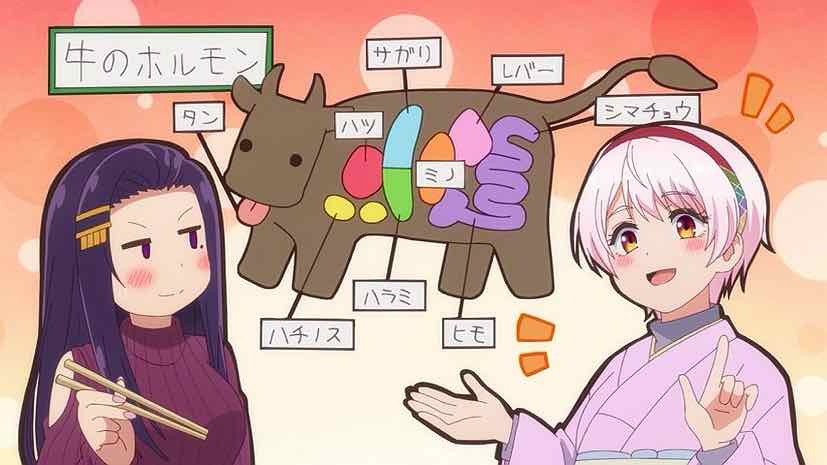

This is one of those shows that always makes me hungry.

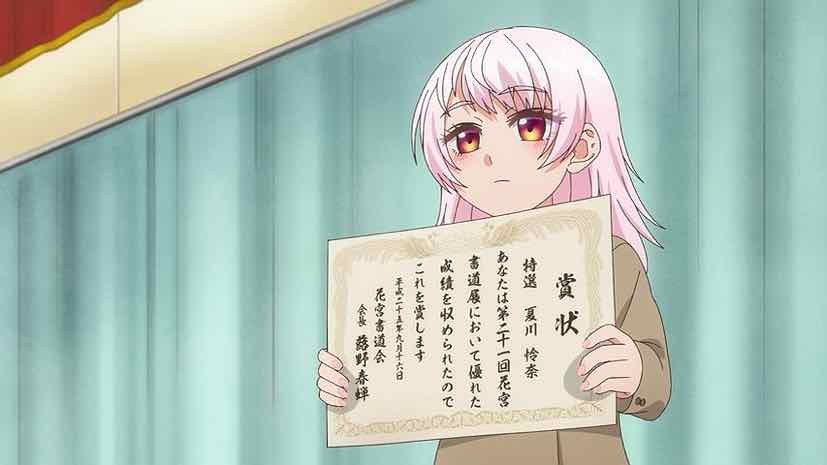

Dosanko Gal is another (in a long and august tradition) of anime on which I find my opinion diverging sharply from the general consensus. I really ought to stop reading the discussion about this series, because I just find it really inane for the most part. I touched on one aspect of it last week – the disbelief that any of these females could be interested in Tsubasa. It goes well beyond that, though. For whatever reason lots of people seem to find the very existence of Hokkaido Gals Are Super Adorable! as some kind of affront (so why are they still watching?). Though I suspect the reason is that it doesn’t conform to the tropes of the harem genre they’re so convinced it’s a part of.

It’s pretty obvious to me (and certainly not just me, judging by the comments here) that this show is not a mass-produced model where harem or even shounen romcoms are concerned. If that wasn’t already obvious Minami’s response to Wingmom’s emergency alert sealed the deal. I kind of wonder if Mai-san would have expected her daughter to react that way – I suspect not, though she rolled with it admirably.

I’ve been of the opinion from the start that Minami was really the only serious romantic possibility here, but I must confess that Tsubasa and Rena are more conventionally “couple-y” (the outfits accent that impression) while there’s still a “pals” air to he and Minami’s relationship. Minami’s instant reaction is to fangirl over Rena, and if she’s jealous of anybody one would guess it was Tsubasa. But then she does invite Sayuri along when she stakes out the date, which is probably a pretty telling move. Sayuri almost blows their cover angsting over Tsubasa’s crane game incompetence trying to win Rena a “Melon Kuma” (more Hokkaido realia, albeit terrifying), but she immediately has a much more conventionally unsettled reaction to this date.

It’s interesting listening in on the couple’s conversation. Rena is actually feeling somewhat unappreciated at home and clearly her whole nadeshiko persona is a cry for attention she isn’t getting. Tsubasa immediately grasps onto this, and reveals that he left Tokyo after a fight with his parents (I didn’t see that coming) over somewhat similar frustrations. There are indeed similarities between Rena and Tsubasa, and that further makes them seem like a natural couple. But it’s Minami’s situation that’s more or less the key to everything. While I have no doubt her admiration (hero worship) of Rena is genuine, her behavior here has a strong whiff of overcompensation to it.

