As a general rule, I tend to try and write about an anime episode as soon as possible after it’s concluded. I like the have things fresh in my mind and let my impressions more or less dictate the direction of my review (I’m not a big outliner, even when it comes to fiction). Somehow though, that just doesn’t work with Beastars. This is a series where I have to at least try and organize my thoughts before I can analyze it. So this time I cranked up some Tenacious D on Youtube and vegged out for a bit, hoping the break would lend me some clarity of purpose.

As a general rule, I tend to try and write about an anime episode as soon as possible after it’s concluded. I like the have things fresh in my mind and let my impressions more or less dictate the direction of my review (I’m not a big outliner, even when it comes to fiction). Somehow though, that just doesn’t work with Beastars. This is a series where I have to at least try and organize my thoughts before I can analyze it. So this time I cranked up some Tenacious D on Youtube and vegged out for a bit, hoping the break would lend me some clarity of purpose.

It didn’t work, but the thing is that I kind of enjoy the aspect of not really being able to categorize what I’m seeing because it’s so rare in anime these days. Trying to get inside the author’s head is often a bad idea, but I don’t see any way to watch Beastars without doing so. I have no idea whether this works as a story if taken literally, because I have absolutely no ability to try. I see symbolism and metaphor everywhere I look, and I’m not usually sure whether it’s coming from Itagaki or coming from me.

It didn’t work, but the thing is that I kind of enjoy the aspect of not really being able to categorize what I’m seeing because it’s so rare in anime these days. Trying to get inside the author’s head is often a bad idea, but I don’t see any way to watch Beastars without doing so. I have no idea whether this works as a story if taken literally, because I have absolutely no ability to try. I see symbolism and metaphor everywhere I look, and I’m not usually sure whether it’s coming from Itagaki or coming from me.

One thing is clear. In this mythology, carnivores being carnivores is a crime. Yet in spite of that, they have all the natural impulses any carnivore would have. This obviously sets them up for a strange and often highly confused existence, and no matter how much Cherryton tries to act as a bubble (which it very clearly does) the outside world still seeps in. When an herbivore is killed in a “predation incident” in town (this news was read by a carnivore newscaster), it ripples onto campus. Herbivore students are forbidden from going into town, and the wrong sort of carnivores are subject to bullying on campus.

One thing is clear. In this mythology, carnivores being carnivores is a crime. Yet in spite of that, they have all the natural impulses any carnivore would have. This obviously sets them up for a strange and often highly confused existence, and no matter how much Cherryton tries to act as a bubble (which it very clearly does) the outside world still seeps in. When an herbivore is killed in a “predation incident” in town (this news was read by a carnivore newscaster), it ripples onto campus. Herbivore students are forbidden from going into town, and the wrong sort of carnivores are subject to bullying on campus.

It’s in this environment that Legosi steps in to help a canine girl being bullied – awkwardly, because he does everything awkwardly, but unhesitatingly. This girl is Juno (the very talented Tanizaki Atsumi), like Legosi a grey wolf, though their lack of resemblance makes his cover story of being her big brother a stretch. She turns out to be a first year member of the drama club and seemingly a very nice girl, and thus by any measure a far more logical potential partner for Legosi than Haru. But there aren’t really the same sparks here, which as much as anything suggests Legosi’s heart is already committed.

It’s in this environment that Legosi steps in to help a canine girl being bullied – awkwardly, because he does everything awkwardly, but unhesitatingly. This girl is Juno (the very talented Tanizaki Atsumi), like Legosi a grey wolf, though their lack of resemblance makes his cover story of being her big brother a stretch. She turns out to be a first year member of the drama club and seemingly a very nice girl, and thus by any measure a far more logical potential partner for Legosi than Haru. But there aren’t really the same sparks here, which as much as anything suggests Legosi’s heart is already committed.

When a quartet of carnivore boys head off on an errand to do prep work for the festival performance, we get our first real look at the outside world. And it’s one where carnivores and herbivores seem to co-exist peacefully But there’s a hidden underworld here, the black market – which Louis has warned the boys to avoid. And when they stumble upon an old – wildebeest, maybe? – things get really weird. He offers to sell Legosi a finger to consume, which naturally horrifies Legosi. But Bill is of course all in favor, and even Legosi’s eagle friend Aoba (Kanemasa Ikuto) seems to feel as if school rules shouldn’t apply here.

When a quartet of carnivore boys head off on an errand to do prep work for the festival performance, we get our first real look at the outside world. And it’s one where carnivores and herbivores seem to co-exist peacefully But there’s a hidden underworld here, the black market – which Louis has warned the boys to avoid. And when they stumble upon an old – wildebeest, maybe? – things get really weird. He offers to sell Legosi a finger to consume, which naturally horrifies Legosi. But Bill is of course all in favor, and even Legosi’s eagle friend Aoba (Kanemasa Ikuto) seems to feel as if school rules shouldn’t apply here.

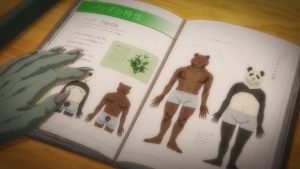

Long and short of it, this is the gateway to the black market – and eventually Legosi, drooling uncontrollably, passes out and winds up locked up in the office of the black market’s doctor/security man, a panda named Gouhin (unmistakably Ohtsuka Akio). Honor student Legosi knows enough about pandas to know the unique niche they fill – a bear who survives on nothing but bamboo, a sort of bridge between the two worlds. He strongly implies that Legosi has hunted and killed before, and eventually turns therapist – warning him that his interest in Haru is actually his hunting instinct masquerading as his heart. He eventually sends the young wolf on his way with a bunny porn mag to test his theory, but I suspect (and hope) we haven’t see the last of him.

