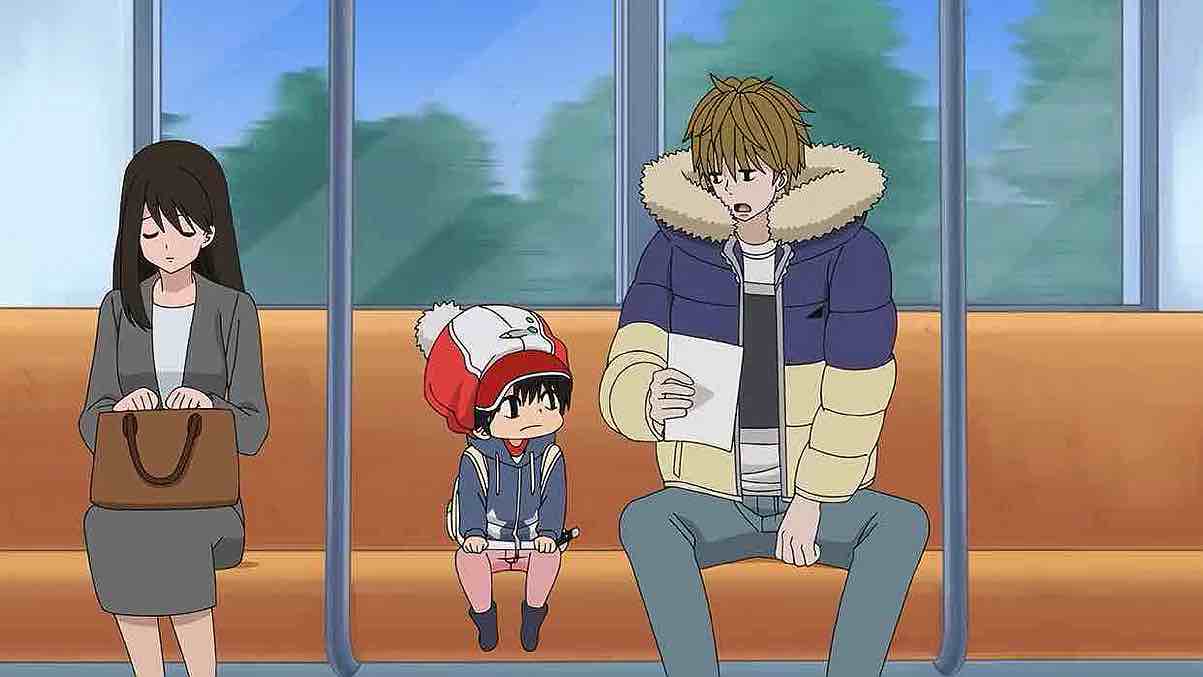

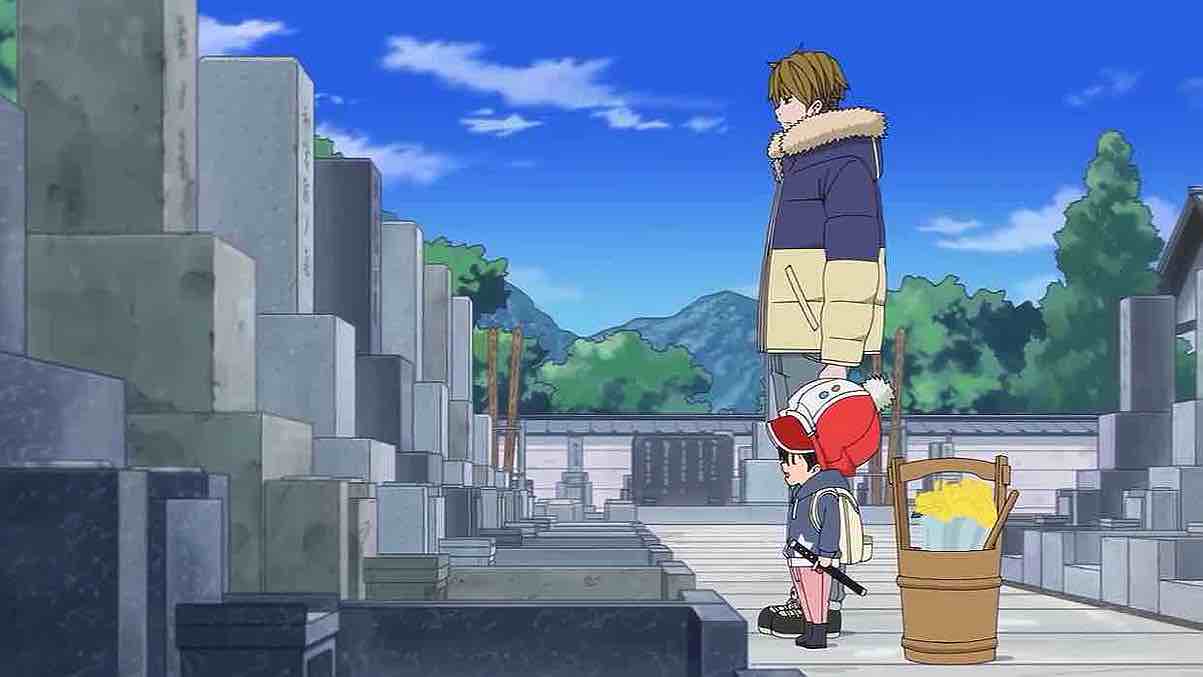

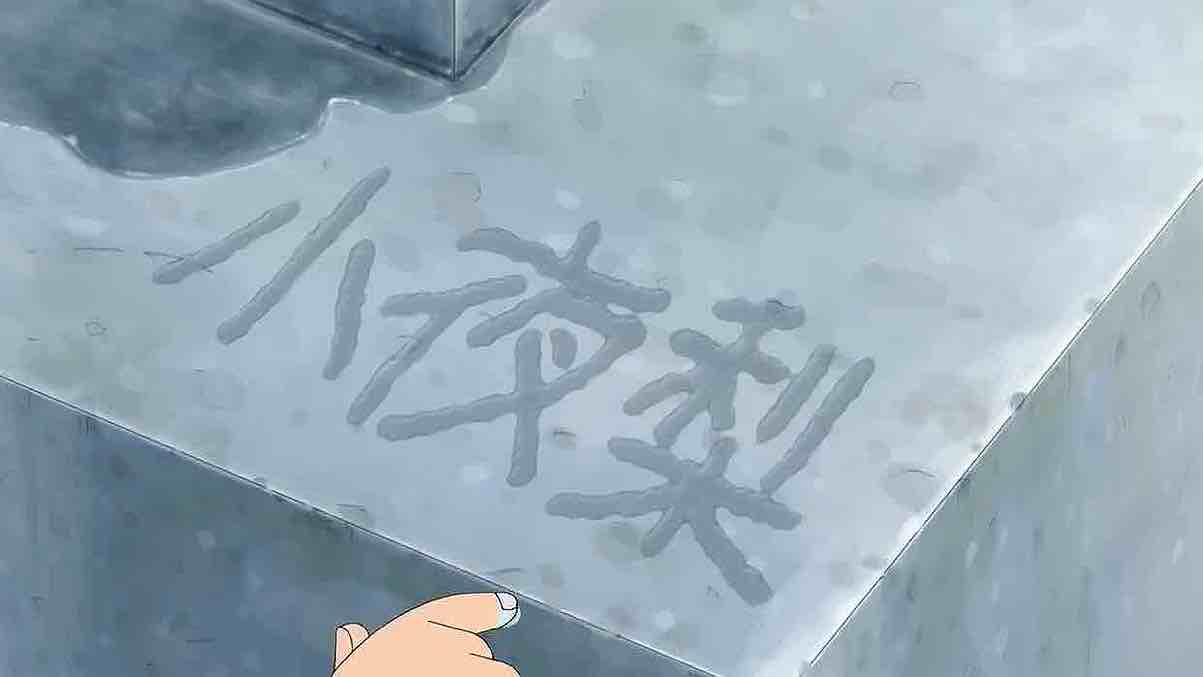

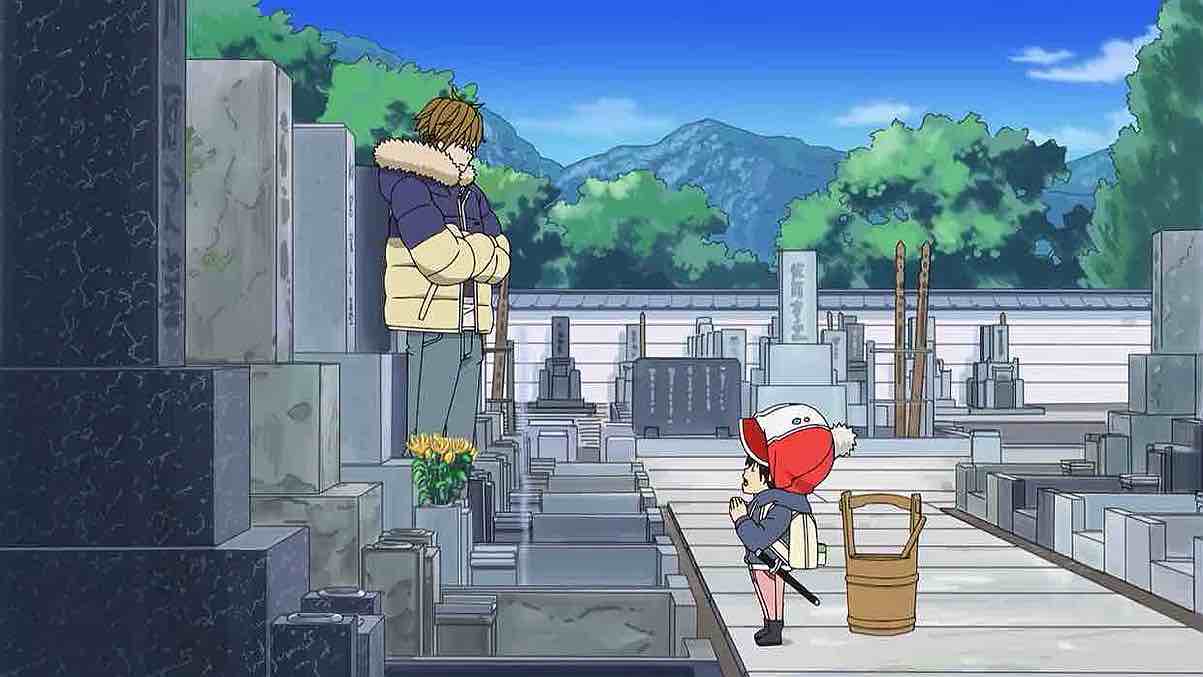

Of course the final chapter should be the most brutal of all – I’d expect nothing else. After hearing a familiar station name on TV, Kotarou decides he wants to try and find the cemetery where his maternal grandparents are buried – a place he’s visited but once. He’s prepared to go alone but I think he knows Shin will never allow that. Kotarou gets pretty surly when Karino-san oversleeps, but they find their destination. Kotarou has never even met these people, but they represent a connection he wants to keep alive. The problem comes when Shin sees Kotarou’s mother’s name on the marker next to her parents.

Of course the final chapter should be the most brutal of all – I’d expect nothing else. After hearing a familiar station name on TV, Kotarou decides he wants to try and find the cemetery where his