I love and hate writing about Seirei no Moribito, because I love the show itself so much. My respect and love for this story and its characters is profound – it wormed its way into my consciousness from the first episodes and will forever be a significant part of who I am. Hell, I’ve written well over 100,000 words about this series counting analysis and fiction, just trying to satisfy its intellectual and emotional hold on me. But I know I can add nothing to the experience, and it frustrates me – that these episodes are better left to speak for themselves.

I love and hate writing about Seirei no Moribito, because I love the show itself so much. My respect and love for this story and its characters is profound – it wormed its way into my consciousness from the first episodes and will forever be a significant part of who I am. Hell, I’ve written well over 100,000 words about this series counting analysis and fiction, just trying to satisfy its intellectual and emotional hold on me. But I know I can add nothing to the experience, and it frustrates me – that these episodes are better left to speak for themselves.

It’s striking how many sequences in Moribito I could (and probably have) say this about, but this episode contains what may be the best five minutes in anime. Most of the time with narrative fiction, even if its good, there’s a layer of remove from reality that makes our perception of the emotions portrayed a bit fuzzy. Not with Moribito – they ring with crystal clarity, like a bell on a cold and windless morning. It can be overpowering at times, at least for me. And this episode is so dense with emotional heft that I find myself replaying certain scenes over, just to really consider the words that are being said.

It’s striking how many sequences in Moribito I could (and probably have) say this about, but this episode contains what may be the best five minutes in anime. Most of the time with narrative fiction, even if its good, there’s a layer of remove from reality that makes our perception of the emotions portrayed a bit fuzzy. Not with Moribito – they ring with crystal clarity, like a bell on a cold and windless morning. It can be overpowering at times, at least for me. And this episode is so dense with emotional heft that I find myself replaying certain scenes over, just to really consider the words that are being said.

Even as the central drama of a narrative and not the supporting theme of the supporting theme as it is here, Jiguro’s tale would be profound and tragic. This is the weight Balsa has borne all her life from the moment the two of them fled Kanbal, and the full crushing impact of it bore down on her after Jiguro killed the remaining King’s Spears. Balsa knew by then just how profoundly Jiguro was destroyed by this – she even tried to separate herself from him (she was sixteen by then) in the aftermath. But this was wrong – Jiguro was not a man capable of openly expressing love, but his tepid declaration of affection for Balsa was a veritable soliloquy for him. He gave up everything for her – to give up her too would have been the final act of cruelty at the hands of fate.

Even as the central drama of a narrative and not the supporting theme of the supporting theme as it is here, Jiguro’s tale would be profound and tragic. This is the weight Balsa has borne all her life from the moment the two of them fled Kanbal, and the full crushing impact of it bore down on her after Jiguro killed the remaining King’s Spears. Balsa knew by then just how profoundly Jiguro was destroyed by this – she even tried to separate herself from him (she was sixteen by then) in the aftermath. But this was wrong – Jiguro was not a man capable of openly expressing love, but his tepid declaration of affection for Balsa was a veritable soliloquy for him. He gave up everything for her – to give up her too would have been the final act of cruelty at the hands of fate.

Ultimately, Jiguro’s part of the story and indeed the story itself come down to the power of empathy as a source for good. As Balsa came to realize, Jiguro gave up everything for her because to be able to help someone in need and not do so would be an evil act. As Burke said, “The only thing necessary for the triumph of evil is for good men to do nothing.” Jiguro was, unquestionably, a good man – and he acted. Balsa is, unquestionably, a good woman. Like Jiguro, she struggles to express her feelings and erects an emotional wall around herself. Like him, she’s done things in the name of good that she deeply regrets. But when fate has called on her to act, she acted. And like Jiguro, for Balsa an act of duty grew into love.

Ultimately, Jiguro’s part of the story and indeed the story itself come down to the power of empathy as a source for good. As Balsa came to realize, Jiguro gave up everything for her because to be able to help someone in need and not do so would be an evil act. As Burke said, “The only thing necessary for the triumph of evil is for good men to do nothing.” Jiguro was, unquestionably, a good man – and he acted. Balsa is, unquestionably, a good woman. Like Jiguro, she struggles to express her feelings and erects an emotional wall around herself. Like him, she’s done things in the name of good that she deeply regrets. But when fate has called on her to act, she acted. And like Jiguro, for Balsa an act of duty grew into love.

To the end, Jiguro tried to protect Balsa from Fate, in the beginning by refusing to train her in combat. He tried to tell her she need feel no debt to him, and to help her understand just what she was committing herself to when she promised to save lives for each of the ones he took for her. But this was her penance, for the cost her life incurred for others. And in her bond with Chagum, Balsa comes to finally understand Jiguro – what he was feeling during the time he spent with her, and what drove him to behave in ways she couldn’t understand at the time. Empathy, as always, is the key.

To the end, Jiguro tried to protect Balsa from Fate, in the beginning by refusing to train her in combat. He tried to tell her she need feel no debt to him, and to help her understand just what she was committing herself to when she promised to save lives for each of the ones he took for her. But this was her penance, for the cost her life incurred for others. And in her bond with Chagum, Balsa comes to finally understand Jiguro – what he was feeling during the time he spent with her, and what drove him to behave in ways she couldn’t understand at the time. Empathy, as always, is the key.

