OP: “Kaijuu (怪獣)” by Sakanaction (サカナクション

Before we begin, a partial list of the awards Chi.: Chikyuu no Undou ni Tsuite has racked up in manga form:

- Tezuka Award 2023 (won)

- Seiun Award 2023 (won)

- Manga Taisho 2021 (2nd)

- Manga Taisho 2022 (5th)

- Kono Manga ga Sugoi 2022 (2nd)

In short, the manga is one of the most critically acclaimed titles of the decade. It’s also finished at 8 volumes and 62 chapters, which means Madhouse should be able to adapt it in the scheduled 25 episodes without extensive cuts. Director Shimizu Kenichi is one of the bigger names at the studio, having worked on the likes of Kiseijuu. And in Sakamoto Maaya it has one of the best seiyuu in the business in the lead role. All systems would certainly seem to be go, then.

But despite all that, I went into this premiere with a certain level of trepidation. Simply put, I dropped the manga after 20 chapters or so. It was undeniably very interesting, but it just didn’t click with me. The art by mangaka Uoto was certainly a part of that – I found their character designs especially kind of off-putting. The thing is, with a manga you can never tell how much of a problem the art is when the art is a problem. Did it undercut my enjoyment of the series in other ways, subliminally? It’s hard to know. It’s rare for me to drop a manga primarily because of the art, so I’m not sure exactly why it didn’t work for me here. But for whatever reason, it didn’t.

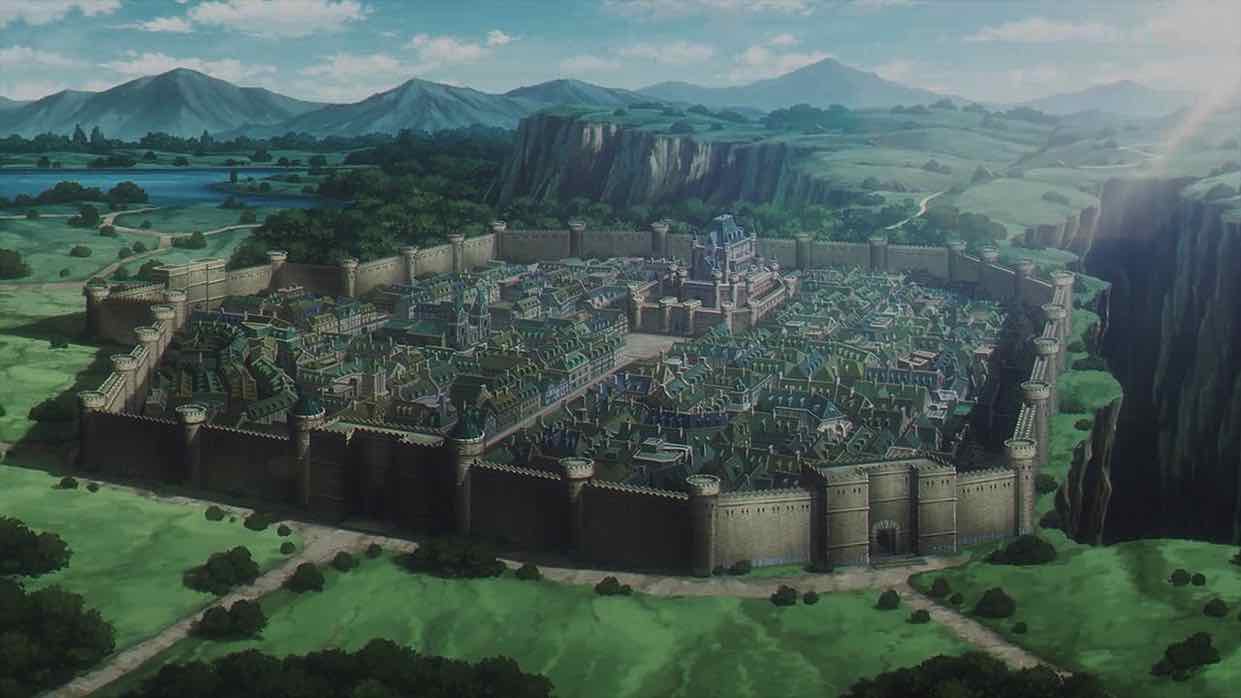

My hope was that by whatever means – Madhouse “fixing” the art or just the general sensory change in experiencing the material in this form – the anime would complete the circuit in a way the manga could not. And so far, the returns are extremely positive. This was the best premiere of the season so far, really engaging from start to finish. Madhouse has a way of “Madwashing” visuals – to an extent, all their shows share a look. That can be a positive or a negative but it’s mostly the former for me here. The backgrounds are really lovely here – the depiction of 15th-Century Poland is vibrant and immersive.

