I won’t lie – that was an episode that really had me grinding for a long time on just what to make of it. Brilliant to be sure, unsparing and dark and brutal without a doubt. But with Yukimura Makoto it’s absolutely clear that there are no accidents. Everything about the man is meticulous – his preparation, his research, his scene-setting, his exposition. If he shows us something like what we saw this week, it’s because he wants to make a point. But that doesn’t mean it’s going to be immediately clear just what that is.

I won’t lie – that was an episode that really had me grinding for a long time on just what to make of it. Brilliant to be sure, unsparing and dark and brutal without a doubt. But with Yukimura Makoto it’s absolutely clear that there are no accidents. Everything about the man is meticulous – his preparation, his research, his scene-setting, his exposition. If he shows us something like what we saw this week, it’s because he wants to make a point. But that doesn’t mean it’s going to be immediately clear just what that is.

I’m going to generalize a bit here, but when a Japanese author writes about Christianity, I think it’s best to try and avoid reading it through the usual Western lens. Whatever our personal choice of religion (or lack thereof) is, those of us that grow up in America or Western Europe are presented the world from a Christian perspective. Perhaps a Japanese writer has an ability to be more objective than a Western writer would. Perhaps there are nuances that writer might not perceive that a Western writer would. Either way, the perspective of the writer is different in important ways.

I’m going to generalize a bit here, but when a Japanese author writes about Christianity, I think it’s best to try and avoid reading it through the usual Western lens. Whatever our personal choice of religion (or lack thereof) is, those of us that grow up in America or Western Europe are presented the world from a Christian perspective. Perhaps a Japanese writer has an ability to be more objective than a Western writer would. Perhaps there are nuances that writer might not perceive that a Western writer would. Either way, the perspective of the writer is different in important ways.

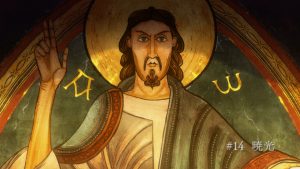

To complicate matters still further, what Yukimura is doing in Vinland Saga is not setting off Christianity in contrast with Shinto or Buddhist thought (which we see in manga and anime here and there). Rather, he’s contrasting Christian and pre-Christian Europe – and what a fascinating story emerges. The truth of the matter is for most people living in most places in the world in the 11th Century, life pretty much sucked. There was rarely enough food unless you were an aristocrat, disease was rampant, war religious and otherwise endemic. One could hardly blame anyone, wherever they were, from taking to take some solace from wherever they could find it.

To complicate matters still further, what Yukimura is doing in Vinland Saga is not setting off Christianity in contrast with Shinto or Buddhist thought (which we see in manga and anime here and there). Rather, he’s contrasting Christian and pre-Christian Europe – and what a fascinating story emerges. The truth of the matter is for most people living in most places in the world in the 11th Century, life pretty much sucked. There was rarely enough food unless you were an aristocrat, disease was rampant, war religious and otherwise endemic. One could hardly blame anyone, wherever they were, from taking to take some solace from wherever they could find it.

Is Yukimura-sensei judging his subjects here? And if so, which side is he judging more harshly? The Christians of Britain are certainly presented as a naive lot at times. Yet they scrabble together an existence as best they can, and give meaning to their misery with the promise of something better after death. The Danes, by contrast, seem to live for the moment. They take what they’re strong enough to take from those too weak to resist, and pre-emptively kill in order to protect their interests even if the “enemy” is women and children. Is it their contrasting view of paradise that drives this narrative? For Christians the path to salvation is piety and devotion. For the old Norse it’s glory in battle, plain and simple. Is this really all just about getting into Heaven or Valhalla?

Is Yukimura-sensei judging his subjects here? And if so, which side is he judging more harshly? The Christians of Britain are certainly presented as a naive lot at times. Yet they scrabble together an existence as best they can, and give meaning to their misery with the promise of something better after death. The Danes, by contrast, seem to live for the moment. They take what they’re strong enough to take from those too weak to resist, and pre-emptively kill in order to protect their interests even if the “enemy” is women and children. Is it their contrasting view of paradise that drives this narrative? For Christians the path to salvation is piety and devotion. For the old Norse it’s glory in battle, plain and simple. Is this really all just about getting into Heaven or Valhalla?

I think it goes deeper than that, to be sure. But at the center of it, always, is Askeladd. We tend to romanticize men like him in fiction – I do it myself by calling him a magnificent bastard. But he’s a brutal man, possessed of no mercy or kindness for its own sake. Lives are a calculus, not a moral or ethical concern. The villagers he murders aren’t people at all to him, seemingly, but resources and hinderances. This is purely my projection, but I don’t think Askeladd is concerned either with getting into Heaven (obviously) or Valhalla. My sense of the man is that he’s someone who understands that his go-around is the only one he gets, and he knows what’s waiting for him at the end of it. He’s going to do what he wants on this Earth because when his life ends, it’s over for good – there’s no reason to hold back.