maternal grandparents are buried – a place he’s visited but once. He’s prepared to go alone but I think he knows Shin will never allow that. Kotarou gets pretty surly when Karino-san oversleeps, but they find their destination. Kotarou has never even met these people, but they represent a connection he wants to keep alive. The problem comes when Shin sees Kotarou’s mother’s name on the marker next to her parents.

The question here, I suppose, is whether Shin did the right thing in hiding the truth from (okay, lying to) Kotarou. After all, he’s just assured the boy that “lying isn’t my thing”. Is it better for Kotarou to be spared the truth, and to hold out hope for something that can never happen? I won’t pretend to be wise enough to know the answer. But Kotarou is only five, for all his old soul character traits. In Shin’s position I’d probably have done the same thing, because you just don’t know how Kotarou would react to the truth. In a sense this is a selfless act by Shin, because he knows Kotarou will blame him for lying when he does (inevitably) find out the truth. But raising children is all about selfless acts – which is why so many people are so bad at it.

The question here, I suppose, is whether Shin did the right thing in hiding the truth from (okay, lying to) Kotarou. After all, he’s just assured the boy that “lying isn’t my thing”. Is it better for Kotarou to be spared the truth, and to hold out hope for something that can never happen? I won’t pretend to be wise enough to know the answer. But Kotarou is only five, for all his old soul character traits. In Shin’s position I’d probably have done the same thing, because you just don’t know how Kotarou would react to the truth. In a sense this is a selfless act by Shin, because he knows Kotarou will blame him for lying when he does (inevitably) find out the truth. But raising children is all about selfless acts – which is why so many people are so bad at it.

