|

|

|

|

|

|

If there’s one word that springs to mind when contemplating Miyazaki Hayao’s final film, it would be “difficult”. And I’ve contemplated it a lot. I saw it in Japanese soon after its theatrical premiere, and seeing it a second time with subtitles has done nothing to help me clarify my feelings about it – if anything, I’m more puzzled than ever. Both as a capstone to the most artistically ambitious and successful career in animation history and as a standalone statement, Kaze Tachinu is an enigma.

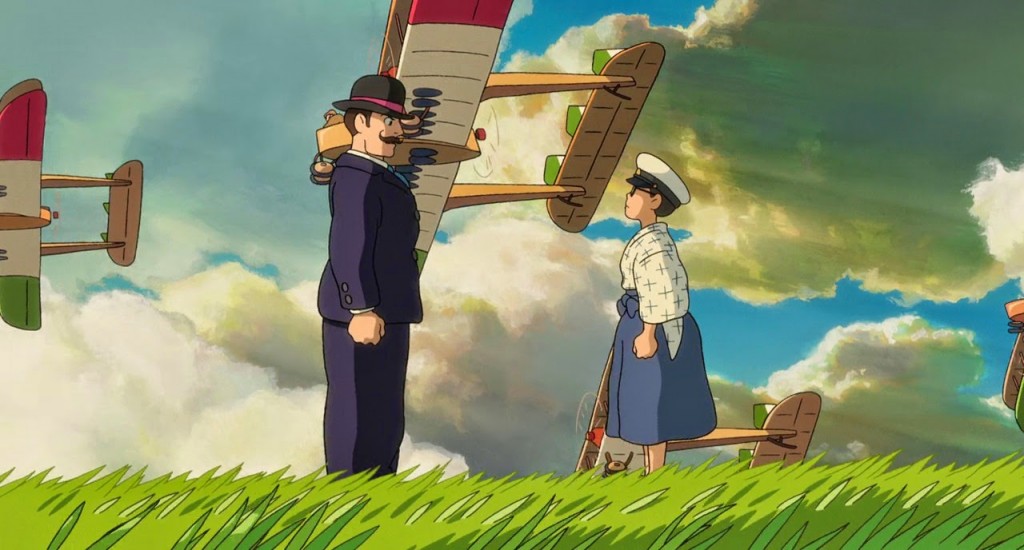

Certain things can be stipulated to, I think. The Wind Rises is a staggeringly beautiful work, both in sound and vision. Miyazaki works with his usual musical partner here, the peerless Joe Hisaishi, and the first frames are the film are accompanied by the composition “Journey (Dream of Flight)” from Hisaishi-san, a gorgeous Italianesque piece that’s interwoven throughout the entire film. Rarely have I encountered a piece of music that so suits the mood of a movie – it speaks eloquently of flight. Flights of imagination, of fancy, of euphoria and sadness. Hisaishi’s score – and especially this piece – are like the wind that Miyazaki’s vision soars upon for two hours.

