|

|

|

“From up on Poppy Hill”

One thing’s for sure – it can’t be easy being Miyazaki Gorou.

Anyone who pays close attention to anime in its theatrical form has spent plenty of time listening to directors being called “The next Miyazaki”. Makoto Shinkai (cold) and Hosoda Mamoru (a little warmer) seem to be the most popular victims of this particular curse (or recipients of the compliment, depending on your perspective) but in point of fact, there is a next Miyazaki out there – in name and genetics, at the very least. But few seem to want to foist that label on Gorou-sensei, for better or for worse.

If it weren’t hard enough having to bear the weight of the Miyazaki name and legacy, Gorou has also had to deal with some painful personal issues as well. Hayao-sama has stated publicly that he was a terrible father, rarely spending time with his children. And when Gorou’s directorial debut Gedo Senki, an adaptation of Ursula K. LeGuin’s “Wizard of Earthsea”, was being finalized, Hayao was openly critical of his son, saying he wasn’t ready to be a director and he’d been given the honor too soon. He then went on to criticize the film itself, which had to hurt his son pretty badly. Gorou has generally taken the high road and not returned his father’s fire publicly – surely a wise decision – but when Gedo Senki received mediocre reviews and performed poorly at the box office by Ghibli standards, the long knives were quick to appear in the hands of the press.

If it weren’t hard enough having to bear the weight of the Miyazaki name and legacy, Gorou has also had to deal with some painful personal issues as well. Hayao-sama has stated publicly that he was a terrible father, rarely spending time with his children. And when Gorou’s directorial debut Gedo Senki, an adaptation of Ursula K. LeGuin’s “Wizard of Earthsea”, was being finalized, Hayao was openly critical of his son, saying he wasn’t ready to be a director and he’d been given the honor too soon. He then went on to criticize the film itself, which had to hurt his son pretty badly. Gorou has generally taken the high road and not returned his father’s fire publicly – surely a wise decision – but when Gedo Senki received mediocre reviews and performed poorly at the box office by Ghibli standards, the long knives were quick to appear in the hands of the press.

Publicly at least, father and son appear to have patched things up – or at least declared a cease-fire. For Gorou’s second feature, Kokuriko-zaka kara, Hayao-sensei himself wrote the script – adapted from a 30 year-old shoujo manga by Takahashi Chizuru and Sayama Tetsurou. There was no public bickering during production or after release, and “Poppy Hill” was released to generally favorable reviews and went on to be Japan’s top-grossing film of 2011. It also won the Japanese Academy Award for best animated film of 2011. So all in all, things seem to have improved greatly for the younger Miyazaki. And now that the film has arrived on Blu-ray at last (it will also be receiving a brief U.S. theatrical run this summer), we can see and decide for ourselves.

Publicly at least, father and son appear to have patched things up – or at least declared a cease-fire. For Gorou’s second feature, Kokuriko-zaka kara, Hayao-sensei himself wrote the script – adapted from a 30 year-old shoujo manga by Takahashi Chizuru and Sayama Tetsurou. There was no public bickering during production or after release, and “Poppy Hill” was released to generally favorable reviews and went on to be Japan’s top-grossing film of 2011. It also won the Japanese Academy Award for best animated film of 2011. So all in all, things seem to have improved greatly for the younger Miyazaki. And now that the film has arrived on Blu-ray at last (it will also be receiving a brief U.S. theatrical run this summer), we can see and decide for ourselves.

I wasn’t one of the many piling abuse on Gedo Senki, for the record – it was a flawed film, undeniably, but had some moments of true beauty (and as a huge fan of the books, I was a tough audience). But let there be no mistake, Kokuriku Zaka Kara is clearly better. It’s a Ghibli film through and through, but quite unlike any Hayao-sensei has directed in recent years. It’s fanciful, but not a fantasy. Like it’s soundtrack, there’s an almost jaunty feel to the movie. It’s a straightforward love story, a period piece set in Yokohama in 1963 – a simple film by Ghibli standards, more reminiscent of their earlier works than recent ones, more Takahata Isao than Miyazaki Hayao. It’s fascinating to speculate how much of the true spirit of the film is the manga, how much is the father’s screenplay, and how much the directorial vision of the son.

I wasn’t one of the many piling abuse on Gedo Senki, for the record – it was a flawed film, undeniably, but had some moments of true beauty (and as a huge fan of the books, I was a tough audience). But let there be no mistake, Kokuriku Zaka Kara is clearly better. It’s a Ghibli film through and through, but quite unlike any Hayao-sensei has directed in recent years. It’s fanciful, but not a fantasy. Like it’s soundtrack, there’s an almost jaunty feel to the movie. It’s a straightforward love story, a period piece set in Yokohama in 1963 – a simple film by Ghibli standards, more reminiscent of their earlier works than recent ones, more Takahata Isao than Miyazaki Hayao. It’s fascinating to speculate how much of the true spirit of the film is the manga, how much is the father’s screenplay, and how much the directorial vision of the son.

