Now that, dear readers, is an episode worth waiting for.

I’ve been generally in the defenders’ camp on Shoukoku no Altair, and I don’t regret it because it’s a series that’s deserved defending. The scores it receives on meta-review sites are in my view comically low, and many readers of the manga (which in fairness I am not) have been relentless in mocking and scorning it. But all along I was waiting for an episode like this one – one that would lift the series out of the realm of a good show worth defending and give it the air of the greatness I hoped it might achieve when I placed it at the top of my anticipation list for Summer 2017. One that would allow me, at long last, to embrace Shoukoku no Altair unreservedly.

I’ve been generally in the defenders’ camp on Shoukoku no Altair, and I don’t regret it because it’s a series that’s deserved defending. The scores it receives on meta-review sites are in my view comically low, and many readers of the manga (which in fairness I am not) have been relentless in mocking and scorning it. But all along I was waiting for an episode like this one – one that would lift the series out of the realm of a good show worth defending and give it the air of the greatness I hoped it might achieve when I placed it at the top of my anticipation list for Summer 2017. One that would allow me, at long last, to embrace Shoukoku no Altair unreservedly.

We’ve been building towards the denouement of the civil war arc for several eps now, obviously, as it represents the climax of the first cour for the anime (even if it technically falls in the second). What we got was truly splendid – not just a perfect conclusion to the political and military tangle of the sultanates’ rebellion, but a crystal-clear distillation of just how narrow the needle Mahmut is trying to thread here is. It’s (somewhat ironically) the ultra-calculating Ismail of Biçki that sums it up – Mahmut is a born battlefield commander trying to execute the ideals of a pacifist. And history shows us just how brutally difficult that is.

We’ve been building towards the denouement of the civil war arc for several eps now, obviously, as it represents the climax of the first cour for the anime (even if it technically falls in the second). What we got was truly splendid – not just a perfect conclusion to the political and military tangle of the sultanates’ rebellion, but a crystal-clear distillation of just how narrow the needle Mahmut is trying to thread here is. It’s (somewhat ironically) the ultra-calculating Ismail of Biçki that sums it up – Mahmut is a born battlefield commander trying to execute the ideals of a pacifist. And history shows us just how brutally difficult that is.

This was the achievement of this episode, in truth – not only did it give us a masterful plot resolution the likes of which Altair hadn’t yet delivered, but it also stamped Mahmut as the great protagonist a story like this needs in order to achieve transcendence. What Mahmut is trying to do is truly noble – to prevent a repeat of past tragedies in a world predicated on repeating them. It is indeed a game of thrones of the sort George Martin modeled his fictional setting after, albeit a bit further east. Mahmut is a good man, even if he is but a boy still – his naïveté of the first couple of arcs has evolved into a more hardened idealism, no less lofty in its aspirations but more tailored to harsh political reality.

This was the achievement of this episode, in truth – not only did it give us a masterful plot resolution the likes of which Altair hadn’t yet delivered, but it also stamped Mahmut as the great protagonist a story like this needs in order to achieve transcendence. What Mahmut is trying to do is truly noble – to prevent a repeat of past tragedies in a world predicated on repeating them. It is indeed a game of thrones of the sort George Martin modeled his fictional setting after, albeit a bit further east. Mahmut is a good man, even if he is but a boy still – his naïveté of the first couple of arcs has evolved into a more hardened idealism, no less lofty in its aspirations but more tailored to harsh political reality.

Worlds like this generally chew people like Mahmut up and spit them out, which makes the scope of what he’s trying to do that much more intimidating. But one advantage he has is that there’s a certain desire to follow people such as Mahmut when they prove they have the chops to back up their ideals – a recognition that such people are rare as hen’s teeth, and a simmering hope that if, somehow, they can overcome the massive odds against them they might actually make the world a better place. As Ismail tells Mahmut, soldiers don’t mind dying so much if they know what they’re dying for. The irony here (not lost on Mahmut) is that he’s exceptionally good at showing others what they’re dying for, even as he desires above all else to prevent their deaths.

Worlds like this generally chew people like Mahmut up and spit them out, which makes the scope of what he’s trying to do that much more intimidating. But one advantage he has is that there’s a certain desire to follow people such as Mahmut when they prove they have the chops to back up their ideals – a recognition that such people are rare as hen’s teeth, and a simmering hope that if, somehow, they can overcome the massive odds against them they might actually make the world a better place. As Ismail tells Mahmut, soldiers don’t mind dying so much if they know what they’re dying for. The irony here (not lost on Mahmut) is that he’s exceptionally good at showing others what they’re dying for, even as he desires above all else to prevent their deaths.