More and more I think Minami’s life is one big lie. She plays the ever-cheerful and genki part so well she usually believes it herself, but there seems to be an emptiness there. Most obviously she’s simply trying too hard, pretty much all the time. She can sell the notion that she’s thrilled Rena and Tsubasa are going out, but I don’t buy it (and neither does Wingmom). The whole yakiniku invitation (this show is a weekly reminder that Hokkaido is the foodie capital of Japan) is Mai’s ploy to try and force Minami’s hand. And it works, in the sense that Minami whispers to Tsubasa after dinner that the next date is going to be with her.

It’s certainly an interesting dynamic brewing up here, though Sayuri seems hopelessly friendzoned already. Tsubasa is a bit of a chad in a tortoise-beats-the-hare kind of way – he seems to have an instinct for saying just the right thing to get into a girl’s head, and he’s a bit of a mystery with his odd Tokyo backstory. Rena is definitely starting to feel a tug, and Minami is going to have to be honest with her feelings (to herself, never mind to Tsubasa) if she wants to nip that in the bud. I’m still extremely confident that’s where Tsubasa’s heart goes in the end, but Rena certainly checks more conventional boxes.

ruicarlov

February 28, 2024 at 9:11 amQuite the season for rom-coms we’re getting. Never mind one, we’ve got two of those shows that handle things way differently from what we’re used to, and to a great effect, too. I was so ready for a angst/jealousy episode by Minami, but she dribbled my expected tropes perfectly, while demonstrating she wants in on the action, as well.

sonicsenryaku

February 28, 2024 at 11:09 amThe more I see of Hokkaido Gals, the more I become convinced that Minami is a soft subversion of the Gyaru archetype. As someone who has a decent understanding of the appeal of this growing sub genre I’ll dub, “Gyaru romantic comedies,” I’d argue that while Minami embodies quite a few of its superficial elements, she disrupts certain core expectations of the archetype as well. Typically, gyaru romantic comedies rely on the gap moe of subverting the unfavorable stereotype around gyarus: that being that they’re highly promiscuous, self-absorbed individuals who care too much about their appearance and possess a shallow perspective on life. These romantic comedies do this by going out of their way to make sure that the gyarus are portrayed as wholesome, kind-hearted, sexually innocent (while keeping the flirtatiousness for shenanigans, of course), and emotionally insightful individuals who are just experts at getting along with everyone and being cheerful all the time.

Last but certainly not least, the gap moe is accentuated even further by having them be attracted to a male who wouldn’t seem like their kind of guy according to the stereotype. This genre’s need to emphasize the gap moe oftentimes runs the risk of making the characters become amalgamations of static tropes that simply serve to perpetuate the serotonin-inducing formula as the audience tunes in each week to see what new interactions will highlight this feel-good gap moe some more, rather than the characters being dynamic takes on romantic archetypes and emerging from them as distinct individuals. Again, these romantic comedies at their core, simply serve to produce a weekly gap-moe effect through the gyaru character by subverting the unflattering stereotypes around them, which has now become the archetype of these female characters in these comedies.

Now enter Hokkaido Gals and how it handles the gyaru archetype, as rather than make Minami a one/two-dimensional gap-moe catalyst, her very gyaru nature is used as a character flaw to give us introspection into her behaviors and interactions with the cast. It’s almost as if the author was like, “what if Minami was genuinely a sweet, genki girl, but she also wasn’t as confident in herself as she makes it out to be and so uses her gyaru persona to compensate.” It’s not anything revolutionary narrative-wise; we’ve seen quite a few stories of characters who hide heavy emotional burdens behind their niceness and cheer, but what sells it here in its one unique realm is: 1. The way Minami is portrayed as deflecting her insecurities with her gyaru personality, 2. The choice to write Minami in this way having meaning, especially when looking at a genre that for the most part, is mostly derivative with the Gyaru archetype and doesn’t paint them with enough 3-dimensional identity that would distinguish any of them apart (at least of the handful i’ve read); and 3. the overall method with which writer derives consequences from the execution of this kind of character beat

Raikou

February 28, 2024 at 4:12 pmThe disbelief about the female characters could be interested in Tsubasa, I think it’s because the anime watchers (mostly males) don’t believe that nice/kindness only is enough to get pretty girls.

“if it was that easy, none of us would be single!”

I’m not generalizing all anime watchers, though. Discussion for this series is better at this blog, Enzo.

Guardian Enzo

February 28, 2024 at 7:52 pmDiscussion of most series is, ROFL. One of the reasons I keep the site going!

Richard

March 2, 2024 at 7:09 amIn the opening credits, Minani is the only girl next to Tsubasa. Flying, or standing, the others are always on her opposite side, or behind her. She is the FMC in my book then.