The wheel of fate moves quickly. On the fourth episode we already get a ten-year timeskip. We bid Do widzenia to a legendary protagonist (he certainly went out in style) and welcome a (mostly) new cast of characters. But this is still a story rooted in the same themes – truth, beauty, belief and institutions vs. belief in one’s own truth. And in the historical sense, ten years is not a very long time – this setting is still Poland in the early 15th Century, and in practical terms not that much has changed.

Though I expressed my intent not to wade into the historical accuracy quicksand after last week, I will say that I have no idea if the notion of professional duelists was a thing in medieval Poland. I know dueling has a long history in the “P Kingdom”, and this does seem like the sort of thing you’d see – rich cowards paying professional mercenaries to fight their duels for them. But if it was widespread there’s not much evidence of it – there are a few scattered references to the practice in Europe but details are very sketchy. Best to chalk it up to dramatic license.

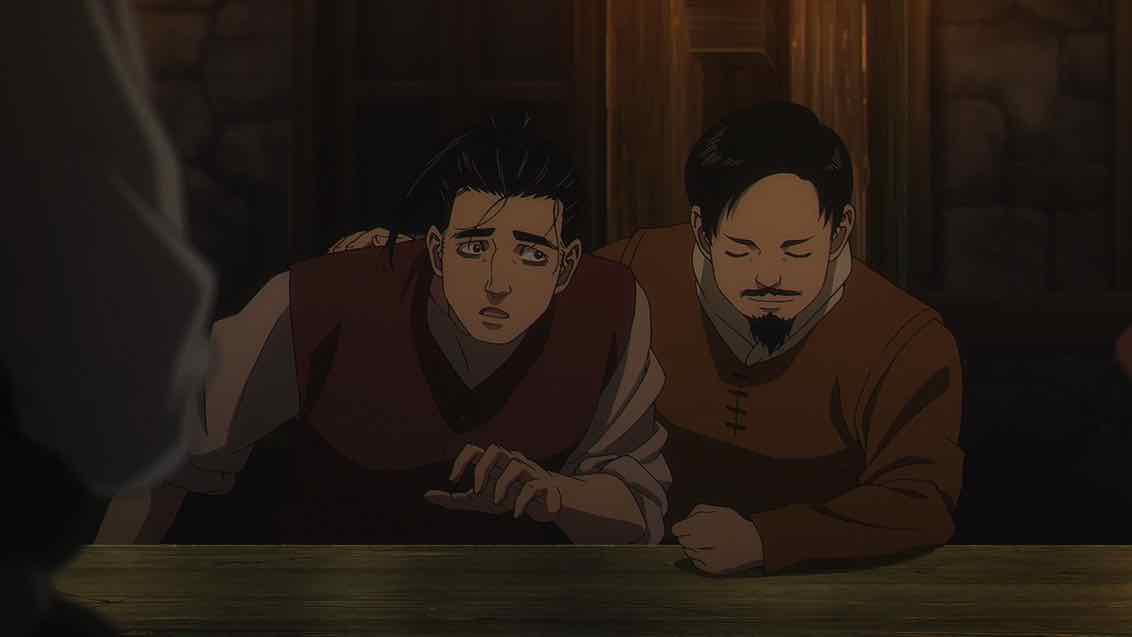

Effectively mercenaries is what Oczy (Konishi Katsuyuki) and Gras (Shiraishi Minoru) are. Every night they fulfil their duties in the “Civilian Guard”, most of the time by taking the place of a nobleman in a duel and killing the opponent. These are men of the lower classes, but not without introspection. Oczy is wracked with guilt over what he does. He sees the terror in mens’ eyes as they die, not the look of someone about to ascend to Heaven. And of course as their killer, how can he expect to ascend himself? Gras is cheerful, and spends his free time gazing up at the skies and observing the movements of the stars (and not just the stars).