Mahmut shows off all his skills in the final resolution of the sultanates’ rebellion, starting with the military acumen that carries the battlefield (though without Beyazit’s muskets, it wouldn’t have been good enough). The real measure of Mahmut’s greatness is in the aftermath, however. Ismail has no qualms about killing his father – that’s the way of his family. But the matter of Fatma (Touma Yumi) is far more difficult. Sister of Balaban and Beyazit, mother of Aishe and the young prense Kemal, she’s the puppet sultan of Balta – ultimately forced to become a traitor in order to keep Kemal alive, manipulated by Balaban. Her fate – and that of her son – is the key question in the aftermath of the battle.

Mahmut shows off all his skills in the final resolution of the sultanates’ rebellion, starting with the military acumen that carries the battlefield (though without Beyazit’s muskets, it wouldn’t have been good enough). The real measure of Mahmut’s greatness is in the aftermath, however. Ismail has no qualms about killing his father – that’s the way of his family. But the matter of Fatma (Touma Yumi) is far more difficult. Sister of Balaban and Beyazit, mother of Aishe and the young prense Kemal, she’s the puppet sultan of Balta – ultimately forced to become a traitor in order to keep Kemal alive, manipulated by Balaban. Her fate – and that of her son – is the key question in the aftermath of the battle.

What Mahmut achieves here is a masterpiece of political acumen and wisdom, a Solomon-like end run around the impossible reality of the circumstances. Fatma must die – both Turkiye law and political reality demand it. Even Aishe acknowledges this – she knows what Ismail and Beyazit were willing to do in order to advance their goals. But Mahmut sees the big picture – he knows what the execution of his mother will do to Kemal and the prospects for unity among the four stratocracies in the future. In faking her execution and allowing Fatma to live in hiding Mahmut is taking an enormous risk – one few in his position would be willing to take. Perhaps it will in the end prove an unwise one. But what Mahmut hopes to achieve cannot be achieved without enormous risks – that’s why the odds are stacked so heavily against him. His willingness to take risks like this is proof of Mahmut’s potential for greatness.

What Mahmut achieves here is a masterpiece of political acumen and wisdom, a Solomon-like end run around the impossible reality of the circumstances. Fatma must die – both Turkiye law and political reality demand it. Even Aishe acknowledges this – she knows what Ismail and Beyazit were willing to do in order to advance their goals. But Mahmut sees the big picture – he knows what the execution of his mother will do to Kemal and the prospects for unity among the four stratocracies in the future. In faking her execution and allowing Fatma to live in hiding Mahmut is taking an enormous risk – one few in his position would be willing to take. Perhaps it will in the end prove an unwise one. But what Mahmut hopes to achieve cannot be achieved without enormous risks – that’s why the odds are stacked so heavily against him. His willingness to take risks like this is proof of Mahmut’s potential for greatness.

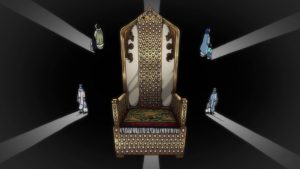

In truth, as I noted last week, these victories Mahmut and Zaganos are achieving are holding actions – even in “losing”, Louis is still advancing his cause and that of the Empire. He always initiates, and forces the enemy to respond. In order to turn the tables the Divan itself must take risks – and reinstating Mahmut as a pasha and giving him the new portfolio of Foreign Minister is such a risk. But this is what Mahmut was born for, it seems. As Zaganos notes, Mahmut is a “great orator” for whom it’s time to produce results (he certainly already has, but not on the scale now required). The strength of Mahmut’s oratory comes from the power of his character and convictions, and so does the loyalty of those who’ve chosen to follow him. It’s from such strength that historical greatness springs, and narrative greatness as well.

In truth, as I noted last week, these victories Mahmut and Zaganos are achieving are holding actions – even in “losing”, Louis is still advancing his cause and that of the Empire. He always initiates, and forces the enemy to respond. In order to turn the tables the Divan itself must take risks – and reinstating Mahmut as a pasha and giving him the new portfolio of Foreign Minister is such a risk. But this is what Mahmut was born for, it seems. As Zaganos notes, Mahmut is a “great orator” for whom it’s time to produce results (he certainly already has, but not on the scale now required). The strength of Mahmut’s oratory comes from the power of his character and convictions, and so does the loyalty of those who’ve chosen to follow him. It’s from such strength that historical greatness springs, and narrative greatness as well.

Earthlingzing

October 7, 2017 at 10:50 pmA great ending for a great arc. I’m glad that we’re getting another cour: after that, I don’t see much chance for a second season.

Guardian Enzo

October 7, 2017 at 10:57 pmMe neither, but two cours is twice what most series like this could hope for on their best day.