There’s a fundamental truth underlying much of what AI no Idenshi does, and it’s this: just because we can do something, doesn’t mean we necessarily should. That’s not a theme that’s limited to this premise of course, but artificial intelligence is a canvas especially well-suited to it. Once more here the series is not particularly interested in telling us what to think – merely asking us to think. It’s much more about the questions than the answers, and given the sort of questions it’s asking, that’s to its credit.

There’s a fundamental truth underlying much of what AI no Idenshi does, and it’s this: just because we can do something, doesn’t mean we necessarily should. That’s not a theme that’s limited to this premise of course, but artificial intelligence is a canvas especially well-suited to it. Once more here the series is not particularly interested in telling us what to think – merely asking us to think. It’s much more about the questions than the answers, and given the sort of questions it’s asking, that’s to its credit.

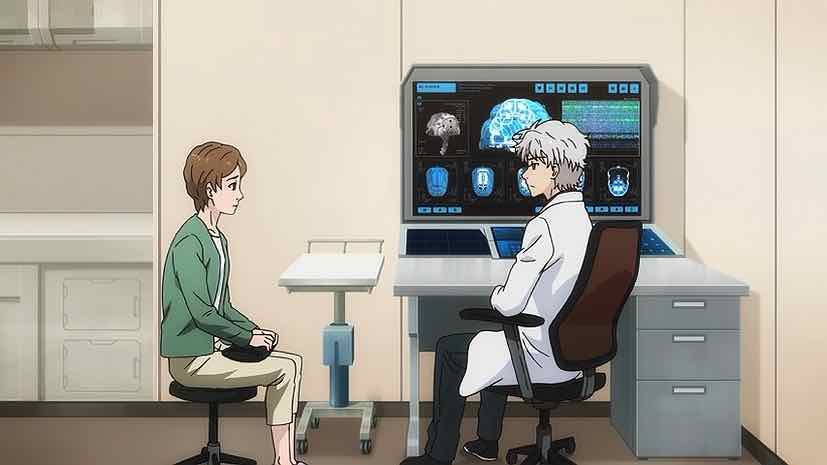

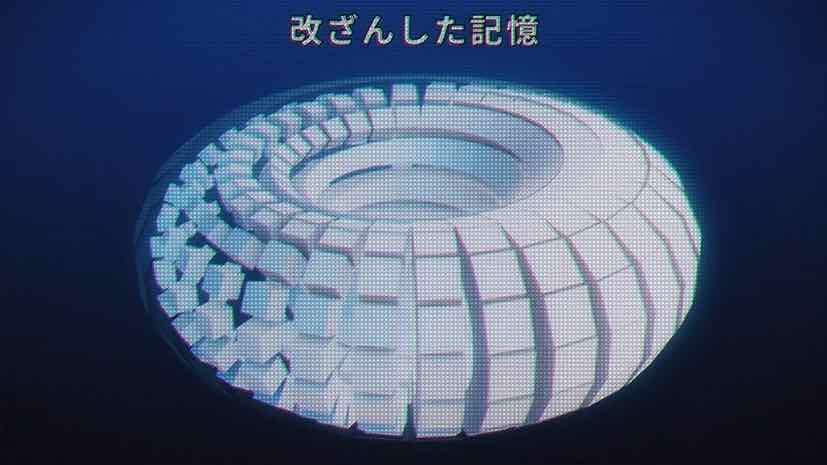

There are two thematically-linked stories here, both involving humanoids who’ve had their memories – and more – altered under very different circumstances. One is a married man named Matsumura, suffering from insomnia and nightmares. Upon examination Sudo finds that his memories were overwritten six years earlier, in an “invasive procedure:”. He immediately suspects who might have done the job, and seeks out an old associate named Seto (a humanoid himself) who runs a Moggadeet-like illicit clinic. It was indeed he who did the job, and he agrees to provide the data for Sudo to use in his treatment, but he clearly feels no remorse over the matter.

There are two thematically-linked stories here, both involving humanoids who’ve had their memories – and more – altered under very different circumstances. One is a married man named Matsumura, suffering from insomnia and nightmares. Upon examination Sudo finds that his memories were overwritten six years earlier, in an “invasive procedure:”. He immediately suspects who might have done the job, and seeks out an old associate named Seto (a humanoid himself) who runs a Moggadeet-like illicit clinic. It was indeed he who did the job, and he agrees to provide the data for Sudo to use in his treatment, but he clearly feels no remorse over the matter.