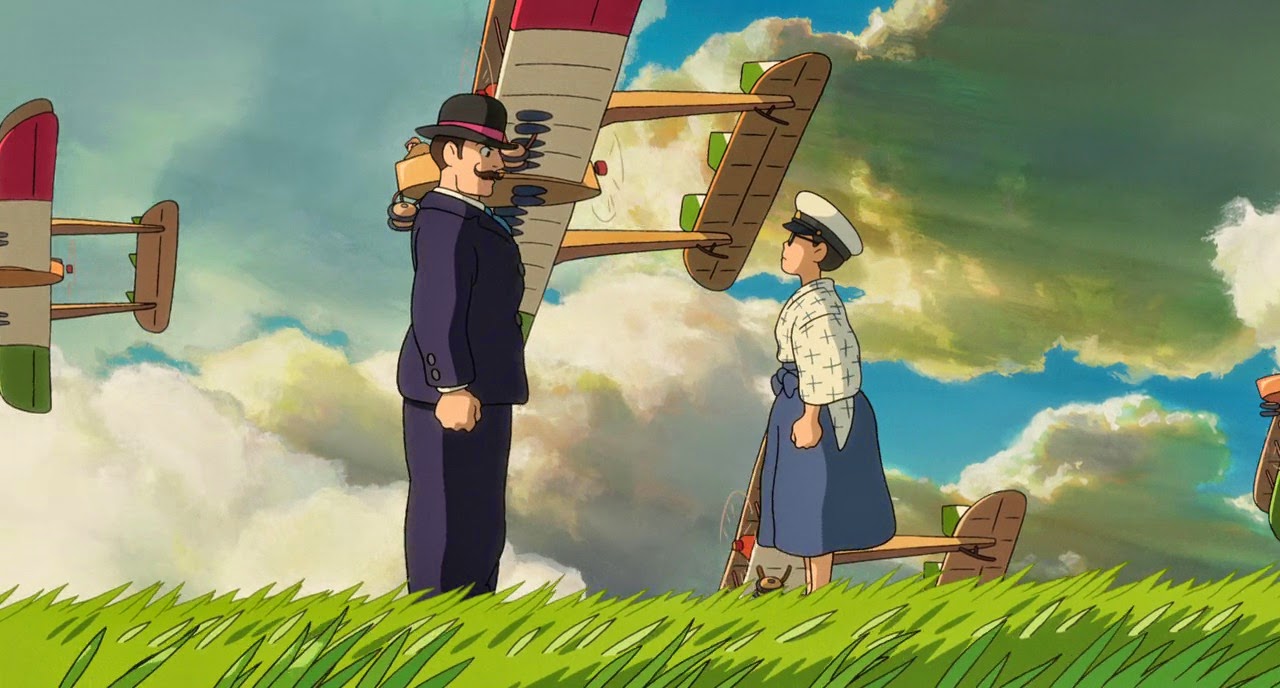

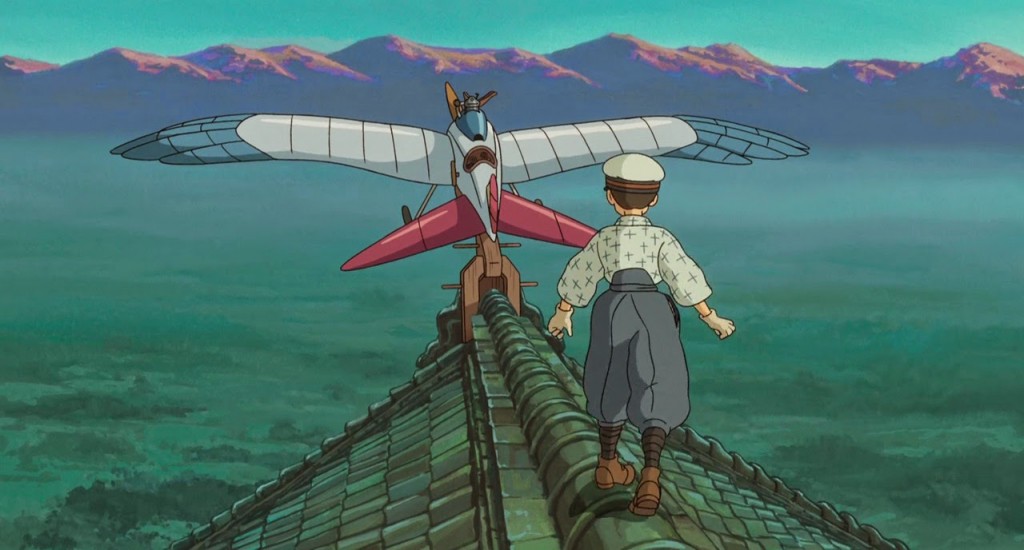

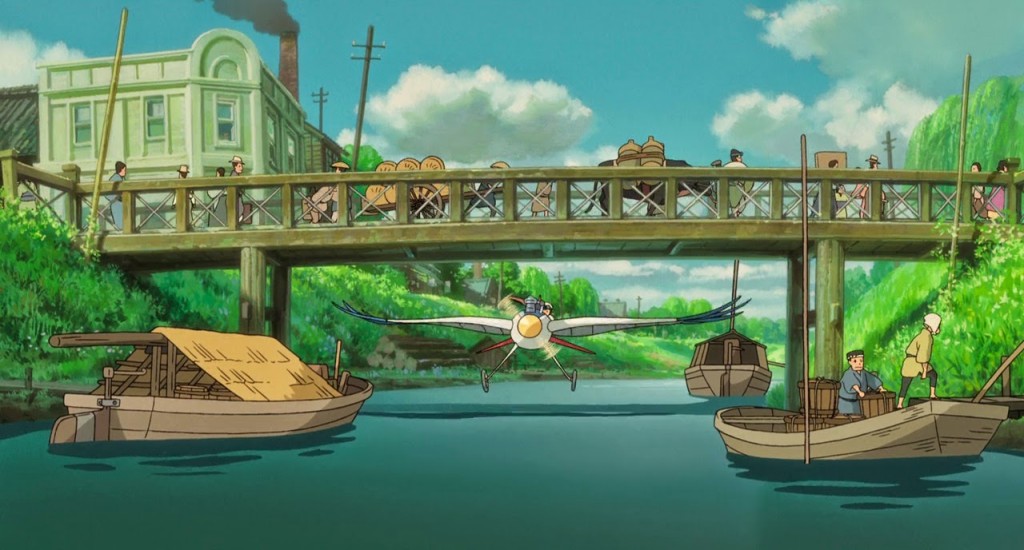

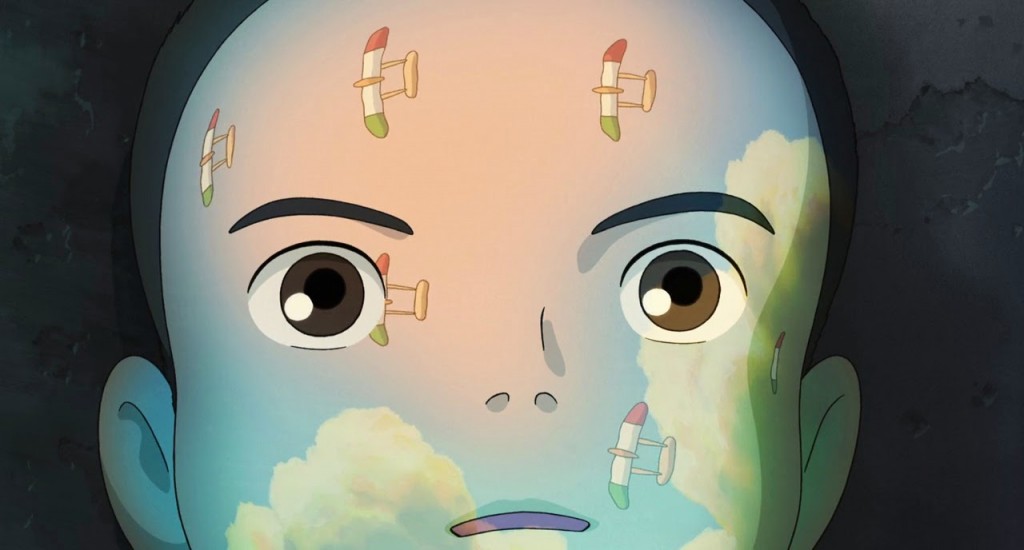

And what a vision it is. As anyone who loves Miyazaki-sensei’s work could tell you, the master has a lifelong obsession with flight and airplanes. We’ve seen it expressed in some form in almost all of his movies, most specifically Laputa: Castle in the Sky and Porco Rosso. While Kaze Tachinu is less overtly fantastical than those films, it still takes the form of a dream. Sometimes quite literally, as the movie’s protagonist shares his dreams with the likes of boyhood heroes and the love of his life – but the entire story has the air of a dream to it, a musing on the way dreams allow us to soar above our limitations and experience true beauty.

If there’s one sequence in the film that’s most striking, however, it’s more of a nightmare – Miyazaki’s depiction of the Great Kanto Earthquake of 1923. The immediacy of feeling he’s able to communicate with this slightly surrealistic set piece is remarkable, a testament to his genius. Even in this horror, though, there is beauty – for it’s in the aftermath of this disaster that Miyazaki’s hero forms the connection with the woman he’ll come to love. This, too is a theme we see repeated over and over in The Wind Rises – the inseparability of light and darkness, of beauty and horror. And it’s here in which the difficult questions that make the film so difficult reside.

Nominally this is the life story of Horikoshi Jirou (Anno Hideaki, Kaburagi Kaichi as a child), the man who designed the legendary A6M “Zero” fighter plane for Mitsubishi. But the personal side of the story is almost completely fictionalized – loosely based on a pre-WW II novel by Hori Tatsuo (also titled Kaze Tachinu) which has no connection to Horikoshi. This part of the film delivers some of its most effecting moments, mostly centered on Horikoshi’s love for a young woman named Satomi Naoko (Takimoto Miori, Iino Mayu as a child). Horikoshi and Naoko are on a train from Fujioka to Tokyo when the earthquake hits, and his bravery saves the life of her servant. Once she’s safe he leaves without any request for reward, but we know this is a connection that will be renewed in the future.

