I’ve talked a lot about Dennou Coil on this site for a show I didn’t blog (because it aired three years before LiA existed). And with good reason – it’s a wonderful series, from an even more wonderful year. But absent rose-colored nostalgia obscuring their vision, one sees significant flaws. In many ways Dennou Coil feels like a show with a lot of unrealized potential. Iso Mitsuo being who he is, of course it’s bursting with fascinating ideas. But the second cour has a meandering quality to it, and a lot of the threads unspooled in the first half are never tied up (or outright ignored) in the second. Whether that’s the result of the tumult behind the scenes of the production I don’t know, but for me it’s an inescapable fact.

I’ve talked a lot about Dennou Coil on this site for a show I didn’t blog (because it aired three years before LiA existed). And with good reason – it’s a wonderful series, from an even more wonderful year. But absent rose-colored nostalgia obscuring their vision, one sees significant flaws. In many ways Dennou Coil feels like a show with a lot of unrealized potential. Iso Mitsuo being who he is, of course it’s bursting with fascinating ideas. But the second cour has a meandering quality to it, and a lot of the threads unspooled in the first half are never tied up (or outright ignored) in the second. Whether that’s the result of the tumult behind the scenes of the production I don’t know, but for me it’s an inescapable fact.

Fast-forward (well, hardly – 15 years) to Chikyuugai Shounen Shoujo, and things seem very different. I would love to have seen what Iso-sensei could have done with this premise given the 26 episodes he got with Dennou Coil. Or even 12 or 13, rather than the six (about eight in TV terms) he got. But the runtime of The Orbital Children is not entirely, it seems to me, a negative. Iso clearly scripted this story to fit the time he had, and it shows. Is there something in Iso that makes a shorter runtime – with the discipline it imparts – an advantage (as may be the case with Ikuhara Kunihiko, for example)? Or is this simply a more disciplined piece of writing, 15 years later?

Fast-forward (well, hardly – 15 years) to Chikyuugai Shounen Shoujo, and things seem very different. I would love to have seen what Iso-sensei could have done with this premise given the 26 episodes he got with Dennou Coil. Or even 12 or 13, rather than the six (about eight in TV terms) he got. But the runtime of The Orbital Children is not entirely, it seems to me, a negative. Iso clearly scripted this story to fit the time he had, and it shows. Is there something in Iso that makes a shorter runtime – with the discipline it imparts – an advantage (as may be the case with Ikuhara Kunihiko, for example)? Or is this simply a more disciplined piece of writing, 15 years later?

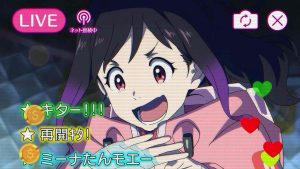

The remarkable thing is that Chikyuugai Shounen Shoujo is no less thematically ambitious than Dennou Coil. Being so much shorter, it loses something in terms of texture but gains something in terms of clarity. What unites the two works is Iso’s unerring deftness at portraying children – a bit older here in the main, but children nonetheless. This is a story about nothing less than the future of humanity, so it seems only fitting that children should be its unerring focus.

The remarkable thing is that Chikyuugai Shounen Shoujo is no less thematically ambitious than Dennou Coil. Being so much shorter, it loses something in terms of texture but gains something in terms of clarity. What unites the two works is Iso’s unerring deftness at portraying children – a bit older here in the main, but children nonetheless. This is a story about nothing less than the future of humanity, so it seems only fitting that children should be its unerring focus.

Essentially, we have a story of an anti-science global bureaucracy facing off against a doomsday terrorist group that manages to be optimistic, which is remarkable in itself. The hope, of course, lies in individuals – especially children. Which obviously may be idealistic, but that’s the privilege of fiction (historically, especially science-fiction). That Nasa is a terrorist there can be no doubt. Couching it in terms of saving humanity doesn’t mitigate the fact that she’s trying to engineer the murder of literally billions of people. Neither does her intention not to kill anyone on-board the station. Her prophecy may mostly be true, but her reading of it is irreparably and indefensibly warped.

Essentially, we have a story of an anti-science global bureaucracy facing off against a doomsday terrorist group that manages to be optimistic, which is remarkable in itself. The hope, of course, lies in individuals – especially children. Which obviously may be idealistic, but that’s the privilege of fiction (historically, especially science-fiction). That Nasa is a terrorist there can be no doubt. Couching it in terms of saving humanity doesn’t mitigate the fact that she’s trying to engineer the murder of literally billions of people. Neither does her intention not to kill anyone on-board the station. Her prophecy may mostly be true, but her reading of it is irreparably and indefensibly warped.