In a season driven by “serious” stories, Chi Chikyuu is arguably the most serious. Its subject is the persecution of heretics in medieval Poland (it’s not named here but calling it “P” and a cast with more -skis than Aspen at Christmas doesn’t exactly hide it) by the Catholic Church. Men like Copernicus were trying to cut through the mythology of the Church and explain the laws the Universe. The Church was trying to stop them at any cost. Most everyone has heard of the Spanish Inquisition but there was a Polish Inquisition too, aimed mainly at heretics in academia. And astronomy was right in its crosshairs.

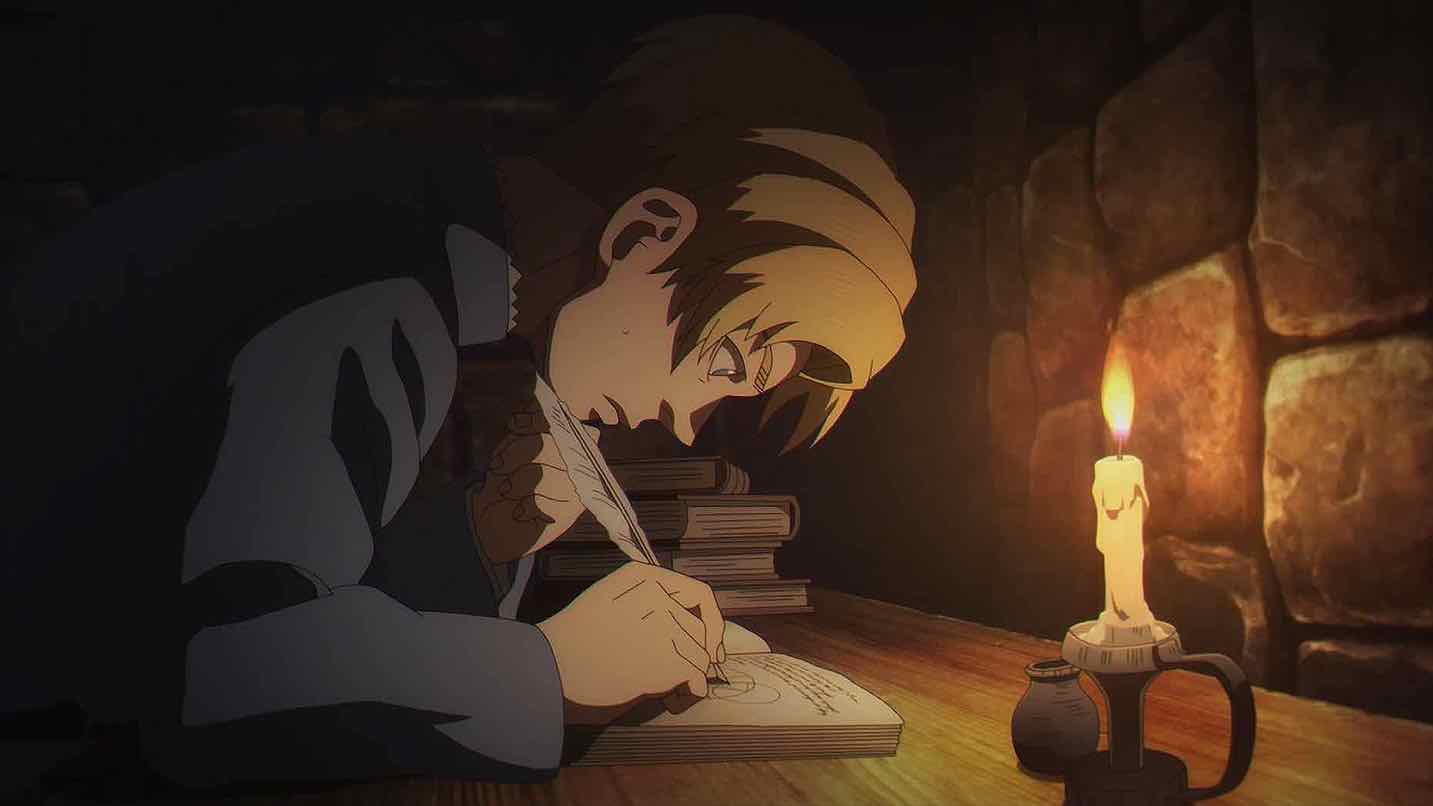

As it happens Copernicus rose to prominence rather late in this game, on the backs of others tortured and killed for espousing many of the same ideas. He was also very clever when it came to politics and good at avoiding trouble (for the most part). The focus of Chi Chikyuu is the period before Copernicus, where the idea of a Heliocentric universe was just starting to take hold among students of astronomy. The protagonist is a 12 year-old named Rafal, an orphan taken in by the local schoolteacher who proves to be a prodigy at school. For his efforts he’s granted the rare honor of attending university, where he promises his guardian that he’ll study theology.

Rafal is indeed a clever boy, one who thinks he’s figured out the key to a good life and manipulating people. It must be said, Sakamoto Maaya – always superb – has a particular genius at this sort of character. Cat-like little boys smart enough to get into a lot of trouble. Rafal is determined to check the right boxes for a life of comfort, but he’s burdened with a keen intellect and a love of rationality. That’s why he loves observing the stars – an activity his guardian scolds him that he must abandon immediately. Rafal’s life changes radically when his guardian dispatches him to collect a recanted heretic, Hubert (Hayami Show), taken in as a gesture of forgiveness.