Matsuzaki Umi (Nagasawa Masami) is a high-school girl, living in the converted hospital that now serves as her family home and a boarding house. Her Grandmother is the dean of the household, Umi’s father having died during the Korean War when his supply ship hit a mine. Also living in the house is younger sister Sora (Shiraishi Haruka), a year behind Umi at school, and elementary student brother Riku (Kobayashi Tsubasa) as well as artist boarder Hiro (Hiiragi Rumi). Umi’s mother is a professor who appears to be rarely at home, traveling the world to further study her unidentified field (in America as the film opens).

Matsuzaki Umi (Nagasawa Masami) is a high-school girl, living in the converted hospital that now serves as her family home and a boarding house. Her Grandmother is the dean of the household, Umi’s father having died during the Korean War when his supply ship hit a mine. Also living in the house is younger sister Sora (Shiraishi Haruka), a year behind Umi at school, and elementary student brother Riku (Kobayashi Tsubasa) as well as artist boarder Hiro (Hiiragi Rumi). Umi’s mother is a professor who appears to be rarely at home, traveling the world to further study her unidentified field (in America as the film opens).

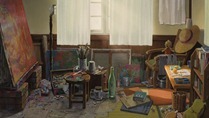

This big old house on the hill serves as the backdrop for much of the film, especially in the first half, as mature and responsible Umi’s daily life is portrayed in loving detail. She cooks, she fixes lunches for her siblings, and every day she raises signal flags as a gesture to her father to let him know she still remembers him. Nobody can do old house interiors like Ghibli, and their work is on fine display here – every nook and cranny is lovingly detailed in all it’s grubby beauty. But it’s at Konan Academy High School where much of the larger drama of the second half of the film takes place. Even more photogenic and quirky is the “Latin Quarter”, the ancient clubhouse that serves as a kind of asylum for the semi-wild boys of the school, who engage in all sorts of activities illicit and otherwise inside – and on the roof, and in the pond in front of the building – every activity but cleaning, it seems. It’s a spectacularly weird and delightful scene inside, but one could easily see why the resident girl population finds it rather scary.

This big old house on the hill serves as the backdrop for much of the film, especially in the first half, as mature and responsible Umi’s daily life is portrayed in loving detail. She cooks, she fixes lunches for her siblings, and every day she raises signal flags as a gesture to her father to let him know she still remembers him. Nobody can do old house interiors like Ghibli, and their work is on fine display here – every nook and cranny is lovingly detailed in all it’s grubby beauty. But it’s at Konan Academy High School where much of the larger drama of the second half of the film takes place. Even more photogenic and quirky is the “Latin Quarter”, the ancient clubhouse that serves as a kind of asylum for the semi-wild boys of the school, who engage in all sorts of activities illicit and otherwise inside – and on the roof, and in the pond in front of the building – every activity but cleaning, it seems. It’s a spectacularly weird and delightful scene inside, but one could easily see why the resident girl population finds it rather scary.

All that begins to change when Umi encounters Kazama Shun (Okada Junichi) as he’s diving into said pool from one of the gables (with mixed success). Shun-kun is the editor of the Latin Quarter’s rough but honest weekly newspaper, and the chief co-conspirator with Mizunuma Shirou (Kazama Shunsuke – an interesting coincidence of names, there) in a Quixotic campaign to keep the old building from being torn down to make way for a shiny new one. Japanese student activism in the 1960’s has been rather a hot topic in anime lately, it seems, and this is definitely a fairly innocent depiction of it – the students’ righteous anger is genuine, but there are no violent confrontations with police (or even police) here. As befits the overall tone of the movie, there’s more a feel of a wistful look back at the righteousness of youth (Hayao-sama’s influence might be at play here) than serious social commentary – though we do have full-throated railing against the “tyranny of the majority” and a society that “worships the future and forgets the past”.

All that begins to change when Umi encounters Kazama Shun (Okada Junichi) as he’s diving into said pool from one of the gables (with mixed success). Shun-kun is the editor of the Latin Quarter’s rough but honest weekly newspaper, and the chief co-conspirator with Mizunuma Shirou (Kazama Shunsuke – an interesting coincidence of names, there) in a Quixotic campaign to keep the old building from being torn down to make way for a shiny new one. Japanese student activism in the 1960’s has been rather a hot topic in anime lately, it seems, and this is definitely a fairly innocent depiction of it – the students’ righteous anger is genuine, but there are no violent confrontations with police (or even police) here. As befits the overall tone of the movie, there’s more a feel of a wistful look back at the righteousness of youth (Hayao-sama’s influence might be at play here) than serious social commentary – though we do have full-throated railing against the “tyranny of the majority” and a society that “worships the future and forgets the past”.