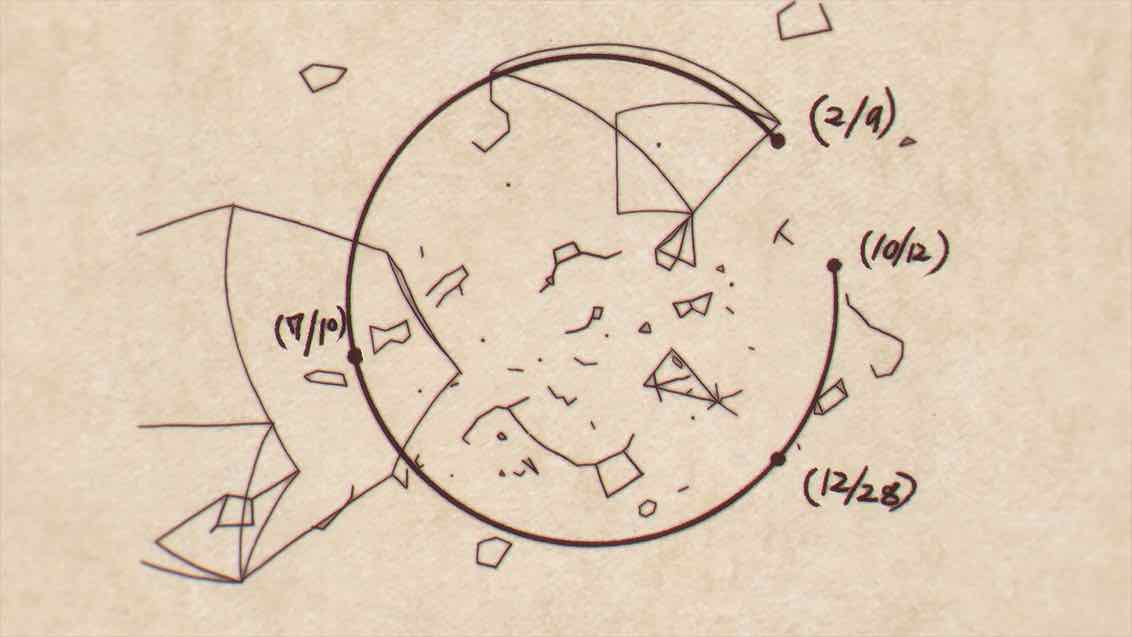

These are obviously existential questions that observe no boundaries of time. Gras seems to have found meaning, a way of coping he’s eager to share with his partner. He tells the reluctant Oczy of how he observed one “star” moving independently of the others, a fiery red orb a monk would later tell him was Mars – one of about five celestial objects called “planets”. He tracks it for two years as it seems to make a perfect orbit across the sky, a process which is just about to complete itself. A snarky noble in a tavern hints that Gras is pursuing a dead end, but declines to engage in a full scientific debate with a peasant (and a mercenary at that).

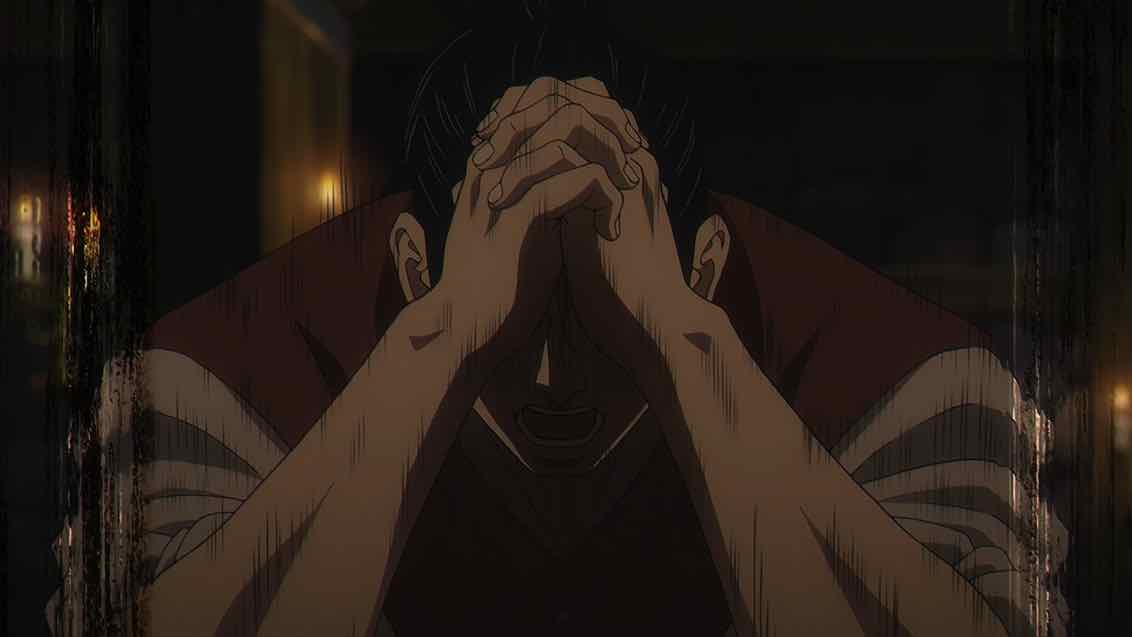

As it turns out Gras has lost his entire family to the plague. Worse, he tried to commit suicide – the gravest of all sins – and survived. It was only through the movement of the Heavens that he escaped his pit of despair, seeing the symmetry of it as a message from his family. Oczy is unmoved and unconvinced, but plays along. For him the world is such an unspeakably vile and unjust place that it’s only the belief in Heaven that keeps him going. If there’s no Heaven what’s the point of all the suffering on Earth (this is getting right at the heart of the fundamental debate about religion, of course).