I think it goes deeper than that, to be sure. But at the center of it, always, is Askeladd. We tend to romanticize men like him in fiction – I do it myself by calling him a magnificent bastard. But he’s a brutal man, possessed of no mercy or kindness for its own sake. Lives are a calculus, not a moral or ethical concern. The villagers he murders aren’t people at all to him, seemingly, but resources and hinderances. This is purely my projection, but I don’t think Askeladd is concerned either with getting into Heaven (obviously) or Valhalla. My sense of the man is that he’s someone who understands that his go-around is the only one he gets, and he knows what’s waiting for him at the end of it. He’s going to do what he wants on this Earth because when his life ends, it’s over for good – there’s no reason to hold back.

Bookending this episode are the drunken priest and the young girl Anne (Hara Yumi), the only villager to survive the massacre. Askeladd’s men continue to sport with the priest in seemingly good-natured fashion, but their conversations are getting deeper and deeper. For the first time Priest-san’s attention is really snared with the mention of Thors (though not by name). In the tale of the man who defeated 30 enemies without slaying a one, who claimed before his death that a true warrior was one who didn’t need a sword, Priest-san finally hears a description of the kind of love he continually fails to describe to Askeladd’s men. That priest will later try and warn the villagers before they’re captured – the first real act of courage we’ve seen from him, and one which earns him a beating and a warning from Askeladd that Canute’s friend or no, it will be the only warning he gets.

Bookending this episode are the drunken priest and the young girl Anne (Hara Yumi), the only villager to survive the massacre. Askeladd’s men continue to sport with the priest in seemingly good-natured fashion, but their conversations are getting deeper and deeper. For the first time Priest-san’s attention is really snared with the mention of Thors (though not by name). In the tale of the man who defeated 30 enemies without slaying a one, who claimed before his death that a true warrior was one who didn’t need a sword, Priest-san finally hears a description of the kind of love he continually fails to describe to Askeladd’s men. That priest will later try and warn the villagers before they’re captured – the first real act of courage we’ve seen from him, and one which earns him a beating and a warning from Askeladd that Canute’s friend or no, it will be the only warning he gets.

As for Anne, she seems to represent Yukimura’s cynicism towards Christianity. She tries hard to be good, and seems to believe the stories her priest father tells her of the coming armageddon. But the only team she feels alive is when she’s wicked – such as the moment she steals a ring from the traveling market. She still thrills every time she wears it, even as she’s racked with guilt over doing so. And when she – after having slipped away at the right moment to covertly wear her ring – manages to avoid the massacre of her family and village, she tells God that it makes her feel a sense of elation. Maybe Yukimura is telling us that human nature has an innate need to feel the thrill of existence no matter how we try and suppress it – or maybe I’m projecting again.

As for Anne, she seems to represent Yukimura’s cynicism towards Christianity. She tries hard to be good, and seems to believe the stories her priest father tells her of the coming armageddon. But the only team she feels alive is when she’s wicked – such as the moment she steals a ring from the traveling market. She still thrills every time she wears it, even as she’s racked with guilt over doing so. And when she – after having slipped away at the right moment to covertly wear her ring – manages to avoid the massacre of her family and village, she tells God that it makes her feel a sense of elation. Maybe Yukimura is telling us that human nature has an innate need to feel the thrill of existence no matter how we try and suppress it – or maybe I’m projecting again.

It’s not as though Yukimura has to have a larger point to make in all that happens in this episode – he doesn’t owe us that. It’s just that I know he’s trying to make one. There’s a clear and fundamental conflict in all this for Canute and Ragnar, as Christians to be accomplices in the slaughter of fellow Christians (that they’re innocents should be enough, but in practice we know that detail matters). Every day Thorfinn is not just complicit but an active participant in this life is a betrayal of the life his father laid down for his. Only Askeladd seems to be free of such conflicts, living for its own sake – but he’s living a lie just the same, using men he says he hates to slaughter indiscriminately. Even for a man like Askeladd, I suspect life has meaning – and that be believes there are existential consequences for the choices he makes, even if limited to this world.

It’s not as though Yukimura has to have a larger point to make in all that happens in this episode – he doesn’t owe us that. It’s just that I know he’s trying to make one. There’s a clear and fundamental conflict in all this for Canute and Ragnar, as Christians to be accomplices in the slaughter of fellow Christians (that they’re innocents should be enough, but in practice we know that detail matters). Every day Thorfinn is not just complicit but an active participant in this life is a betrayal of the life his father laid down for his. Only Askeladd seems to be free of such conflicts, living for its own sake – but he’s living a lie just the same, using men he says he hates to slaughter indiscriminately. Even for a man like Askeladd, I suspect life has meaning – and that be believes there are existential consequences for the choices he makes, even if limited to this world.