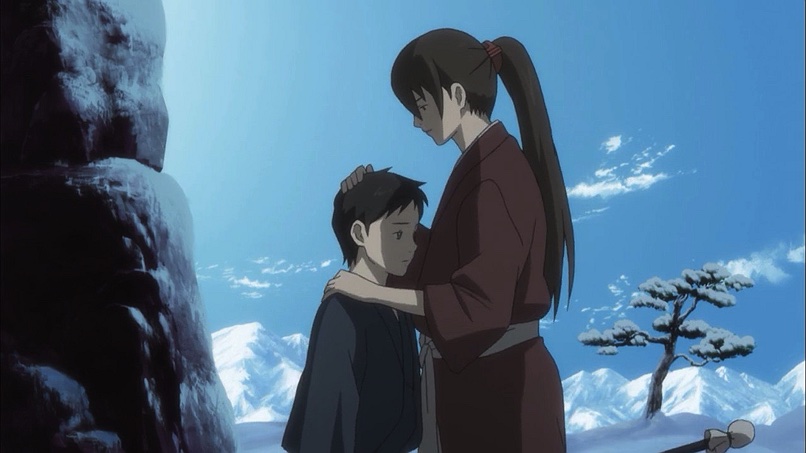

I don’t think there’s ever been an embrace more profound and significant in anime than that between Balsa and Chagum here. Because of how much meaning was expressed in the moment, because of all that had built up to it, because of everything that was yet to come. And I don’t think there’s ever been a better sequence than the five minutes or so that began there, and was followed by the montage of Balsa training Chagum as Kawai Kenji’s impossibly beautiful “Nahji no Uta” played in the background. It speaks more in the absence of dialogue than garden-variety series do in their entire run.

I don’t think there’s ever been an embrace more profound and significant in anime than that between Balsa and Chagum here. Because of how much meaning was expressed in the moment, because of all that had built up to it, because of everything that was yet to come. And I don’t think there’s ever been a better sequence than the five minutes or so that began there, and was followed by the montage of Balsa training Chagum as Kawai Kenji’s impossibly beautiful “Nahji no Uta” played in the background. It speaks more in the absence of dialogue than garden-variety series do in their entire run.

Tanda is, as is so often the case, the silent observer here. Torogai has fled to the onsen rather than subject herself to the open expression of familial love that has grown at Hunter’s Cave (because she’s feeling it herself). Tanda’s eyes speak volumes without words too, but words he does have – after treating Chagum’s wounds and observing Balsa as she watches over him sleeping, he finally says what’s been unsaid for all the time we’ve known him. He wants to share his life with Balsa, and now with Chagum too. If all that had come for weren’t enough – and it was more than enough for ten anime episodes – this bomb Tanda drops is the coup de grâce.

Tanda is, as is so often the case, the silent observer here. Torogai has fled to the onsen rather than subject herself to the open expression of familial love that has grown at Hunter’s Cave (because she’s feeling it herself). Tanda’s eyes speak volumes without words too, but words he does have – after treating Chagum’s wounds and observing Balsa as she watches over him sleeping, he finally says what’s been unsaid for all the time we’ve known him. He wants to share his life with Balsa, and now with Chagum too. If all that had come for weren’t enough – and it was more than enough for ten anime episodes – this bomb Tanda drops is the coup de grâce.

“If you can’t believe I could be that medicine, I guess there’s no point in me waiting”. If anything sums up the tragedy of Tanda’s life, that expression of futility (which Chagum overhears) does. Tanda is a safe and sheltered port to tie up to, and Balsa is someone who can’t bring herself to be anchored. Tanda complements Balsa in almost every sense, yet the two of them are fundamentally incompatible as a couple. Not even their shared love for Chagum – and his for them – can change that. People are who they are, and the only one we have the power to change is ourselves.

“If you can’t believe I could be that medicine, I guess there’s no point in me waiting”. If anything sums up the tragedy of Tanda’s life, that expression of futility (which Chagum overhears) does. Tanda is a safe and sheltered port to tie up to, and Balsa is someone who can’t bring herself to be anchored. Tanda complements Balsa in almost every sense, yet the two of them are fundamentally incompatible as a couple. Not even their shared love for Chagum – and his for them – can change that. People are who they are, and the only one we have the power to change is ourselves.

This interlude at Hunter’s Cave is one of the very best passages in Seirei no Moribito, and I can’t help but imagine that most lesser writer-directors would have blown through it in ten minutes or skipped it altogether (it’s barely a blip in the novel). That Kamiyama Kenji didn’t is the essence of why this series is is a masterpiece, and not just a success. But that winter in the cave is a respite, no more – and with the approach of spring come harsh reminders of what’s ahead for these characters. No matter how much we want the dream to go on forever, in the end it’s just that, a dream. And the only option open to these three beautiful souls is to face reality head-on, no matter how painful it promises to be.

This interlude at Hunter’s Cave is one of the very best passages in Seirei no Moribito, and I can’t help but imagine that most lesser writer-directors would have blown through it in ten minutes or skipped it altogether (it’s barely a blip in the novel). That Kamiyama Kenji didn’t is the essence of why this series is is a masterpiece, and not just a success. But that winter in the cave is a respite, no more – and with the approach of spring come harsh reminders of what’s ahead for these characters. No matter how much we want the dream to go on forever, in the end it’s just that, a dream. And the only option open to these three beautiful souls is to face reality head-on, no matter how painful it promises to be.

Panino Manino

August 3, 2020 at 2:45 amTanda is the most tragic character of them all.

Can’t beat the shot magic old man…