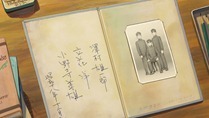

There are several different threads playing out in the film’s 90 minutes. There’s the matter of the students’ campaign to save the Latin Quarter, which leads them to Tokyo to appeal to the school’s Chairman (and alumnus) Tokumaru (Kagawa Teruyuki). Shun and Umi’s explorations of their sad and unusual family histories are a focus, and there’s the obvious love story. It becomes part of a somewhat tangled larger plot that’s probably more complicated than it needs to be, but the relationship between Shun and Umi itself works quite well – largely because both are refreshingly free of conventional anime stereotype. Umi is kind and a little naïve, Shun is just a bit impish and impulsive but thoroughly decent and direct, very much like his step-father.

There are several different threads playing out in the film’s 90 minutes. There’s the matter of the students’ campaign to save the Latin Quarter, which leads them to Tokyo to appeal to the school’s Chairman (and alumnus) Tokumaru (Kagawa Teruyuki). Shun and Umi’s explorations of their sad and unusual family histories are a focus, and there’s the obvious love story. It becomes part of a somewhat tangled larger plot that’s probably more complicated than it needs to be, but the relationship between Shun and Umi itself works quite well – largely because both are refreshingly free of conventional anime stereotype. Umi is kind and a little naïve, Shun is just a bit impish and impulsive but thoroughly decent and direct, very much like his step-father.

At heart, this movie is a period piece – the music, the look, the emotions all feel very much of the period. It’s nostalgic in a good way, fond without sugarcoating, and the small details – the streetcars, the old office buildings, the kitchen appliances, and especially the Latin Quarter (the scenes where the girls invade for a massive cleanup and redecoration – including the RCA dog in the foyer – are absolutely charming) are truly magical in that special Ghibli way. I quite liked the way class differences subtly intruded itself in the family dynamic as the past was explored by the kids. And while there’s plenty of drama here, it never reaches the level of melodrama – it all feels very everyday and grounded.

At heart, this movie is a period piece – the music, the look, the emotions all feel very much of the period. It’s nostalgic in a good way, fond without sugarcoating, and the small details – the streetcars, the old office buildings, the kitchen appliances, and especially the Latin Quarter (the scenes where the girls invade for a massive cleanup and redecoration – including the RCA dog in the foyer – are absolutely charming) are truly magical in that special Ghibli way. I quite liked the way class differences subtly intruded itself in the family dynamic as the past was explored by the kids. And while there’s plenty of drama here, it never reaches the level of melodrama – it all feels very everyday and grounded.

In summation, Kokuriko-zaka kara is a different sort of Ghibli film – different from what we’ve come to expect in recent years, anyway. It won’t rank among the very best of the studio’s impressive catalogue, but it’s both very good in its own right and fascinating as a measure of Miyazaki Gorou’s progress – and future – as a director. I see a young man developing a vision that’s different from his father’s – more puckish, modest and contemplative. It may be that “Takahata Oji-san” was more influential artistically on the boy than the father who was rarely home – that would be a fair guess based on “Poppy Hill”. Gorou-sensei may have no choice about being the next Miyazaki, but he doesn’t have to be The Next Miyazaki – he can find his own way, as Shinkai and Hosoda are doing, though it will be surely be more difficult in Gorou’s case. I think that’s the best thing for both Gorou-san and for Studio Ghibli, and based on Kokuriko Zaka Kara, there’s good reason to be optimistic about Ghibli’s future.

In summation, Kokuriko-zaka kara is a different sort of Ghibli film – different from what we’ve come to expect in recent years, anyway. It won’t rank among the very best of the studio’s impressive catalogue, but it’s both very good in its own right and fascinating as a measure of Miyazaki Gorou’s progress – and future – as a director. I see a young man developing a vision that’s different from his father’s – more puckish, modest and contemplative. It may be that “Takahata Oji-san” was more influential artistically on the boy than the father who was rarely home – that would be a fair guess based on “Poppy Hill”. Gorou-sensei may have no choice about being the next Miyazaki, but he doesn’t have to be The Next Miyazaki – he can find his own way, as Shinkai and Hosoda are doing, though it will be surely be more difficult in Gorou’s case. I think that’s the best thing for both Gorou-san and for Studio Ghibli, and based on Kokuriko Zaka Kara, there’s good reason to be optimistic about Ghibli’s future.

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

alualuna

June 21, 2012 at 9:05 am"I wasn’t one of the many piling abuse on Gedo Senki, for the record – it was a flawed film, undeniably" – I'm totally in agreement. I definitely think Gedo Senki wasn't as bad as many made it out to be, it had its moments even if there were flaws.

Also agree with you on Kokuriko Zaka Kara, which I was fortunate enough to see at the UK premiere in April. It is better and shows Gorou's potential as a director.

Antonio

November 28, 2012 at 12:29 pmGreat snapshots collection! particoularly the one with Sachiko and the kid!

I know there is a manga version of the movie, but i can't find it!

I just wonder if all these marginal charcters, like the PhD girl, are considered more!