I suppose it’s only natural that the finale of The Great Passage has left me in a tremendously reflective mood, because it’s one of the more reflective series you’ll ever see. It seems timely, as well, despite it’s being adapted from a 5 year-old novel that was made into a live-action film two years later. That’s fitting, too, because one of the many themes of Fune wo Amu is that truly important things are timeless – they outlive us, but through the work of our lives we transcend our ephemeral existence and live on in those who follow us.

I suppose it’s only natural that the finale of The Great Passage has left me in a tremendously reflective mood, because it’s one of the more reflective series you’ll ever see. It seems timely, as well, despite it’s being adapted from a 5 year-old novel that was made into a live-action film two years later. That’s fitting, too, because one of the many themes of Fune wo Amu is that truly important things are timeless – they outlive us, but through the work of our lives we transcend our ephemeral existence and live on in those who follow us.

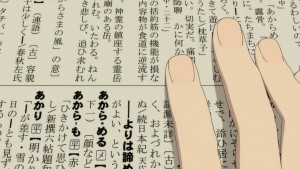

The cast of Fune wo Amu seems to exist in a kind of time warp themselves. They do work that most modern humans would probably see as a holdover of another time. They barely use technology in their work – before or after the 13-year time skip in the middle of the series. Some have criticized this aspect of the series as unrealistic, but for me, it’s an essential part of who these people are and what they do. Yes, they could use photographs instead of drawn illustrations, just as shows like this could be animated via CGI rather than hand-drawn and the music of Mozart could be reproduced digitally rather than by human hands and breath on wooden and brass musical instruments. But simply because something can be done doesn’t mean that it should be done.

The cast of Fune wo Amu seems to exist in a kind of time warp themselves. They do work that most modern humans would probably see as a holdover of another time. They barely use technology in their work – before or after the 13-year time skip in the middle of the series. Some have criticized this aspect of the series as unrealistic, but for me, it’s an essential part of who these people are and what they do. Yes, they could use photographs instead of drawn illustrations, just as shows like this could be animated via CGI rather than hand-drawn and the music of Mozart could be reproduced digitally rather than by human hands and breath on wooden and brass musical instruments. But simply because something can be done doesn’t mean that it should be done.

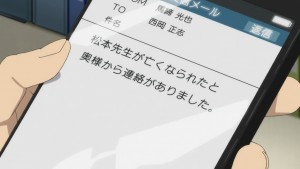

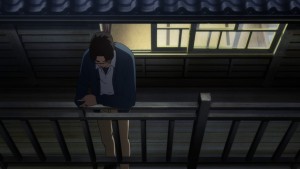

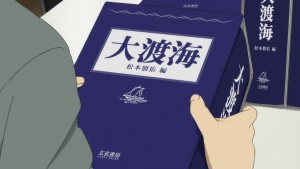

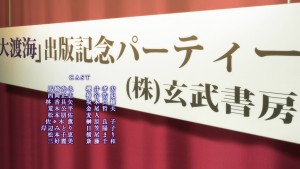

There was very little in this final episode that came as a surprise to me. Despite that, however, it still hit me like a ton of bricks – especially the beautiful, powerful and dignified final five minutes. That was as good as any anime this season or this year – a quiet and sober statement of defiance and purpose and an embrace of the power of human decency. I think the poet in me always knew Matsumoto-sensei wasn’t going to make it to see “The Great Passage” finally published, but it was important that he make it clear to us why that wasn’t something tragic but rather itself part of an even greater passage.

There was very little in this final episode that came as a surprise to me. Despite that, however, it still hit me like a ton of bricks – especially the beautiful, powerful and dignified final five minutes. That was as good as any anime this season or this year – a quiet and sober statement of defiance and purpose and an embrace of the power of human decency. I think the poet in me always knew Matsumoto-sensei wasn’t going to make it to see “The Great Passage” finally published, but it was important that he make it clear to us why that wasn’t something tragic but rather itself part of an even greater passage.

3000 pages is a lot of words, but that means little when stacked up against the sheer weight of human lives that went into producing them. I’ve said it many times, but The Great Passage is a story of passion – don’t be fooled by its quiet demeanor. Everyone who gave their lives over to producing the dictionary did it as a labor of love – for the work itself and yes, for their co-workers too. They managed to live their lives in the meantime – Nishioka and Miyoshi did get married after all, and have two kids to boot. But I would argue that the work gave these people lives even more meaning than their private lives, because rather than connecting them to a spouse or children, it connected them to the entire human race.