Without a doubt, the love story between Jirou and Naoko is the most conventional part of the film – yet it’s very engaging (Miyazaki’s decision to cast his friend Anno – the legendary Evangelion director whose previous seiyyu experience consists of playing a cat in FLCL – as Jirou is an interesting one. Anno-san is naturalistic and unmannered to the point of being somewhat flat – like so much in Kaze Tachinu, I have a hard time deciding how I feel about it). Naoko suffers from tuberculosis (as many did in those days) and to call this a bittersweet romance would be an understatement. But ultimately the part of the story that springs from Hori’s novel is pretty straightforward, essential to the movie’s existence but not at the heart of it. And it’s the other side of Kaze Tachinu, that which dances more closely with history and Horikoshi’s true life story, that’s both controversial (especially in Japan) and challenging.

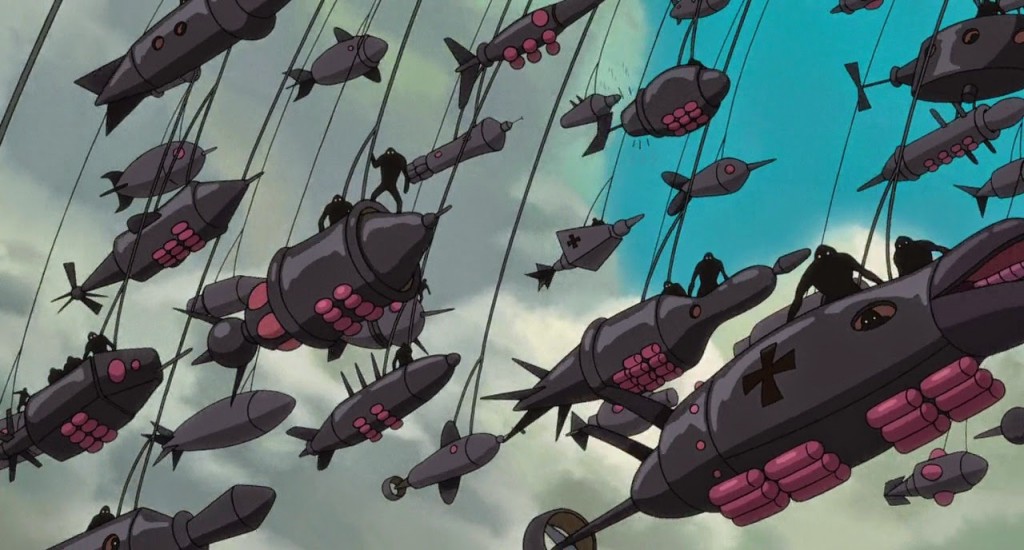

It’s fairly well-known that Miyazaki Hayao is a pacifist. So why, then, choose to make his last film about the man whose planes destroyed Pearl Harbor, and were essential to the Japanese war effort? Horikoshi too hated war, and thought the Japanese government foolish to pursue war with America – his journals from the time bear this out. Yet design the planes he did, knowing full well what they would be used for. Miyazaki said the idea for Kaze Tachinu was inspired by a single quote from Horikoshi – “I just wanted to make something beautiful.” And while I’ve no reason to doubt Horikoshi-san at this word, for me at least the answer isn’t that simple.