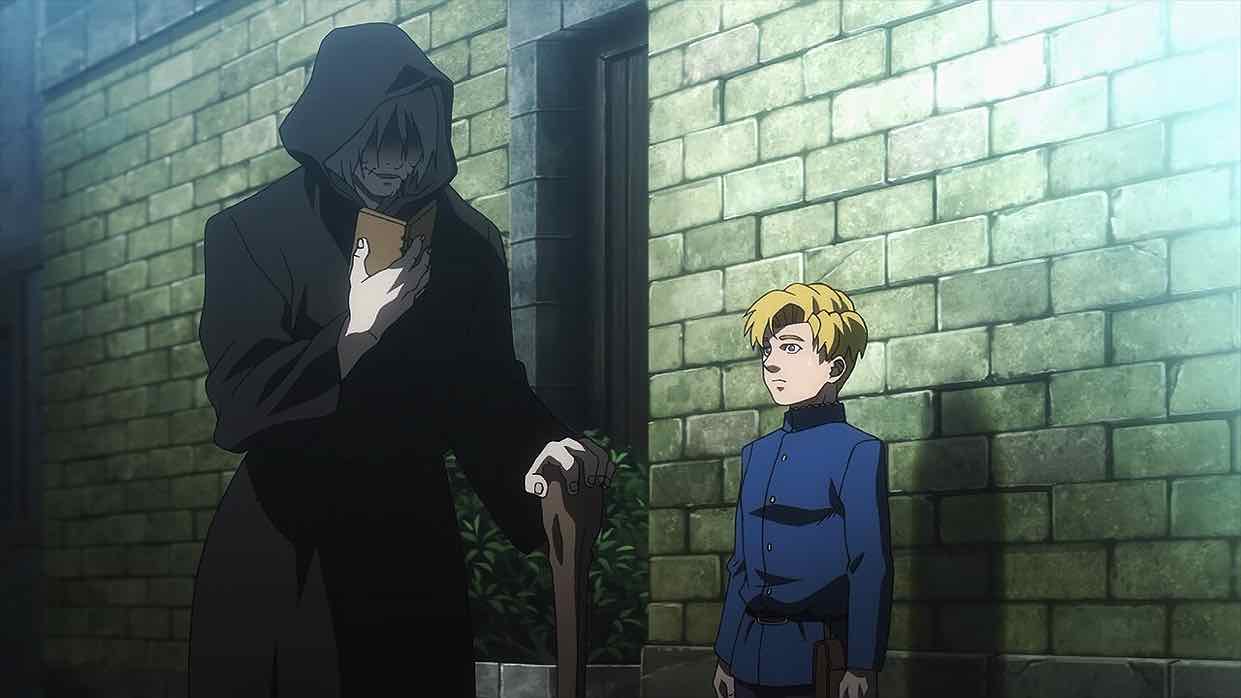

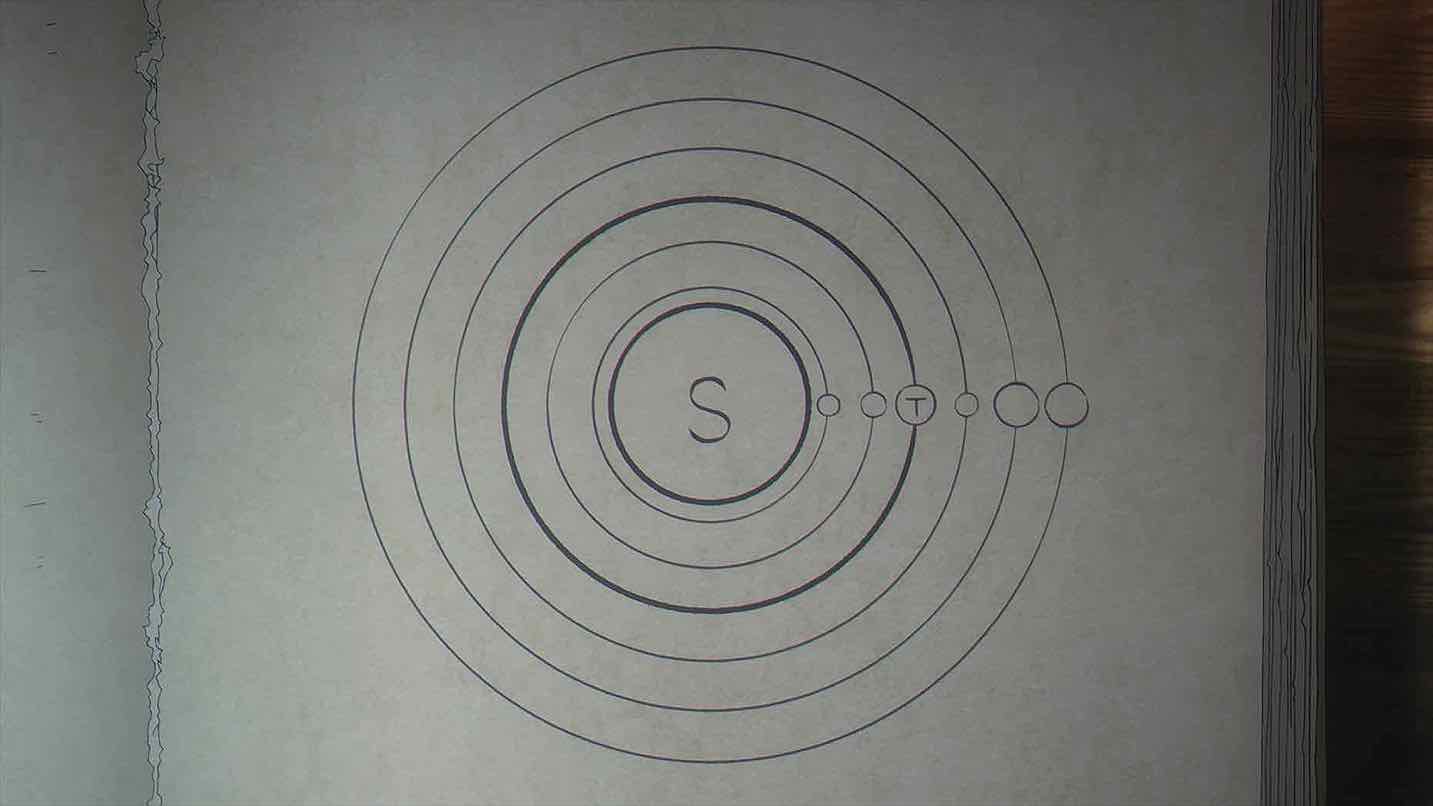

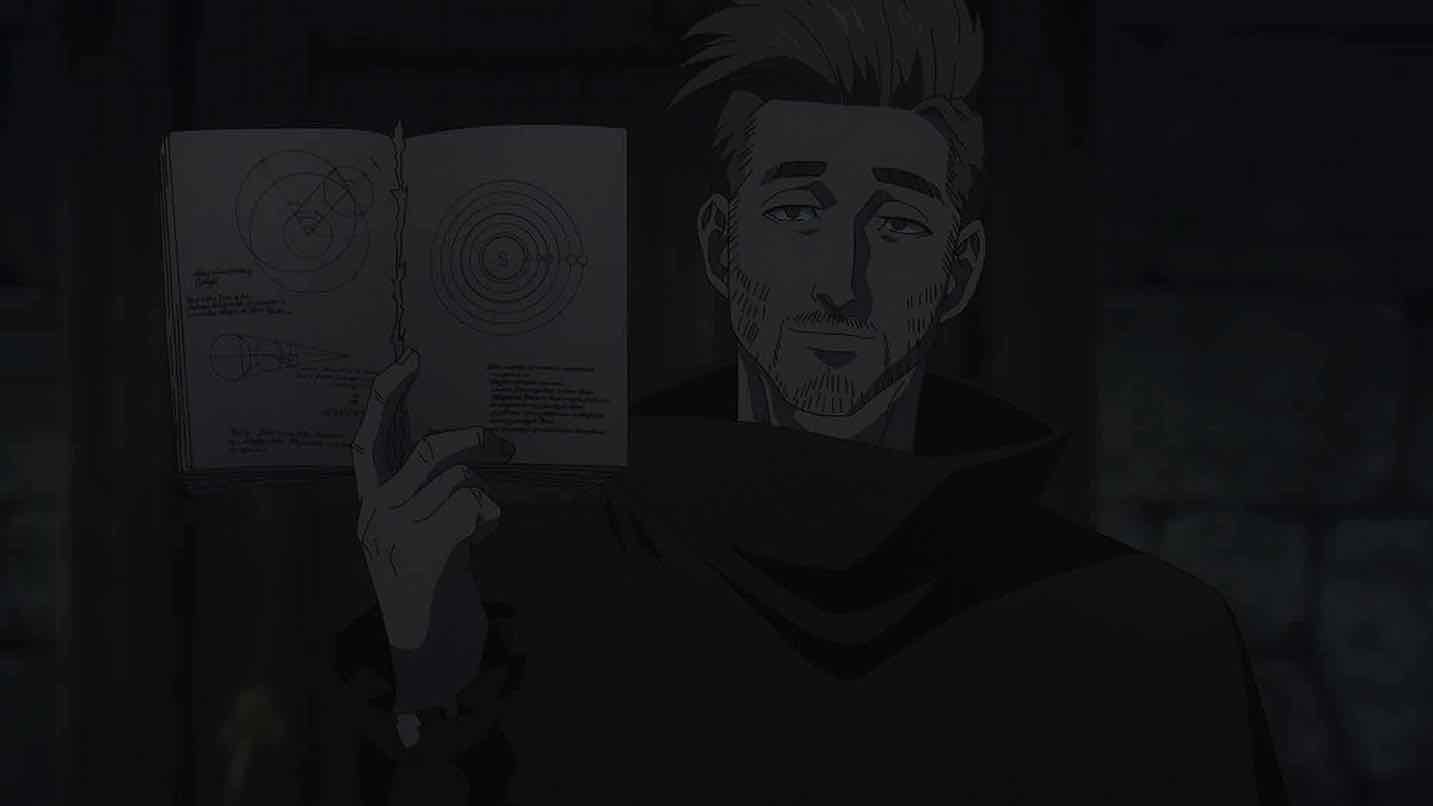

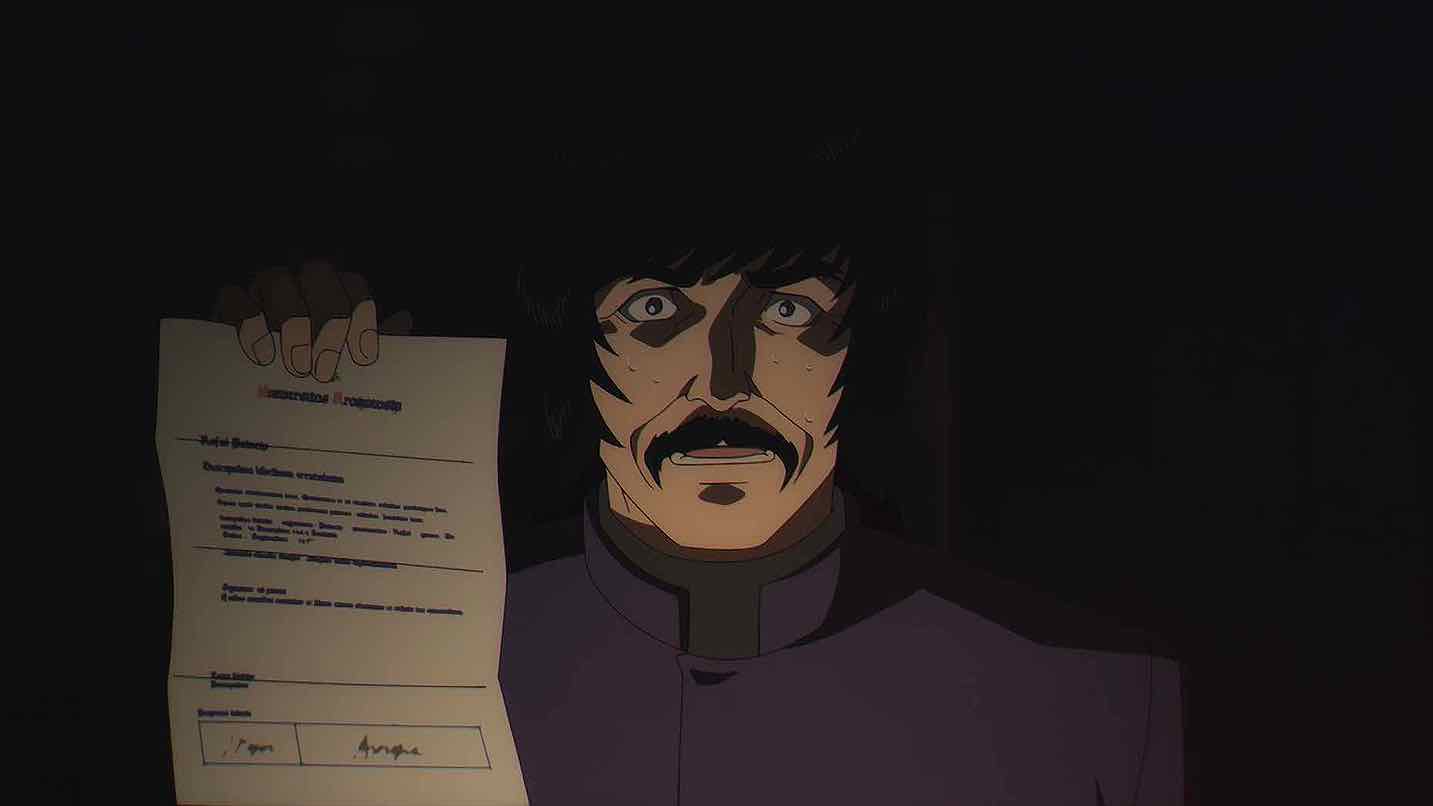

Hubert, as it turns out, has recanted in word only and has no intention of abandoning the research that got him branded as a heretic. And he immediately spots Rafal’s astrolabe and observation notebook, correctly assessing him to be a budding astronomer. He immediately proceeds to blackmail the lad into helping him with his research, his own eyes being not what they were and his body wracked by years of torture. Rafal is indignant at anyone having the gall to rock his boat, but he’s also intrigued at the idea of seriously researching the universe in secret (while realizing, I think, the peril that involves).