3000 pages is a lot of words, but that means little when stacked up against the sheer weight of human lives that went into producing them. I’ve said it many times, but The Great Passage is a story of passion – don’t be fooled by its quiet demeanor. Everyone who gave their lives over to producing the dictionary did it as a labor of love – for the work itself and yes, for their co-workers too. They managed to live their lives in the meantime – Nishioka and Miyoshi did get married after all, and have two kids to boot. But I would argue that the work gave these people lives even more meaning than their private lives, because rather than connecting them to a spouse or children, it connected them to the entire human race.

I was especially struck by something Matsumoto-sensei said to Majime and Araki during their visit, just before breaking the news that he’d been diagnosed with cancer. He described how dictionary publication was often publicly supported in Western countries – something which seems quite a good thing. Matsumoto then asked Majime why he thought this was, knowing that because he was talking to a kindred spirit he’d get the right answer. But he then described why this might not be such a good idea – there would be temptation for those in power to influence the content to suit their own ends.

I was especially struck by something Matsumoto-sensei said to Majime and Araki during their visit, just before breaking the news that he’d been diagnosed with cancer. He described how dictionary publication was often publicly supported in Western countries – something which seems quite a good thing. Matsumoto then asked Majime why he thought this was, knowing that because he was talking to a kindred spirit he’d get the right answer. But he then described why this might not be such a good idea – there would be temptation for those in power to influence the content to suit their own ends.

“Words and the heart of those who use them must remain free. Even with our scarce funding, we are individual people, not a nation. We spend our lives editing the dictionaries. Let us take pride in this.” In the softly-spoken words of a dying old man, Fune wo Amu makes a bold and revolutionary statement that rings loudly in the ears of anyone who hasn’t closed their minds to them. It’s a shot across the bow of those who would divide and demean the human race, no more and no less. If that dichotomy of style and substance doesn’t sum up Fune wo Amu, I don’t know what does.

“Words and the heart of those who use them must remain free. Even with our scarce funding, we are individual people, not a nation. We spend our lives editing the dictionaries. Let us take pride in this.” In the softly-spoken words of a dying old man, Fune wo Amu makes a bold and revolutionary statement that rings loudly in the ears of anyone who hasn’t closed their minds to them. It’s a shot across the bow of those who would divide and demean the human race, no more and no less. If that dichotomy of style and substance doesn’t sum up Fune wo Amu, I don’t know what does.

Matsumoto-sensei’s statement of purpose doesn’t just invite us to consider its meaning – it demands it. The idea of “individual people, not a nation” is as anathema to the core of Japanese culture as it gets, but Japan is currently in a time of rising nationalism and militarism. Fune wo Amu was always about the importance of words as a means to connect people to each other – not Japanese people, just people. In America we’ve seen the rise of a demagogue who demonizes those who oppose him personally and demonizes entire groups as a means of fostering the resentment he rode to power (which is pretty much what all fascists do). If Fune wo Amu is anachronistic in a good way, it’s important to remember that there are many elements of human society that don’t change that are far less desirable. Progress always involves backwards steps as well as forwards – somehow, we need to find the wisdom to hang on to the elements of the past make us human even as we jettison that which makes us savages. Needless to say, progress is a work in progress.

Matsumoto-sensei’s statement of purpose doesn’t just invite us to consider its meaning – it demands it. The idea of “individual people, not a nation” is as anathema to the core of Japanese culture as it gets, but Japan is currently in a time of rising nationalism and militarism. Fune wo Amu was always about the importance of words as a means to connect people to each other – not Japanese people, just people. In America we’ve seen the rise of a demagogue who demonizes those who oppose him personally and demonizes entire groups as a means of fostering the resentment he rode to power (which is pretty much what all fascists do). If Fune wo Amu is anachronistic in a good way, it’s important to remember that there are many elements of human society that don’t change that are far less desirable. Progress always involves backwards steps as well as forwards – somehow, we need to find the wisdom to hang on to the elements of the past make us human even as we jettison that which makes us savages. Needless to say, progress is a work in progress.

In anime as in life, progress is a matter of fits and starts. Coming off its strongest year since 2012, anime is staring into the maw of a 2017 that appears at this remove to be a creative wasteland of repetition, pandering and exploitation. And even as it finished a year which saw it flash more ambition than it had for some years, NoitaminA too seems to be headed for dark times. Fune wo Amu is not only an anachronism in terms of its characters, but its very existence. It’s a relic of another time for NoitaminA, and it’s impossible not to wonder if it represents the last of its breed. It’s not the best show NoitaminA has ever produced but it is as true as any to what it once represented.