Touya-kun is, of course, the one at the crux of all these ethical questions. As Nasa gleefully throws in his face, he espoused many of the same ideas she – in John Doe’s name – is trying to bring to fruition. But one of the many big ideas Iso chews on in The Orbital Children is the notion of “humans” vs. “humanity”. The lack of recognition of the individual is the heart of fascism, and and has been intrinsic to uncountable atrocities throughout human history. It’s all about frame (a big word here) of reference. Touya’s expanded – and with the nearly-magical powers of adaptability a 14 year-old possesses, he changed.

Touya-kun is, of course, the one at the crux of all these ethical questions. As Nasa gleefully throws in his face, he espoused many of the same ideas she – in John Doe’s name – is trying to bring to fruition. But one of the many big ideas Iso chews on in The Orbital Children is the notion of “humans” vs. “humanity”. The lack of recognition of the individual is the heart of fascism, and and has been intrinsic to uncountable atrocities throughout human history. It’s all about frame (a big word here) of reference. Touya’s expanded – and with the nearly-magical powers of adaptability a 14 year-old possesses, he changed.

This notion of “frame” is a big key to Chikyuugai. It’s a supremely important part of Japanese culture honestly, to the point where the entire language is molded around the concept. These circles, groups, whatever you call them are the defining reality of Japanese life. My family, not my family. My company, not my company. My senior, my junior, my level. Where you fit – and where you don’t – controls the way Japanese people are expected to interact with you, right down to the form of the language they use to talk to you.

This notion of “frame” is a big key to Chikyuugai. It’s a supremely important part of Japanese culture honestly, to the point where the entire language is molded around the concept. These circles, groups, whatever you call them are the defining reality of Japanese life. My family, not my family. My company, not my company. My senior, my junior, my level. Where you fit – and where you don’t – controls the way Japanese people are expected to interact with you, right down to the form of the language they use to talk to you.

As Second Seven evolves into Infinite Seven and increasingly dominates the plot, frame asserts its importance. Konoha and Touya are inside its frame, because it created the implants that extended their lives (and now may end them). There was even a moment, on the lunar surface, with the original Seven (Lunatic) tried to communicate with them. That will become critical when they try and communicate with “new” Seven after Nasa has destroyed the ICS antenna (and then herself) in a bid to stop them from interfering. But the only way to communicate with it is to let it see all of humanity, warts and all – the internet.

As Second Seven evolves into Infinite Seven and increasingly dominates the plot, frame asserts its importance. Konoha and Touya are inside its frame, because it created the implants that extended their lives (and now may end them). There was even a moment, on the lunar surface, with the original Seven (Lunatic) tried to communicate with them. That will become critical when they try and communicate with “new” Seven after Nasa has destroyed the ICS antenna (and then herself) in a bid to stop them from interfering. But the only way to communicate with it is to let it see all of humanity, warts and all – the internet.

This is a purely sci-fi moment for Iso, his unabashed argument for free thought and the advancement of learning. Indeed this new Seven has been in a “cradle”, as it’s only seen what John Doe allowed it to see. Konoha is surely speaking for Iso when she asks whether exposing a child only to its parents’ biases will produce a good person. A good parent, rather, will let the child see the world as it really is, and trust that the lessons they’ve tried to teach it will steer it through the minefield of knowledge. It’s not an easy path to be sure, but the easy path is often not the best one to follow.

This is a purely sci-fi moment for Iso, his unabashed argument for free thought and the advancement of learning. Indeed this new Seven has been in a “cradle”, as it’s only seen what John Doe allowed it to see. Konoha is surely speaking for Iso when she asks whether exposing a child only to its parents’ biases will produce a good person. A good parent, rather, will let the child see the world as it really is, and trust that the lessons they’ve tried to teach it will steer it through the minefield of knowledge. It’s not an easy path to be sure, but the easy path is often not the best one to follow.

In purely human terms, it would certainly suck if Seven engineered it for Konoha to die here, with her role completed. But it fits with the notion that Seven holds separate definitions for humans and humanity – with the welfare of the latter being its prime directive. That Seven was kept in a cradle too, and perhaps this new one, knowing what it knows now, wouldn’t have made that choice. For Touya, Konoha has always been one of the few humans that mattered, and he and she are linked both literally and spiritually in a deeper way than anyone in the cast. If Infinite Seven can learn anything from observing humanity, surely seeing that would provide one of its most essential lessons.

In purely human terms, it would certainly suck if Seven engineered it for Konoha to die here, with her role completed. But it fits with the notion that Seven holds separate definitions for humans and humanity – with the welfare of the latter being its prime directive. That Seven was kept in a cradle too, and perhaps this new one, knowing what it knows now, wouldn’t have made that choice. For Touya, Konoha has always been one of the few humans that mattered, and he and she are linked both literally and spiritually in a deeper way than anyone in the cast. If Infinite Seven can learn anything from observing humanity, surely seeing that would provide one of its most essential lessons.