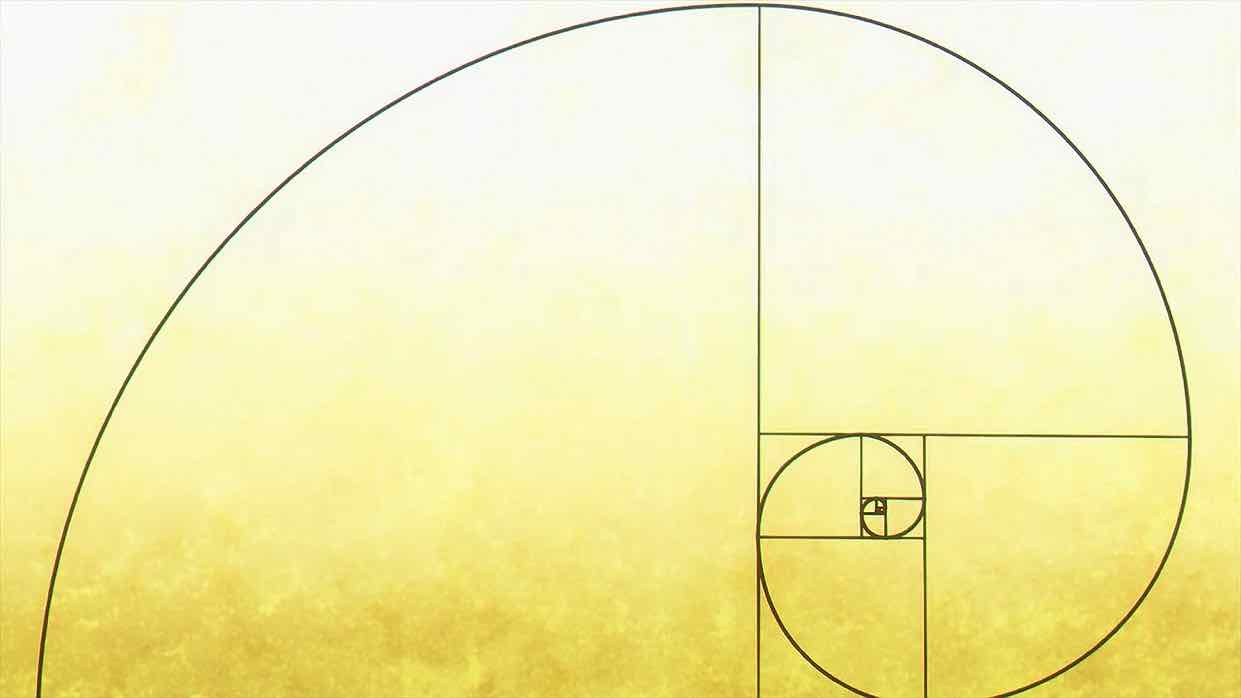

The discussion man and boy have regarding rationality and beauty is the most interesting of the season, to be sure. Hubert lays a trap for Rafal, smart but inexperienced. By getting him to admit that the geocentric model approved by the church was not beautiful because it’s not rational, Hubert makes it impossible for Rafal to ever accept it – that would eat away at him intolerably. The Heliocentric model first proposed by Aristarchus in ancient Greece is difficult to grasp, but once grasped elegant in a way the old beliefs are not. Because it reflects the truth, and not a lie.

All this is playing out in an environment where torture and heretics being burned at the stake are just a part of Rafal’s daily life. We meet one of the inquisitors, a man named Nowak (Tsuda Kenjirou – nice to see him finally get some work). It’s not immediately clear whether he’s merely professional about it or actually enjoys his job. But it seems very obvious that he’s not bothered by the nature of it – it’s what he does, and he aims to do it efficiently. And in this setting, he’ll never wont for opportunities to practice his craft.

There are so many deep ideas being traded in here that it would be easy to get bogged down in an Algonquin Roundtable-style discussion of them. But you can’t talk about this series without acknowledging that it is, at heart, both academic and philosophical as much as entertainment for its own sake. The mind of an intelligent child truly is a wondrous thing – that may be the central conceit of On the Movements of the Earth (at least the early parts) as much as anything, Rafal is such a child, one who until Hubert came into his life had little idea how incomplete his world view was. Hubert did him the service of opening his eyes to that, but in the process made him a heretic in a world of inquisitors.