Long and short of it, this is the gateway to the black market – and eventually Legosi, drooling uncontrollably, passes out and winds up locked up in the office of the black market’s doctor/security man, a panda named Gouhin (unmistakably Ohtsuka Akio). Honor student Legosi knows enough about pandas to know the unique niche they fill – a bear who survives on nothing but bamboo, a sort of bridge between the two worlds. He strongly implies that Legosi has hunted and killed before, and eventually turns therapist – warning him that his interest in Haru is actually his hunting instinct masquerading as his heart. He eventually sends the young wolf on his way with a bunny porn mag to test his theory, but I suspect (and hope) we haven’t see the last of him.

For all its thematic complexity and the endless interpretations it invites, Beastars for me tends to boil down to this – what does it mean to be a carnivore in this mythology? Certainly Legosi and Aoba come off as admirable for their determination not to go over to the dark side. But can it really be acceptable for a large group of people (in this context, that’s what they are) to live their entire lives in constant warfare with their true natures? We’ve seen the underlying truth to this seemingly idyllic world – meat-eaters getting their jones feasting on hospital and morgue castoffs, herbivores selling themselves piece by piece (literally).

For all its thematic complexity and the endless interpretations it invites, Beastars for me tends to boil down to this – what does it mean to be a carnivore in this mythology? Certainly Legosi and Aoba come off as admirable for their determination not to go over to the dark side. But can it really be acceptable for a large group of people (in this context, that’s what they are) to live their entire lives in constant warfare with their true natures? We’ve seen the underlying truth to this seemingly idyllic world – meat-eaters getting their jones feasting on hospital and morgue castoffs, herbivores selling themselves piece by piece (literally).

As always, it comes down to trying to guess Itagaki’s motives – just how metaphorical are we being here? Legosi’s attitude towards adulthood – associating it with the meat taboo – strongly suggests that carnivorousness is really just sex, and being symbolically framed in much the same way it was in FLCL. But when the protagonist’s romantic desire runs headlong into the practical contradiction inherent in the premise, that takes things to a whole new level. Or maybe Itagaki is just saying that men are inherently beasts and predators by their nature, and only through lifelong commitment can they suppress it – who knows.

As always, it comes down to trying to guess Itagaki’s motives – just how metaphorical are we being here? Legosi’s attitude towards adulthood – associating it with the meat taboo – strongly suggests that carnivorousness is really just sex, and being symbolically framed in much the same way it was in FLCL. But when the protagonist’s romantic desire runs headlong into the practical contradiction inherent in the premise, that takes things to a whole new level. Or maybe Itagaki is just saying that men are inherently beasts and predators by their nature, and only through lifelong commitment can they suppress it – who knows.

Gracie

November 15, 2019 at 5:12 amBinge read the manga two weeks ago and that scene at the black market, really took me by surprise.

ASade

November 15, 2019 at 11:05 amYeah, some manga readers call that scene a turning point in the manga, because it gets so much darker and more disturbing, cranking the intensity up to eleven. On the other hand, Enzo’s coverage has already explored the psychological aspects so deeply, such that this seems like a natural transition.

What did you think of that scene with the old man, Enzo? Did it take you by surprise at all?

Guardian Enzo

November 15, 2019 at 11:34 amLet’s just say my reaction matched the description I gave to Legosi’s.

Snoeplau

November 15, 2019 at 1:28 pmI don’t believe the author wants you to get inside his head. To me he’s inviting you to look into myriad personalities and pick those that resonate with you. You then identify with the characters in question and share their emotions. That’s how I got drawn into the story, ending up feeling Legosi’s frustration. That’s what makes this anime so unique!

Guardian Enzo

November 15, 2019 at 3:43 pmShe, for the record.

I think that aspect of it works too, but I’ve read too much fiction not to see some heavy symbolism at work here too.

Yann

November 17, 2019 at 11:26 amI definitely don’t think the metaphor is about sex. The fact that we simultaneously have sex addressed quite literally seems to corroborate that. My take on it is that it’s about the most obvious parallels we can think of: race and class. But the way the parallels are drawn is less than obvious, on purpose. I think of it as some sort of “emotional impressionism” where the carnivore thing is used quite literally and is only meant as a tool to evoke feelings that can be found in humans, not as a way to draw direct parallels on a societal/system level.

Nadavu

November 20, 2019 at 3:37 amOh God, what a blast to the face that was. The hobo wildebeest, the (what seemed like at first) torture chamber with a vigilante carnivore disposer, the rabbit porn mag… Things just scaled up to ten and then kept on raising.

I’d like to agree with Yann. I no longer feel like the herbivore/carnivore thing is a metaphor for sex and gender wars. We’re also seeing more and more male herbivores and female carnivores. Maybe there isn’t a metaphor here at all; perhaps it’s just a story that isn’t supposed to mean anything beyond being entertaining. Not that I believe it, by at this point, I’m not willing to presuppose anything.

By the way, I always thought panda bears are only bears by name and are actually a type of oversized raccoons, but I looked it up and apparentally the accepted wisdom has changed in the early 2000’s on how to clasify our bamboo-crzaed friends.