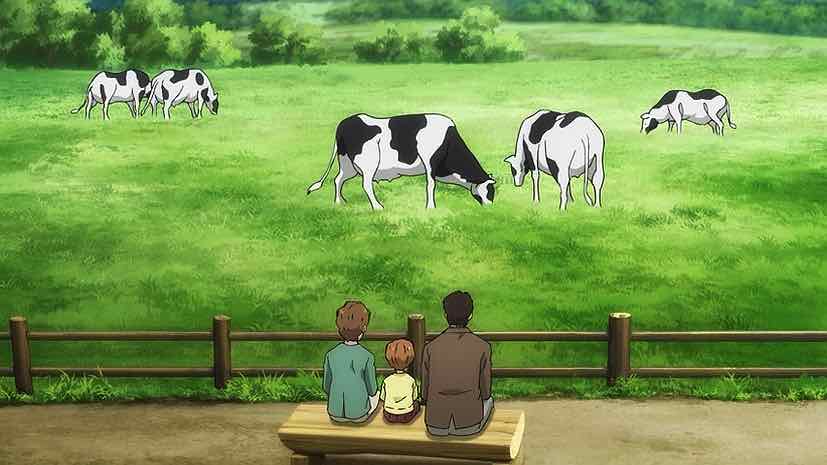

Matsumura was in bad shape when he came to Seto, no question about it. In effect, what he had done to him is something akin to a lobotomy or electroshock treatment, and it resulted in his losing his memories of his time before the treatment. He came to Seto to seek relief from his alcoholism, and perhaps Seto was not wrong in saying that Matsumura would just transfer his addictive personality to something else. Matsumura-san seems happy enough now, with a wife and child. But you can’t shake the sense that he’s perpetually aware than something isn’t quite right.

Matsumura was in bad shape when he came to Seto, no question about it. In effect, what he had done to him is something akin to a lobotomy or electroshock treatment, and it resulted in his losing his memories of his time before the treatment. He came to Seto to seek relief from his alcoholism, and perhaps Seto was not wrong in saying that Matsumura would just transfer his addictive personality to something else. Matsumura-san seems happy enough now, with a wife and child. But you can’t shake the sense that he’s perpetually aware than something isn’t quite right.

The second case, a humanoid boy named Yuta, is the more emotionally powerful and even more ethically grey. Yuta is like many children (usually boys) – prone to losing control of his emotions, impatient, self-absorbed. He’s also a certified genius as a pianist, which Sudo knows enough to appreciate. This case is so telling because it so closely mirrors what happens in the real world with drugs and children. It’s interesting that Sudo asks Jay to make a diagnosis for the mother, something we’ve never seen before. And Jay prescribes a “tuning” of Yuta’s emotions, to alter them a bit so that he’s in control and less angry.

The second case, a humanoid boy named Yuta, is the more emotionally powerful and even more ethically grey. Yuta is like many children (usually boys) – prone to losing control of his emotions, impatient, self-absorbed. He’s also a certified genius as a pianist, which Sudo knows enough to appreciate. This case is so telling because it so closely mirrors what happens in the real world with drugs and children. It’s interesting that Sudo asks Jay to make a diagnosis for the mother, something we’ve never seen before. And Jay prescribes a “tuning” of Yuta’s emotions, to alter them a bit so that he’s in control and less angry.

This is a tough one, to be sure. Yuta’s mom should have trusted her first instinct – “maybe that’s just how he is”. And when Risa asks Sudo if he thinks she’ll allow the treatment, he says yes – and then “It’s a shame”. But he still performs it, and Yuta is indeed changed. He doesn’t get into fights, he gets along with his classmates, he doesn’t get angry at his mother for interrupting his playing. But if it doesn’t rip your heart out when he says “I think my playing may sound different now, somehow”, I’m not sure you have a heart.

This is a tough one, to be sure. Yuta’s mom should have trusted her first instinct – “maybe that’s just how he is”. And when Risa asks Sudo if he thinks she’ll allow the treatment, he says yes – and then “It’s a shame”. But he still performs it, and Yuta is indeed changed. He doesn’t get into fights, he gets along with his classmates, he doesn’t get angry at his mother for interrupting his playing. But if it doesn’t rip your heart out when he says “I think my playing may sound different now, somehow”, I’m not sure you have a heart.

I don’t claim that it’s easy to say whether this was right or wrong, but I do have strong feelings about it. With humanoids, it’s much easier to “tune” a personality – with humans we have to do it with drugs. But if we’re to believe humanoids have all the rights of human beings, should be be altering them like this? Would we be OK with what was done to Yuta if we had the ability to do it to a human child? I suspect many – including many parents – would say yes. I’m not so sure. I think Yuta was altered for the benefit of others (including his mother), rather than himself. And maybe the line between fact and fiction here is not so clear-cut as we’d like to believe.

I don’t claim that it’s easy to say whether this was right or wrong, but I do have strong feelings about it. With humanoids, it’s much easier to “tune” a personality – with humans we have to do it with drugs. But if we’re to believe humanoids have all the rights of human beings, should be be altering them like this? Would we be OK with what was done to Yuta if we had the ability to do it to a human child? I suspect many – including many parents – would say yes. I’m not so sure. I think Yuta was altered for the benefit of others (including his mother), rather than himself. And maybe the line between fact and fiction here is not so clear-cut as we’d like to believe.

SeijiSensei

August 5, 2023 at 9:01 pmI kept thinking maybe Yuta should be in a music school. His obsessive genius might have been developed there without the outbursts of violence.

Guardian Enzo

August 5, 2023 at 10:24 pmOne possible solution. Adults trying to work with him rather than just shaming him might be another.