Jindujun93

October 14, 2019 at 6:44 pmEven knowing what was coming as a reader of the manga, this was hard to watch. I actually expected they’d tone it down in the anime, at least a little – but nope, WIT went the full mile here, and what a glorious episode it did end up being, even if it was hard to stomach.

Elear

October 14, 2019 at 7:03 pm“Only Askeladd seems to be free of such conflicts, living for its own sake – but he’s living a lie just the same, using men he says he hates to slaughter his own people.”

They’re already back in England though (the anime could have made this clearer tbh), so those people weren’t Welsh. So Askeladd could at least be a tribalist. If they belong to his tribe, i.e. are Welsh, he cares about them and wants to protect them. If they’re not, then it’s fair game to kill them. Most men were like that then and some still are today. Of course, he may also simply have been lying about hating Norsemen and/or wanting to protect the Welsh. As you said last week, it’s not wise to take anything as a certainty with this man at this point in the story.

As for the final scene with Anne, I think it was meant to show how, despite the brutality and wickedness of their deeds, the vikings’ fearlessness and complete disregard for divine judgment and retribution appeared awe-inspiring and even in a way liberating to a God-fearing young girl like her. A powerful scene to be sure, with beautiful backgrounds (as usual) by WIT.

Guardian Enzo

October 14, 2019 at 8:10 pmI don’t know. I’m just vibing that Nihilism is too simplistic an explanation for Askeladd – he’s too complicated an individual for that to be the governing philosophy of his life.

Yukie

October 14, 2019 at 8:45 pmI don’t really like that they’ve translated “doki doki-suru” to feeling elated. The translation in the manga was much more literal, “my heart is/was pounding,” and there were fewer close-ups to Anne’s actual facial expressions throughout her monologue, so it’s very much left up to the reader to interpret.

Apart from that, I’m once again awe-struck by the stunning visuals and direction of this episode.

Marty

October 14, 2019 at 9:33 pmOh man, THIS is what I love about Vinland Saga, not much happened plot progression-wise, but at the same time there was so much subtext and so many layers.

I feel like the reason why the priest was interested and impressed with Thors but not the comradeship of the brothers is that the brother’s love was conditional (they had each other’s backs, but no one else’s), but Thors’ wasn’t. It didn’t matter to him whether is enemies were honorable men or murderous bandits, he nevertheless saw value in preserving their lives, despite being complete strangers. And at the end of the day, when it came down to it, he sacrificed himself rather than see others lose their lives, if that isn’t unconditional and selfless love, I really don’t know what is.

The interesting thing about this ending is that we’ve already seen this before. Askeladd and his men have been raiding and killing for YEARS, even before Thorfinn joined them. The only difference is that we spent some time getting to know the victims this time, but that’s about it. The killings may have been more systematic this time around, but it’s always been a necessary evil of the Viking lifestyle.

I believe Askeladd is being driven by his mission to save the Welsh (Mercia is an Anglo-Saxon kingdom, so there’s no moral conundrum regarding his loyalty to his people there), not any particular “-ism.” Let’s remember for a second that he only has 104 men, as far as he knows he’s being hunted by Thorkell’s 500 ( God knows how many villages THEY had to pillage), and he’s in hostile territory. This is essentially a covert operation, and Askeladd was being calculating in a merciless war.

DonkeyWan

October 15, 2019 at 12:11 amI believe the final scene with Anne can be interpreted differently. So shocked and horrified by the brutality of the act by the act of the Danes that the only happiness she can take from the brutality of the attack is to believe her family is now safe with God, protected and happy. The implication being of course, that she will soon join them. The final scene, where she lies collapsed in the snow, but suddenly aware of someone near by shows that there are other plans for her.

Stöt

October 16, 2019 at 9:22 amShe suspected she’d go to hell though. She feared the devil, but doomed her soul with theft. So I don’t think she thought she’d join her family in death.

Michael

October 15, 2019 at 10:02 amI think Askeladd’s ordered slaughter at the village is different from a typical sacking of the town by Danes. It is very much calculated – a sacrifice for the larger good (which in his mind is the non-aggression pact that protects Wales). I think the Danes might start to question Askeladd. Not just because of this, but because they are slowly being forced to act more as a disciplined military force than a party out for loot.

I think this is showing a couple of different contrasts. First, in some ways the Danes and the Christians are a bit a like. They pursue their lives for reasons in and of themselves – getting into Valhalla; honor, glory, and pleasures for the Danes and getting into Heaven; pietism for the Christians (also some honor and glory too, but that’s not shown here!).

Askeladd is different; how is living is not comporting with his values, rather he lives in a certain to way to obtain an ultimate goal. He is engaging in terrible bloodshed as a calculated choice, unlike many of the Danes.

I think the big question of the story is how do the young choose to live? How does Thorfinn choose to live? How about Canute? Will they go the path of Askeladd or of the other Danes and Christians, or is there another option…?