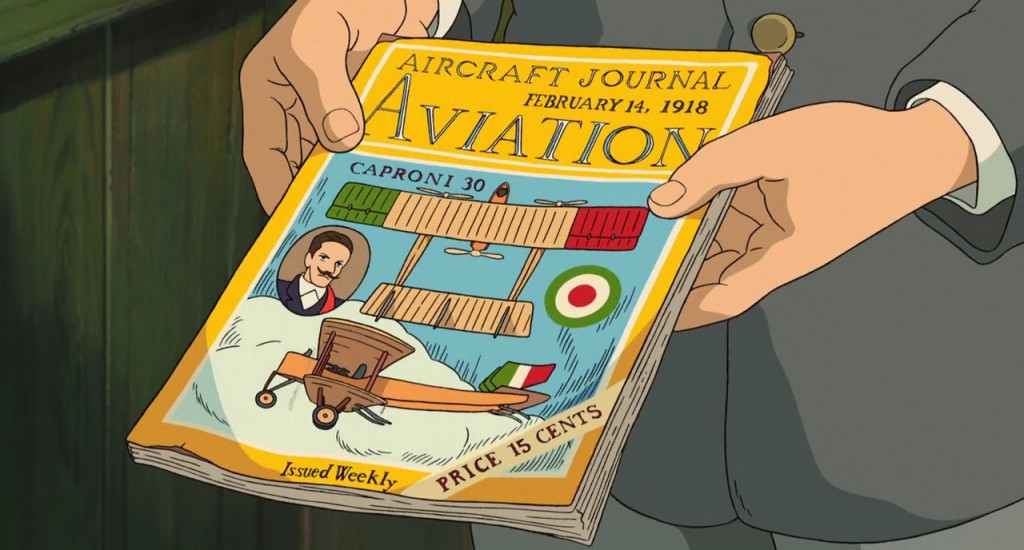

Fundamentally, the entire raison d’etre of The Wind Rises boils down to a simple question – is it possible to separate the man from the way in which that which he created was used? It’s very possible that Miyazaki saw this film as an opportunity to spur debate over Japan’s plans to re-militarize (which has been a simmering issue here for decades and is now coming to a head under nationalist premier Abe Shinzou). But he also opened himself up to charges that he was romanticizing Horikoshi’s role – sugarcoating the truth to cast him in a better light. Miyazaki uses the aforementioned dream sequences – mostly in the company of Jirou’s boyhood hero, Italian aircraft design pioneer Giovanni Caproni (Nomura Mansai) – to give form to Jirou’s imagination and communicate the nature of this desire to create beauty. Caproni’s involvement hits very close to home – it was his plane that Miyazaki named Studio Ghibli after.

The movie is full of this sort of equivocation. We have a trip to Germany to visit Mitsubishi’s licensed partner Junkers, a decade ahead of Japan in aircraft design. The Germans are condescending towards their Japanese “guests”, but founder Hugo Junkers allows Jirou and his best friend Honjou (Nishijima Hidetoshi) to see inside the legendary G.38 “Flying Wing” and even take a test flight. Junkers was another pacifist – a genuine anti-war internationalist who had his company stolen from him by the Nazis and died penniless in 1935. We also meet a sympathetic German named Castorp (Stephen Alpert – another non-actor, this time the head of Ghibli’s overseas division) at the rural hotel where Jirou and Naoko reconnect years later. Castorp (the name is taken from the protagonist of Thomas Mann’s The Magic Mountain) warns of impending disaster for Germany and Japan, and sings charming German ballads at the hotel piano while smiling beatifically (if a little impishly). It’s later implied that he fled Japan with the country’s thought police hot on his tail.

That sequence at the hotel – full of innocent romance and beautiful scenery, of soaring paper airplanes and Castorp’s charm – is one of the best in the movie. But it also contributes to the feeling that Miyazaki is trying very hard to convince us that there’s no blame to be assigned to his hero – that he was truly a victim at a time when victims were being made all over the world. Miyazaki makes it very clear that Japan was behind the times, in over its head, being dragged along by fools and scoundrels on a path of destruction. But what he never truly does is cast any independent judgment himself on Jirou’s role – and, more crucially, he never takes us inside Jirou’s process of judging himself.

Given the context of the film, that seems a surprising omission for Miyazaki. Perhaps it really is as simple in Miyazaki’s eyes as can be – Jirou is blameless. But that seems unlikely to me, as thoughtful a man as Miyazaki is. Perhaps he feels it’s not his place to judge Jirou, never having walked in his shoes. Perhaps he feels it would be disrespectful to show us what Jirou believes in this respect, when Jirou chose in real life to share little of that himself. Those are valid considerations, but for me it leaves Kaze Tachinu feeling like an incomplete portrait of its hero, fictionalized or otherwise. The film effectively stops at the beginning of the war, and the introspection for Horikoshi stops when the military takes delivery of the planes. The film is about the process and the dream, I get that – but it’s a conceit to pay so little consideration to what comes after.