I think, in watching this series, the next logical step seems obvious. Surely Kotarou should just live with Karino-san – be adopted by him, presuming the authorities would sign off. But their current arrangement allows Kotarou to live in his fantasy world to an extent, which I suppose is the point. Shin certainly wouldn’t be (isn’t) a perfect parent. But he cares, which in the end is surely the single most important thing. Kotarou wa Hitorigurashi is a depressing series in many ways. It chronicles just about every way individual adults and society as a whole can fail children. Sometimes actively, but mostly passively – looking the other way, not being present.

I think, in watching this series, the next logical step seems obvious. Surely Kotarou should just live with Karino-san – be adopted by him, presuming the authorities would sign off. But their current arrangement allows Kotarou to live in his fantasy world to an extent, which I suppose is the point. Shin certainly wouldn’t be (isn’t) a perfect parent. But he cares, which in the end is surely the single most important thing. Kotarou wa Hitorigurashi is a depressing series in many ways. It chronicles just about every way individual adults and society as a whole can fail children. Sometimes actively, but mostly passively – looking the other way, not being present.

This is the real irony here. All of the adults who have a moral and legal responsibility to look after Kotarou fail him. It’s the ones who do so almost entirely by choice – most obviously Shin – who are his salvation. As depressing as the larger premise is, that’s actually kind of uplifting. All in all that sums up this wonderful show well – depressing but kind of uplifting. The production as a whole is simple, even spartan – but that just assists in letting the situation speak for itself. The cast is excellent, with a special nod to Kugimiya Rie for one of the most nuanced and powerful performances of her career.

This is the real irony here. All of the adults who have a moral and legal responsibility to look after Kotarou fail him. It’s the ones who do so almost entirely by choice – most obviously Shin – who are his salvation. As depressing as the larger premise is, that’s actually kind of uplifting. All in all that sums up this wonderful show well – depressing but kind of uplifting. The production as a whole is simple, even spartan – but that just assists in letting the situation speak for itself. The cast is excellent, with a special nod to Kugimiya Rie for one of the most nuanced and powerful performances of her career.

We’re only in May, and Netflix already has two series which are going to be strong contenders for the year-end Top 10 list (and almost certainly on it, unless the rest of 2022 is astonishingly good). That’s encouraging – they’re definitely getting better at this. Their recent financial troubles and news of cancelled projects (including in animation) cast the future of Netflix anime in doubt. It comes at the worst possible time, because the industry needs shows like this and Chikyuugai Shounen Shoujo more than ever. Kotarou wa Hitorigurashi reminds us of what should be obvious, but is all too often forgotten. And of what we take for granted, and never should.

We’re only in May, and Netflix already has two series which are going to be strong contenders for the year-end Top 10 list (and almost certainly on it, unless the rest of 2022 is astonishingly good). That’s encouraging – they’re definitely getting better at this. Their recent financial troubles and news of cancelled projects (including in animation) cast the future of Netflix anime in doubt. It comes at the worst possible time, because the industry needs shows like this and Chikyuugai Shounen Shoujo more than ever. Kotarou wa Hitorigurashi reminds us of what should be obvious, but is all too often forgotten. And of what we take for granted, and never should.

Marty

May 5, 2022 at 8:25 amGoddamn, this series hits hard. Children are a whole ass commitment, and to be fair, it takes a fair bit of self-reflection to acknowledge if a person is truly ready for one.

Guardian Enzo

May 5, 2022 at 9:06 pmWhich is why this is sort of interesting. None of the people in Shimizu Apartments made a conscious decision to get involved with a child, so presumably (certainly not Shin) none of them ever really asked this question. And superficially Shin is certainly not someone most people would say is remotely ready to raise a child. Yet somehow he managed to make the cut, simply because he defaulted to being a decent person.

Rob Barrett

May 6, 2022 at 3:19 amReading your review, I notice that it is very dusty indeed in my house.

Guardian Enzo

May 6, 2022 at 6:39 amDamned allergies.