I want to talk – briefly – about Inu-Oh, Yuasa Masaaki’s very good (though not great) riff on the Heike legend and the birth of Noh. But I’m conscious that I can’t do so without referencing Saru’s other release on the theme, Heike Story (I can no longer bring myself even to refer to it by the Japanese title it shares with that infinitely superior work). And, frankly, I have no real desire to talk about that thing. It depresses me even to think about it, and no good can really come of my airing my grievances (which are myriad and intense) with it yet again.

So, what to do? It’s a conundrum, because Inu-Oh does deserve to be talked about. It has its flaws but it’s quite a powerful viewing experience and genuinely inventive. It also honors the spirit of Heike Monogatari far, far, more than that “adaptation” despite spinning a completely different story set two centuries or so later. What Yuasa has done here which that other thing did not is to make no pretense about adapting the original. And in doing so, liberate himself to tell a tale that can fit in the space it has to work with. And to give itself over to original material because, despite being loosely based on historical figures and events, this is completely original – untethered from the details of any source material or earlier version.

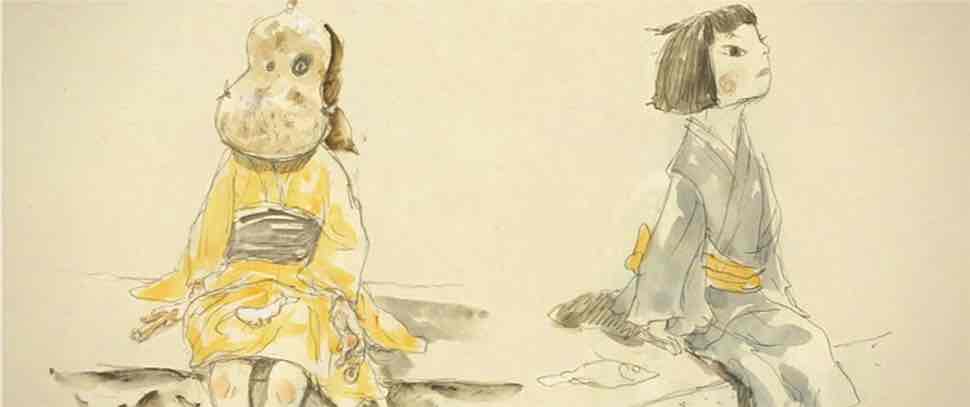

In brief, Yuasa’a story is about a young Biwa monk named Tomona (Moriyama Mirai) – as far as I know a completely fictional character – and Inu-Oh (Ayu-chan), loosely based on a famous sarugaku performer of the period. Sarugaku was one of the two predecessors of Noh – the other being dengaku. Sarugaku was the more lively and plebeian, incorporating acrobatics and taiko in a manner akin to a modern circus. Both forms influenced each other and were formative in modern Noh, though stylistically sarugaku proved to be the more resilient and eventually dominant.

The Heike connection comes through the Tomona character, who lived in the village closest to where the battle of Dan-no-Ura was waged – a village that trades on finding Heike treasures sunk to the bottom of the Shimonoseki Strait. One day men belonging to the Shogun, Yoshimitsu, come to the village offering a sizable reward if the lost Imperial Regalia of Emperor Antoku (the sword) can be recovered. Young Tomona and his father find it, but it turns out to be cursed – the father dies and Tomona is blinded. The spirit of his dead father demands he be avenged, and eventually Tomona comes under the care of the Biwa Hoshi and learns their trade.

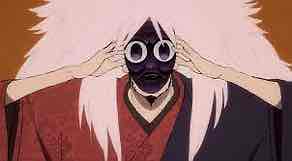

As for Inu-Oh, he’s the cruelly deformed eldest son of the sarugaku Hie-za troupe’s master, and there are strong elements of Dororo in his story. His father sold his life to a demon in order to achieve greater fame, and every time Inu-oh performs one of the “new” Heike tales and liberates the restless spirit of a Heike warrior, he gets part of his original body back. He and Tomona – now Tomoichi of the Biwa Hoshi – meet as boys and grow to manhood together, perfecting a new style of performance that, charitably, no one in the 14th Century ever laid eyes on. In the process Inu-Oh becomes massively popular and so do his tales – which the Shogun is quite threatened by.

Turning this story effectively into a rock opera was a bold choice by Yuasa, to be sure. His casting decisions reflect that choice – Ayu-chan is a rock star of course, and Moriyama a star of musical theater (Western theater that is). And the music, while obviously about as anachronistic as theoretically possible, is infectious and effective. These two are insurgents, especially Tomoichi (now Tomoari), and eventually are faced with the usual insurgent’s choice – conform or pay the price. They choose differently, with different results, and it’s worth noting that while Inuou was not remembered as widely as rival Fujiwaka (a minor character here, who the Shogun initiated an affair with when he was 12, and who was in fact a great admirer of Inuou) he nevertheless is recorded as one of the greatest Noh performers of any time.

I think, when faced with a work as monumentally sublime and powerful as Heike Monogatari, a creator has two good options. They can attempt a materially faithful adaptation, or they can spin off something totally original based on the influence of the source work. Science SARU never did the former, but through Yuasa’s film they’ve made a very strong pass at the latter. The message of the film is reflected in the reality of its existence – the freedom to tell new stories enlivens the original, it doesn’t diminish it. It’s a film that recognizes the tragedy of the Taira and honors their memory far more faithfully than Saru’s other 2021 work does. And ironically, despite not being an adaptation at all, stands as anime’s most authentic take on one of the most moving stories ever told.

Joshua

December 25, 2022 at 2:15 amThe thing about that 2021 “adaptation” of Heike Monogatari was that it wasn’t really an adaptation of the original text (that was translated into English by Royall Tyler in its most recent international version). It was actually an adaptation of the 2016 version of the text that was translated into modern Japanese by Hideo Furukawa, who also wrote the novel that inspired Inu-Oh the following year. I just want to make that clear, because I think that was why you thought the series “betrayed” the source material because you were expecting it to adhere to an older translation, when really it was adhering to a different take on the text.

Anyways, getting back on topic, good review on my favorite anime film of this year.

Guardian Enzo

December 25, 2022 at 9:00 amI’m aware of all that and I don’t think it make a drop of difference. Just MHO.