“Airplanes are dreams.” Caproni tells Jirou in the movie’s final scene – fittingly, a dream. “Cursed dreams. Waiting for the sky to swallow them up.” This is as close as Miyazaki comes to framing Jirou’s life in moral terms, but it also strikes me that there may be a note of autobiography to it. This is Miyazaki-sensei’s final film, and he too is undeniably a dreamer above all else. He gives shape to the airplanes of his dreams, and to the castles and witches and forest Kami and boys and girls and conflicted men. Perhaps as much as it is about Horikoshi Jirou, Kaze Tachinu is a reflection by Miyazaki on his own dreams and visions – he releases them into the world, and once that happens he has no control over them. People will say of them what they will, and they exist independently of the man who created them.

That’s among many reasons why, despite whatever issues I may have with The Wind Rises, it strikes me as a very fitting way for Miyazaki to say goodbye. A fusion of a fictional novel and a biography, it may in the end be the most self-referential film Miyazaki has created. It’s the most “realistic” of his films in many ways, yet oddly the most fanciful as well – a work by an old man who’s always been very connected to the child that resides in himself and in all of us. Kaze Tachinu seems very much to be an impassioned tribute to the power of dreams, tinged with the frustration of knowing that reality will always place its own stamp on them. Even as we celebrate the man’s indispensable and glorious career, surely knowing that it’s coming to a close is cause for sadness as well. This film is a reminder that Miyazaki Hayao is a unique and irreplaceable artist, and we won’t see his like again.

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

ED: “Hikouki Gumo (ひこうき雲) by Yumi Matsutoya

|

|

|

|

|

|

thedarktower

June 28, 2014 at 2:14 pmit took him over 5 years to create this movie, and indeed it is probably his best works so far (obviously arguable because other works like Laputa, spirited away and others are masterpiece as well). but I think this movie really..express Miyazaki. there is a great complex of biography and life experience along with the surrealism world of the dreams. unlike his previous that contain somewhat prominent element of fantasy, this one is much more realistic and contain only the dream as something less usual than our world. thus, Miyazaki is able to create an interesting combination of both surreal and real.

Miyazaki slowly brings his philosphy along with the historical-biographical part.

we can see it through Jiro's character. despite all his failure and toughness of that period, he is still trying and dreaming. he wants to create something beautiful.

I can't say he is chasing Caproni, obviously that's not the case. but he is inspired by him and aim for a similar goal, of his own of course. and it is so important to see that Jiro is trying on his own and doesn't give up even. failure happens. Nanba Mutta said "an earnest failure has meaning". this exactly the case for Jiro.

indeed the movie rises some eyebrows as it focus on Jiro who after all is responsible for creating planes that became a killing machine in one of Humanity darkest periods.

Miyazaki is not running away from it. we see it because both Jiro and Caproni are aware of it somehow. but Kaze Tachinu isn't focusing on that point. he lets the viewers know that it's a point worth thinking about. yes, we should be aware what will be with our actions and creations. same happened to Alfred Novel with the Dynamite and founding the Novel price.

you know it's tough in our world..sometimes a man is good is something and wants to create or research something but he doesn't have the money or tools for it.does that mean Jiro was a bad person? I don't think so. Miyazaki neither. Jiro, along with his other friend, wanted to create a piece of metal that will fly. something beautiful.

there isn't black and white. there is light and darkness together. sometimes it's darker and in others it's brighter.

as for the love story, well in a way it's a typical Miyazaki because it ended up the way it ends, which was a bit hard. yeah, the love story between Naohoko and Jiro was convenient and a bit cliche, I can't deny it. but it performed so well with the art and music, the facial expressions and their difficulties. I loved it. it's a typical of him. especially in the end, I imagine Miyazaki himself stating those words of "we must live". and in the end, all of Jiro is..crying out loud and removing his seriousness. it's a double lesson for us as well – first, don't be really "cold" and serious all this time. second, we shouldn't be all that attached to work. Jiro's sister criticize him and despite he knew and accepted it..maybe things were better if would be different.

Ghibli and Miyazaki with another masterpiece work. I think it's Miyazaki best of all because it really represent all of his worldview to one movie. a great complexity that moved my heart. I am in awe for his works. even with more than 3 decades in the industry and despite this movie took so long, Miyazaki didn't lose a bit of his ability to excite us. a fantastic work with such an amazing art, sound and story. a truly masterpiece. thank you Miyazaki.