Rafal’s rebuttals to Hubert’s theories – and worldview – are logical in their way. Hubert can’t defend either without calling on intuition. But he’s also awakening the boy’s intuition in the process. Heliocentrism isn’t logical according to the accepted model Rafal grew up with. Hubert can’t prove it – that’s where intuition comes in. But how different is that from faith, really? The God Hubert believes in would never create a world that was dark and ugly merely as a staging ground for the afterlife. It would be elegant and beautiful, as Heliocentrism is. And once the seed of doubt is planted Rafal can’t suppress his doubts. He knows, intuitively, that what Hubert says is true.

Hubert has placed a terrible burden on Rafal, no question. The world is indeed full of fools, as the lad says, even as he acknowledges that following the path he’s chosen makes him one himself. Ignorance is indeed bliss, especially in this environment. But Hubert, knowing he can’t prove his theories himself, takes the fall when Rafal’s naïveté makes him careless and his notebook is found by Nowak. Hubert has already placed the burden of the truth on Rafal’s thin shoulders; now he places the responsibility of finishing what he started on top of it.

In order for what either this man or this boy choose to do to make sense, one has to believe that there is beauty in truth. You can bring God into it or not, it works either way – but without that core belief, it collapses like a house of cards. Rafal, in the way of brilliant kids since time immemorial, is full of mistakes but with an endless capacity to learn from them, and quickly. Declaring his intention to study astronomy to his father is a blunder, and untenable. Lying about it is so much easier – a lie to serve a larger truth. In Rafal’s sharp but unformed mind it makes sense – only as he matures will he understand the costs attached to taking that approach.

The world is full of mysteries and contradictions. A devout man who detests heretics living in a house full of astronomy books. An inquisitor for the Church not of the Church, a soldier with a wife and child. A planet that moves constantly while appearing to be perfectly still. To a brilliant young mind like Rafal’s contradictions are irresistible puzzles. But his world is fraught with peril – an inquisition focused on stamping out the inquisitive. This a fascinating story which poses questions defying easy answers, and a unicorn in the world of anime. If these two brilliant episodes are anything to go on, Chi.: Chikyuu no Undou ni Tsuite may have found the ideal vehicle to tell that story.

ED: “Aporia (アポリア)” by Yorushika (ヨルシカ

Snowball

October 6, 2024 at 9:07 pmI was on the edge of my seat throughout this great 2-episode premiere. The atmosphere was appropriately intense, the torture scenes really brutal, yet the wonders of nature were beautifully depicted. You’ve got to love a series that challenges the mind.

Joshua

October 6, 2024 at 10:16 pmMuch like Pluto a year prior, Netflix grabbing this show is probably one of the biggest Ws that they’ve ever got in the anime sphere. Getting this one prestige series that will absolutely get all the deserved acclaim from critics for its writing and characters all while CR is stuck with more sequels and isekai shows this fall. DunMeshi after all was one of the most popular and talked about shows all year and that was locked to Netflix globally. And now they have the show that will get major awards and acclaim from critics.

Which then makes me sad that this will probably get overshadowed by the likes of Blue Box, Dandadan and Ranma (which were promoted significantly more, the latter which will get more turnout thanks to nostalgia alone).

Panino Manino

October 7, 2024 at 12:46 amI don’t care about the awards, I’ll stay away from this like I did from the mangá because I know it’ll make me made with it’s “historical representation”.

Red

October 8, 2024 at 10:01 amI might have glossed this over in the fall preview but I’m glad you’ve covered this, Enzo. I’ve been a fan of astronomy since childhood and your comment on this series with Vinland saga made me watch it. By the end of the 2nd episode, that 5-7 min. of watching certain series were back. Thank you.

I’ll also leave this quote here which seems to come to mind while watching, though I can’t seem to remember the author: “Expand your mind to the vastness of the universe, not confine the universe to the narrowness of the mind.”

Guardian Enzo

October 8, 2024 at 10:35 amWell said, whoever it was.

I’m bemused by some of the criticism I see this series getting over so-called historical accuracy, but I think that’s a topic better addressed in the next post.