In anime as in life, progress is a matter of fits and starts. Coming off its strongest year since 2012, anime is staring into the maw of a 2017 that appears at this remove to be a creative wasteland of repetition, pandering and exploitation. And even as it finished a year which saw it flash more ambition than it had for some years, NoitaminA too seems to be headed for dark times. Fune wo Amu is not only an anachronism in terms of its characters, but its very existence. It’s a relic of another time for NoitaminA, and it’s impossible not to wonder if it represents the last of its breed. It’s not the best show NoitaminA has ever produced but it is as true as any to what it once represented.

We seem, then, to be headed into a dark tunnel whose end is not in sight – as people, as fans of anime. The Great Passage makes a dignified, respectful case for defiance – it urges us to stand true to what we know is right, and to resist those who would drag us from the true path. As individual humans we’re small, our lives a blink of an eye – but collectively we can move mountains, either for good or for evil. We must be true to ourselves by accepting that we’re powerless without others – and only through words may we build the connections which move humanity towards enlightenment. Those who live their lives in their service of this idea – be they dictionary editors, authors or anime producers – deserve our gratitude and respect, and they certainly have mine.

We seem, then, to be headed into a dark tunnel whose end is not in sight – as people, as fans of anime. The Great Passage makes a dignified, respectful case for defiance – it urges us to stand true to what we know is right, and to resist those who would drag us from the true path. As individual humans we’re small, our lives a blink of an eye – but collectively we can move mountains, either for good or for evil. We must be true to ourselves by accepting that we’re powerless without others – and only through words may we build the connections which move humanity towards enlightenment. Those who live their lives in their service of this idea – be they dictionary editors, authors or anime producers – deserve our gratitude and respect, and they certainly have mine.

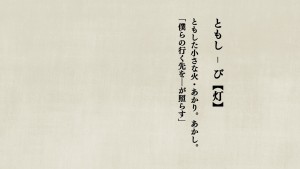

End Card: “Light”

HoTaRu

December 23, 2016 at 10:50 pmYou said it all with this review. I thoroughly enjoyed this show from start to finish and was blown away with how incredible the ending was. They managed to wrap things up in a heartfelt and emotional way that gave me everything I could have wanted and more. I was especially moved by Matsumoto-sensei’s words and how they affected Majime. Seeing Nishioka with his daughters after Matsumoto-sensei was talking about the circle of life was a perfectly timed scene and put a lump in my throat. Every aspect of this show blended to create a nearly perfect finished product. This kind of show is why my love of anime never fades away.

Flower

December 23, 2016 at 11:42 pmWell written Enzo … and yes … I also was quite surprised by Matsumoto’s “shot across the bow” as you put it … especially in the light of other characteristics that Japan has historically lauded, but even more so as a message for today.

I just finished watching the Live-Action movie of the franchise, and actually was kinda surprised. I thought the anime was much better in presenting the beautiful and dignified nature and quality of the characters. To be able to present them so effectively impressed me, and is all the more reason to treasure the lovely adaptation this series is.

JJ

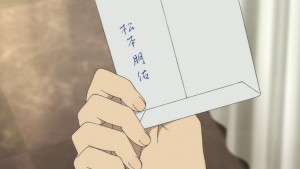

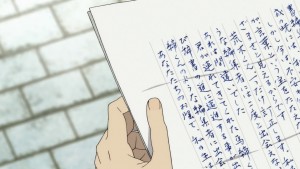

December 24, 2016 at 12:07 amMajime reading Matsumoto’s letter was a pleasant cap to 2016, as powerful a scene as anything I’ve seen this year. Given that that includes the likes of Yotaro’s Dekigokoro, Kayo’s breakfast, Reigen 1000%, Kakeru finding his mother’s phone, Avilio & Nero’s last roadtrip, Kaizaki’s senpai, Tora’s sacrifice, Yuri & Victor’s kiss …

and that’s just the anime covered on this blog! I’d add another couple to that list.

The Great Passage truly has been a pleasure to watch and a fitting way to finish the year. As dire as 2017 may be (in anime and otherwise), I will do my best to take Matumoto’s lesson on citizenship to heart.