P.S

heard he got into SF hall of fame. he definitely deserved it.

BTW, despite Miyazaki stated his retirement (in the millionth time), never say never. he might return. yeah, it might not be same bla bla. it's Miyazaki. even in his absence these 5 years, he still produced an amazing movie. so who knows. that way or another he is still probably the greatest.

Ronbb

June 28, 2014 at 2:40 pmI was waiting for your post on the sub version of Kaze Tachinu, so thanks, Enzo — this is a very thoughtfully and passionately written post.

Yes, I love the work Joe Hisaishi, and the word "genuine" rushed through my mind a lot when I was watching this film. To me, this is the most genuine expression of Miyazaki-sensei's dream and passion for anime and airplanes. Yes, he didn't pass on any judgement on what happened and even fantasized the ugly side of history, but I guess that is his way of letting it all out in expressing what he has always loved — a genuine form of anime. I was a little conflicted before watching this film but felt very compelled and satisfied after watching it — I completed felt the amount of heart, soul, and love that Miyazaki-sensei and his crew have put into making this film, and for that, I'm touched. There are fantasized moments, but nothing is contrived for pandering any fandom. I'm amazed by how much you can be true to yourself and true to the making of anime and can still be commercially successful — this is so rare and too rare nowadays. Now that Miyazaki-sensei has really said good-bye to the anime world, I can't help but wonder if this phenomenon will become a legend…

I can't say enough how much I enjoyed Kaze Tachinu — partly because this is Miyazaki-sensei's last work of art — but I am also curious about what the next chapter of Studio Ghibli will bring. One last thought…this film may be Miyazaki-sensei's least suitable film for children because people in Kaze Tachinu smoked like chimney…

admin

June 28, 2014 at 2:44 pmThat doesn't have quite the same taboo here as it does in the States, but sure – I doubt you'd have seen every adult firing up like this in Ponyo. It's a reflection of the times – this was the 20's-40's – and the fact that Kaze Tachinu isn't really geared toward kids on any level.

Ronbb

June 28, 2014 at 4:07 pmNo, it's not. Not that other Miyazaki-sensei's films were meant for kids either, but yeah…perhaps the awareness of health hazard from smoking is a bigger deal here than in Japan.

Sir Christopher McFarlane

July 1, 2014 at 3:02 amIn those times smoking was good for you, as long as you had consumed Coke your whole life.

Flower

June 28, 2014 at 9:55 pmThat was an excellent review Enzo; I could tell it moved you and brought about a lot of reflection on many different levels.

Sometimes I think being able to present a work like this withOUT making an obvious assessment can be even more difficult than giving an outright "message", but in some cases the result could be more effective. I am not saying one is either, but I guess you feel it would have been more… umm… responsible, I guess?… to give the subject matter a clearer, obvious assessment considering contemporary issues?

admin

June 29, 2014 at 12:18 amI'm not going to judge Miyazaki here, just as he chooses not to judge Horikoshi, or put thoughts into his head. I just think it's interesting that he shows us no real introspection on Jirou's part, and I think that's a significant element of the film that should be pointed out.

Christeos Pir

June 30, 2014 at 1:51 pmThanks for putting into words what's been swirling around (and around, and…) in my head since watching "Kaze Tachinu." Well done once again.

admin

June 30, 2014 at 2:28 pmYou're very welcome. I love anime that make me mentally grind as much as this movie does.

Millenia

July 1, 2014 at 8:38 amA pleasure reading this word-perfect review Enzo. I see a lot of discussion around the controversies of this film, but I think you've pin-pointed the most significant one (considering who is in the director's seat). I feel that despite the lack of introspection, Miyazaki leaves a few visual clues that speak of the indifference many may have felt towards Japan's war effort at that time, but that ultimately war is a shell of living and a fruitless endeavor. Dreams belong to the individual, so collective morality is perhaps meant to be viewed outside the frame of this painting?

I'm partial to Miyazaki's fanciful depictions of the magic of dreams, so I was glad to see that side shine through in an otherwise grounded film. I think what makes this film sing as a swan song of Miyazaki is that doesn't just speak about dreams, it is a fully realized one.

admin

July 1, 2014 at 8:48 amIndeed, well-put. The more I mull this one over the more convinced I am it's highly autobiographical, and indeed that's largely why Miyazaki-sensei chose it as his swan song.