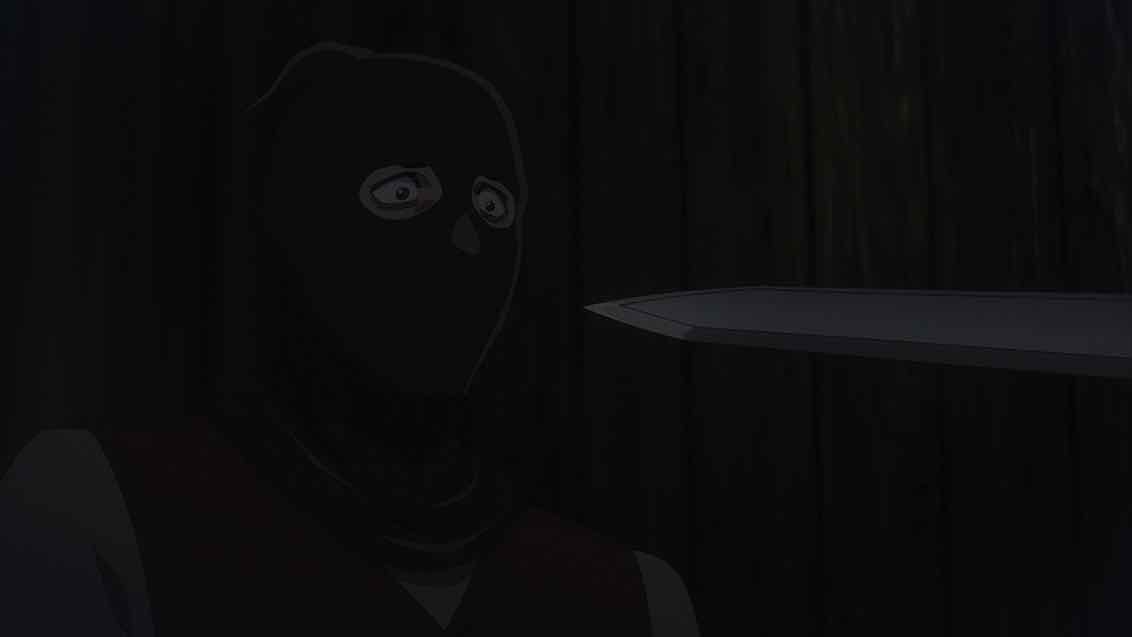

When Mars defies his perfect observations – not only stops moving night after night, but backtracks – Gras once more descends into despair. Why was he chosen to survive not just the plague, but his own attempt to end his life? For once the pair are assigned not to a duel, but to guard a heretic (Sanpei Yuuki) on the way to the execution ground. Gras removes his hood, reasoning that there’s no harm in a condemned man on the way to the stake seeing his face. The heretic has a lot to say in spite of repeated warnings to desist, and hones in immediately on the gravest insecurities of his guards.

The heretic’s words are a challenge to church doctrine far more fundamentally than heliocentrism could ever be. He states the case flat-out – the church preys on the need of humans to believe death is not the end, that there’s some meaning to the suffering of existence (and in those days, that was a lot). He knows these men really can’t kill him no matter how he provokes them – they’d be condemning themselves if they robbed the Inquisition of its “justice”. But he offers proof that there’s something greater, proof that true beauty exists on the Earth if only we’ll open our eyes to it. Truth in a stone chest, hidden on the mountain their cart (Nowak and a monk are riding in the one in front) is passing.

Call this what you will – fate, a passing of the torch – but in Gras the heretic has found someone desperate enough to grab onto any lifeline offered to him. There are many fundamental questions being posed here, not least the idea of whether asking questions is in itself incompatible with the concept of faith. Oczy is in his way every bit as desperate as Gras, though in a different point on his intellectual and spiritual journey. A journey that’s clearly about to take a monumental leap forward on this rainy night.

Snowball

October 20, 2024 at 6:19 pmSo… Rafal is really gone? I’m so disappointed. But the ideas and conflict in this series are so riveting that I found myself really engrossed in this episode even with a bunch of new characters.

Guardian Enzo

October 20, 2024 at 6:25 pmI thought they made that pretty clear!

I agree, it was a jolt to lose him but the ideas live on (which is very much the point).

Snowball

October 20, 2024 at 7:06 pmThey did! I was being optimistic, which was silly considering the time period of the series left no room for optimism.