Zilla

December 24, 2016 at 6:26 amOn the series: While I wasn’t expecting a typical anime with this show, I was expecting a work/friendship show focusing on Majime and Nishioka, what we got was so much better than that. There is definitely a spot on my shelf for this when it comes out in disc form. And I will add this to my list of anime to recommend to those who say “Anime is just cartoons, and it’s all the same. Big eyed girls doing cute things or boys powering up.”

On the episode: I had braced myself for Matsumoto dying, either just before of just after publication. I got a little misty when it happened, but that was okay. Majime quietly breaking down about it out on his porch just about wrecked me though, and then the letter finished me off. From the changing expressions on the woman’s face (who was she? wife? daughter? caretaker?) before Matsumoto told them about his prognosis to the way the party continued while Majime was reading the letter . . . it was all masterfully done.

Guardian Enzo

December 24, 2016 at 9:00 amDefinitely his wife.

Earthling Zing

December 24, 2016 at 8:22 amI didn’t expect to be hit that hard by the ending. This episode pretty much sums up why a show with such a traditional plot had to be about dictionaries: dictionaries contain words which transcend the time and passing of human beings.

Conclusion

December 24, 2016 at 10:17 amI must be in the minority then, because I think it rarely helps the narrative to have characters transparently promoting the author’s political views and Matsumoto doing it here was no exception, especially since this took place in a deathbed situation. (Of course there are stories where politics can be a very organic component, but not here in my opinion. While it could perhaps be argued that this was philosophy, not politics, the fact that people talking about the show use those statements as a cue to insert political commentary of their own seems to indicate otherwise.) I don’t particularly disagree with what Matsumoto was saying, but it was laid on a bit thick and this detracted from an otherwise tasteful scene.

All-in-all a good show, although unlike Enzo I could have done with less nostalgia for nostalgia’s sake and technologial retrogradism for its own sake – I’m positive the underlying ideas could have carried the show even if those aspects were toned down. And I sure hope Majime and Kaguya can and will have children as well, because there was a certain listlessness to them that made me worry. They could use some of that vitality evident in Nishioka’s family.

Guardian Enzo

December 24, 2016 at 10:24 amI would strongly argue that what Matsumoto was talking about wasn’t politics – at least if one understands what that term actually means. If we’re in a world where it’s considered offensive to make the case for an ethical philosophy we really are fucked as a culture.

Conclusion

December 24, 2016 at 11:58 amI don’t understand this aggressiveness. I didn’t take offense to anything, although you certainly seem to have, for reasons that escape me at the moment. Was I wrong to point out that you inserted your political views on this cue? I’ve seen others do the same elsewhere, so there’s at the very least a politically inducive element to these musing expressed by Matsumoto.

As for this particular philosophy, the concern that the goverment would seek to influence the content of dictionaries funded by the state seems trendy enough, but it’s not an inevitability; nor is private funding a guaranteed sefeguard against the contents getting filtered through the bias of the editors themselves or higher-ups in the publishing company (plenty of these firms tend to have clear political leanings, the same way newspapers often do). I happen to live in a country were most big national language dictionaries are funded through taxpayer money, and I don’t believe I’ve perceived government interference in the contents – and any such attempt would leak in no time and the press would have a field day. I’ve seen plenty of examples of editorial quirks and bias, though.

But how much I agree with Matsumoto’s(/the author’s) statements is not that relevant here, it just jarred me that while most of the struggle the team has been through has had to do with their own company, a final message would suddenly caution against government interference instead. If this topic had been touched upon before, it might not have felt out of place, but in this case it did for me. And since it didn’t fit the narrative, and has prompted political comments by the audience, I called it political. (But of course it’s entirely possible that I simply do’n’t understand what the term actually means, as you kindly pointed out.)

Simone

January 2, 2017 at 2:13 amOne thing that left me wondering was the use of the term “overseas” when talking about governments sponsoring the publishing of dictionaries (and influencing their contents). To me that sounded less like “Western countries” and more like “China”. In that perspective what was said was much more straightforward – merely a statement about how some totalitarian governments or other degrees of dictatorships/oligarchies may handle the task to suit their needs.

juju et son chat

December 31, 2016 at 3:47 amUsually I’d never watch anime such as this one – mostly because noone ever talks about these. But then I found your website and started reading your review. And after watching the whole thing – well I have to admit it really – but really – was worth the ride !

And thumbs up for your reviews – I’m glad it made me feel like trying this masterpiece

Guardian Enzo

December 31, 2016 at 4:52 pmMerci! Always nice to hear from folks who try something they otherwise might not based on my recommendation (as long as they end up liking it…).